Why is content knowledge important?

Content knowledge across an array of subjects and topics supports reading comprehension.

The full breadth of what teachers need to know and be able to do is expansive, and content knowledge is one of many critical requirements to be a successful elementary teacher, especially when teaching students to read. Much as learning phonics helps students decipher the sound of words, gaining background knowledge about a breadth of subject areas helps students draw meaning from what they read. A review of decades of research confirms:

"higher levels of background knowledge enable children to better comprehend a text. Readers who have a strong knowledge of a particular topic, both in terms of quantity and quality of knowledge, are more able to comprehend a text than a similarly cohesive text for which they lack background knowledge."20

Tests of students' reading comprehension reveal that their knowledge of the topic predicts their comprehension more accurately than their reading ability does.21 Moreover, spending more class time on social studies is associated with improved reading ability, especially for students who are learning English and for those who are living in poverty.22 Several studies of specific curricula or interventions have found building students' science and/or social studies content knowledge also supported their vocabulary and comprehension.23

A summary of research by Knowledge Matters highlights four ways in which background knowledge underpins reading comprehension:

"First, vocabulary tends to grow along with knowledge, but when just 2% of the words in a passage are not known, comprehension begins to drop.24 Second, the ability to process multiple details in a reading passage is severely restricted when readers aren't familiar with the topic(s) in the passage; cognitive scientist Daniel Willingham says that without adequate background knowledge, "chains of logic more than two or three steps long" can't be well comprehended.25 Third, when we know a little about a topic (e.g., that Alaska is freezing cold), we use that bit to generate a picture in our mind that helps us make sense of a related passage (e.g., that animals without heavy coats or other means of staying warm will struggle to survive in Alaska). Fourth, when we already know much of what's in a passage, we don't have to focus on its basics, and we can think critically: Does this passage make sense? Do I agree with its argument? How do the different items and ideas in this or several passages relate to each other?"26

Disparities in access to a broad curriculum reinforces inequities for students of color and students living in poverty.

Learning core content builds the foundation for later grades and supports students' ability to enter postsecondary education. In a recent report on educational equity, the National Academies of Sciences identified "disparities in curricular breadth," and in particular "availability and enrollment in coursework in the arts, social sciences, sciences, and technology," as a key indicator of educational inequities.27 Data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress and other sources confirms a sizable opportunity gap in core content areas for students of color and students living in poverty.28

Moreover, teachers with gaps in their content knowledge are more likely to work in more disadvantaged (and often lower-achieving) schools—those with higher rates of poverty and more students of color.29 Similarly, classes of students with higher prior achievement in math or in science are more likely to be taught by teachers who report higher levels of preparedness in those subjects, compared with classes of students with lower prior achievement.30

Inequities in early access to core content knowledge are cited as a key reason for later inequities in access to jobs,31 as disparities in access to jobs in the STEM field illustrate.32 Not only do students deserve to attain an education preparing them to pursue a variety of fields, but those fields benefit from the perspectives and participation of people from a broad range of backgrounds and experiences.33

Content knowledge is important for its own sake.

Learning about a new topic is an important and powerful experience in its own right. The National Academies of Sciences states,

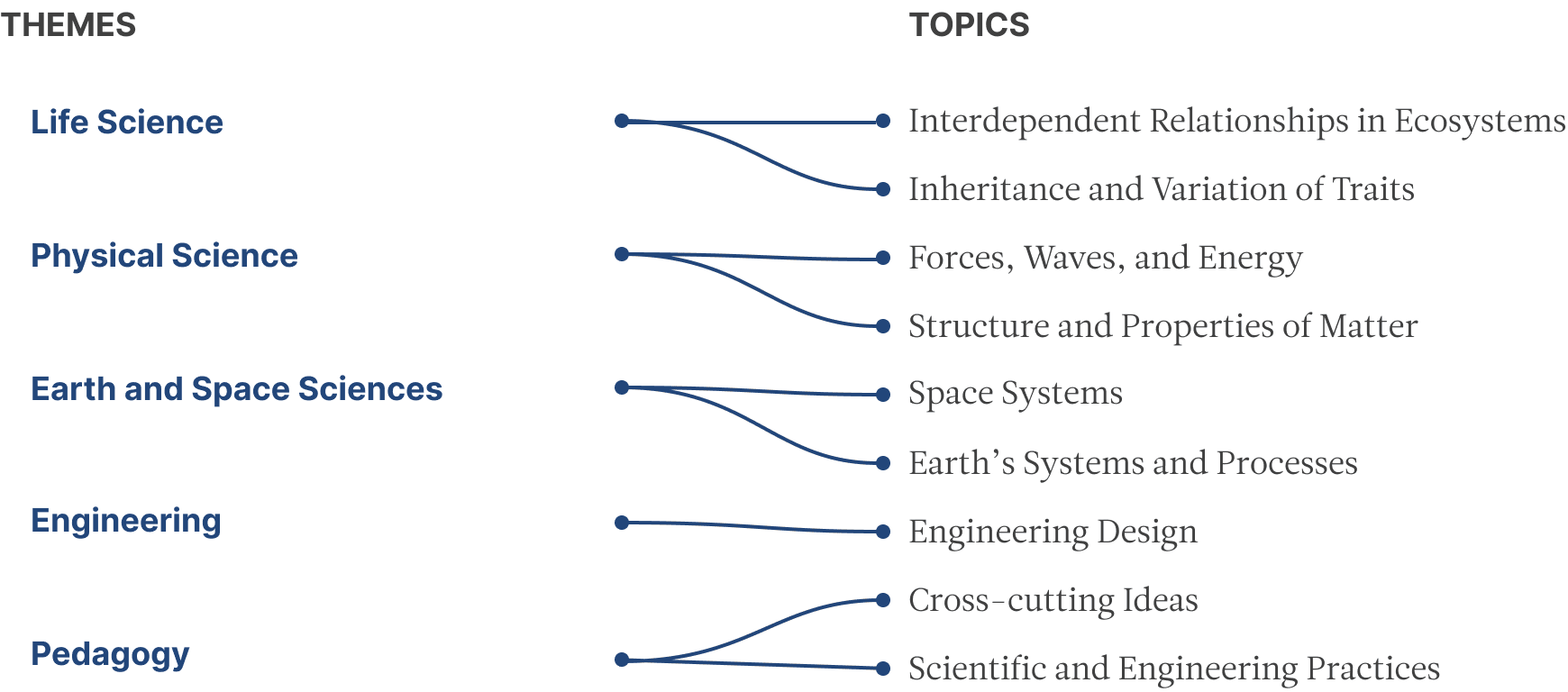

"Every child deserves to experience the wonder of science and the satisfaction of engineering. Children, even at very young ages, are deeply curious about the world around them and eager to investigate the many questions they have about their environment. Decades of research suggest that children are capable of learning sophisticated disciplinary concepts and can engage in scientific and engineering practices (National Research Council [NRC], 2007, 2012). Engaging them in learning science and engineering takes advantage of this interest and helps them to answer their own authentic questions and solve real-world problems that are important to them."34

Early exposure to science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) may have lifelong implications for students. Children form attitudes about STEM subjects in the early grades.35 Further, teaching children science concepts in the early grades establishes "the knowledge and skills they need to approach the more challenging science and engineering topics introduced in later grades."36 Experts also anticipate early exposure to STEM subjects increases students' interest in pursuing those careers.37

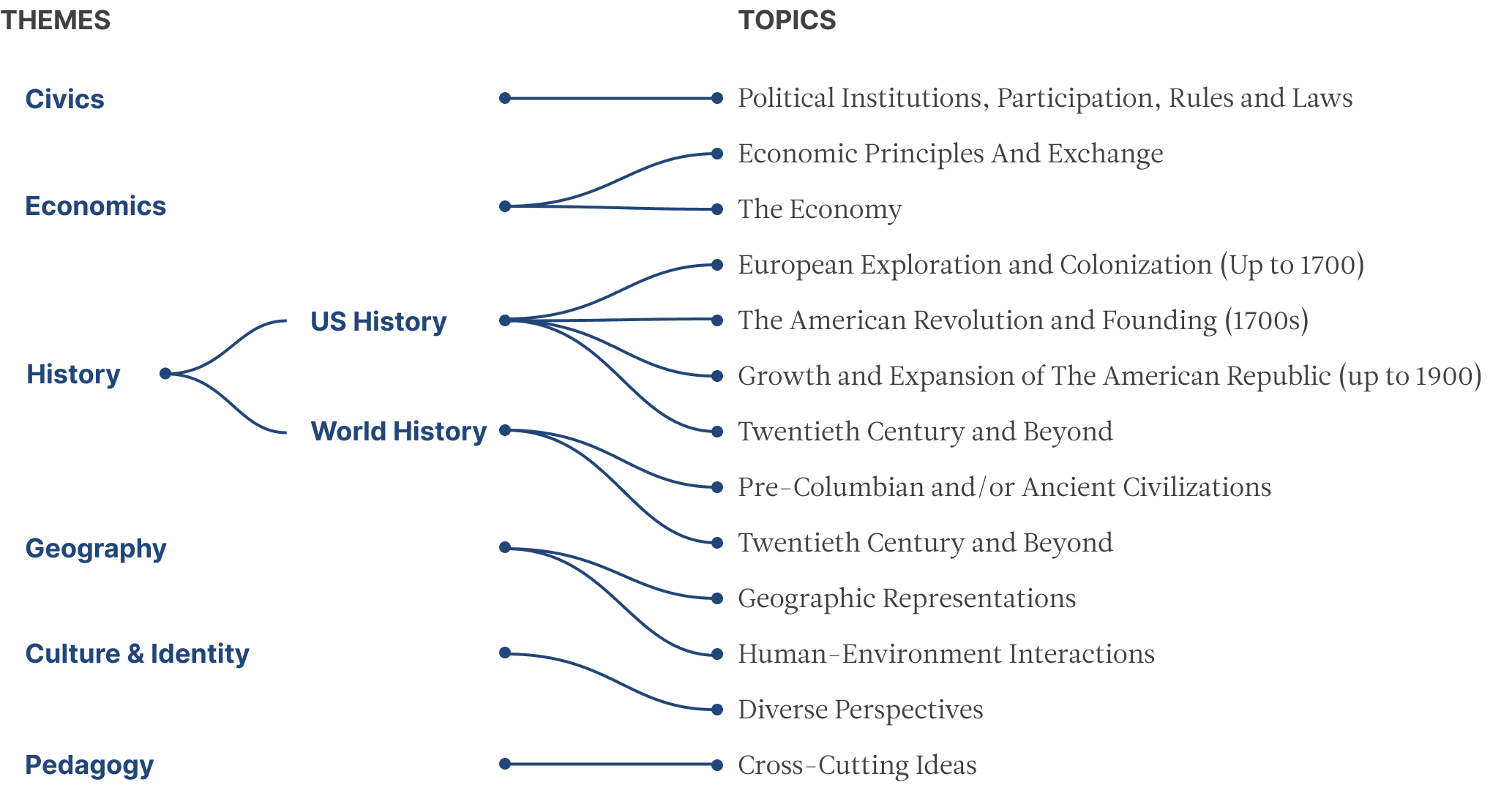

Regarding social studies, there have been several perspectives over the years on why elementary students should learn history and social studies. These include that students should learn social studies to promote "civic competence and a disposition toward participatory citizenship," and students should learn a more rigorous history curriculum because "study rooted in the disciplines not only teaches content more effectively but makes for more thoughtful and cognitively sophisticated students."38

Additionally, knowledge begets more knowledge. New research finds having prior knowledge of a subject makes it easier to acquire new knowledge on that subject.39 Learning about topics early on enables students to learn more content related to those topics faster, whereas students who miss an early introduction to a broad base of content will struggle to catch up.40 If the education system provides fewer opportunities to learn social studies and science to children from low-income backgrounds or children of color than their wealthier or whiter peers (which disparities in NAEP scores would suggest is the case41), this inequity not only leaves them on weaker footing in the elementary grades, but makes it harder for them to ever catch up.

Why do aspiring elementary teachers need dedicated content coursework as part of their preparation?

There is widespread agreement among the education field—teachers cannot teach what they do not know. A 2020 NCTQ survey found 83% of teacher preparation program leaders and 95% of state education agency (SEA) leaders agreed with this sentiment.42 The reasons these groups cited for the importance of content knowledge include:

Elementary teachers who have knowledge of a core content area can more efficiently plan lessons in that area (92% of teacher preparation program leaders and 93% of SEA leaders agree or strongly agree).

Teachers cannot know how to deliver instruction in a content area (pedagogical content knowledge) without first having a clear understanding of that content area (84% of teacher preparation program leaders and 90% of SEA leaders agree or strongly agree).

Elementary teachers need to have more advanced knowledge of content than what they teach their students (84% of teacher preparation program leaders and 95% of SEA leaders agree or strongly agree).

Elementary teachers who have knowledge of a core content area are more likely to effectively teach that content (87% of teacher preparation program leaders and 98% of SEA leaders agree or strongly agree).

Even though they have earned bachelor's degrees and sometimes master's degrees, many teachers enter the classroom without a clear foundation in the content they will be expected to teach. In a survey on behalf of the National Science Foundation, elementary teachers report they do not feel well prepared to teach science or social studies, and their reported rates of preparedness have declined in all subjects between 2012 and 2018.43 Federal surveys of new teachers (not specific to elementary grades) find only 37% report feeling very well prepared to teach their subject matter in their first year, and 31% feel they were very well prepared to meet state content standards in their first year of teaching.44 While teachers may not know everything they will be expected to teach before they set foot in the classroom, they will be far more effective if they enter with a foundation in most of the content knowledge.45

Further, this survey data is supported by a committee report from the National Academies, which concluded,

"The available evidence suggests that many science teachers have not had sufficiently rich experiences with the content relevant to the science courses they currently teach, let alone a substantially redesigned science curriculum. Very few teachers have experience with the science and engineering practices described in the [Next Generation Science Standards]. This situation is especially pronounced both for elementary school teachers and in schools that serve high percentages of low-income students, where teachers are often newer and less qualified."46

While research on teachers' elementary content preparation and knowledge is limited, most available research confirms a common sense conclusion—students learn more when their teachers know more. This relationship between the courses teachers take during their pre-service preparation or in-service professional development and their students' achievement has been found in English language arts and in science.47 Another study finds that when teachers learn more about an elementary mathematics topic during preparation, they address that topic more completely when teaching.48

Research generally finds the more a person knows about many different subject areas, the stronger his or her levels of literacy are, as measured by vocabulary and scores on tests of reading comprehension.49 A body of robust research spanning many decades connects a teacher's level of literacy or verbal ability and the achievement of that teacher's students.50

Elementary teachers' insufficient content knowledge may also impede their ability to give their students appropriate assignments. A 2018 TNTP study found "few…assignments gave [students] the chance to demonstrate grade-level mastery." In data TNTP shared with NCTQ for assignments from kindergarten through grade 5, only a quarter of English language arts assignments (28%) and half of math assignments (48%) were based on grade-level content.51 These results were particularly egregious for students of color: classrooms with mostly white students received 3.6 times more grade-appropriate lessons than classrooms with mostly students of color, and classrooms with mostly higher-income students received 5.4 times more grade-level lessons than classrooms with mostly low-income students.52

An insufficient background in core subjects may also hinder teachers' efforts to identify additional resources to use in their classrooms, or to assess the quality of those resources.53

When teachers have strong content knowledge in science and social studies, they are better prepared to help their students succeed in meeting the standards in those subjects and simultaneously better prepared to boost students' reading levels and literacy skills.