In striving to achieve valid teacher evaluations, schools often overlook those who spend the most time observing teachers in action: students. As the 2013 MET study reported, student surveys are a critical tool for effective teacher evaluation. By our calculations, a classroom of 30 students might clock about 27,000 hours observing a single teacher over a school year. It's no wonder students are more likely to arrive at a more accurate assessment than a single principal who reaches his or her conclusion on the basis of a few hours of observation.

New findings from a Dutch study not only reinforce these groundbreaking MET findings, but also add some intriguing nuance to our understanding of what students are able to discern about their teachers.

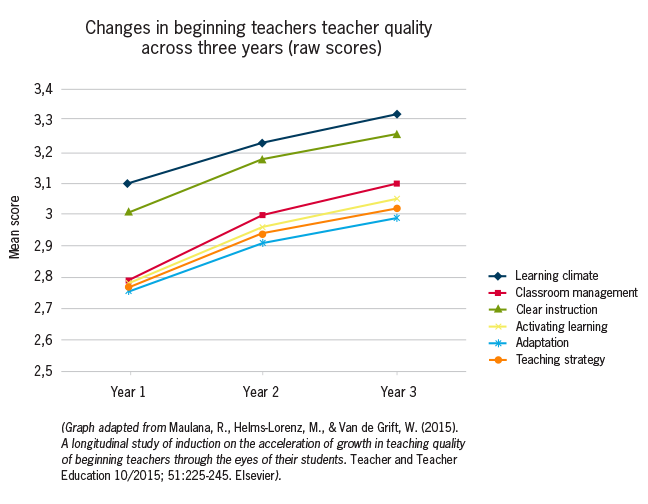

ome 5,000 students were asked how their teachers performed across six areas, including classroom management and clarity of instruction. Because students rated teachers over three years, their perception of a teacher's development from one year to the next could be captured. Adding even more evidence that student surveys are as accurate as any evaluation tool, they reached the same conclusion so many other kinds of research have consistently reported—that new teachers steeply improve for the first few years of teaching before leveling off.

The study also explores new territory. Because the sample of teachers included both teachers who had entered the classroom with formal preparation as well as those who had not, researchers probed to see if students could decipher any differences between the two groups. They could.

Across all areas, students gave consistently higher marks to teachers who had been formally trained than they did their walk-on counterparts. Given that most studies in the US have not been able to discern such differences (though no study that we know of has asked students to answer this question), this new finding suggests that either student surveys are more accurate than any measure that's previously been considered—or that the Dutch just do a better job of preparing teachers.

If the latter is the case, what might be the secret sauce of Dutch teacher prep? The central features of its preparation look like the American system—at least on the surface. New teachers must have demonstrated content proficiency in language and mathematics exams and have completed structured clinical practice, exactly the bones of what happens in the US. But in the Netherlands, practical experience is more extensive. Teacher candidates must complete 12 to 18 months of student teaching, typically in a school connected to the university.

In any case, the study builds the case for using student survey data in teacher evaluations, if not a closer examination of how the Dutch prepare their teachers.