One feature of an ideal school environment, we

believe, is that both students and their teachers reflect America in all of its

diversity. Everyone, including children coming from privilege, benefits from a

diverse school experience.

It’s no wonder that as the minority student

population has grown in numbers in the past few decades, surpassing 50 percent,

so many of us are troubled that the minority teacher population has failed to

keep pace, standing now at only 18 percent minority. The push to achieve racial

parity between teachers and students has never been stronger, with urgent calls

from school boards, states, and even the U.S. Department of Education for the

nation to make teacher diversity a top goal for school districts.

This sentiment is understandable, commendable, but

— at the risk of being a wet blanket — not even remotely achievable within the

foreseeable future.

No matter how you run the numbers, school districts

simply cannot recruit and retain enough black and Hispanic teachers to achieve

racial parity between the teacher workforce and the U.S. student body – no

matter how many reprimands HR officials have to face from the their school

boards for the paltry results.

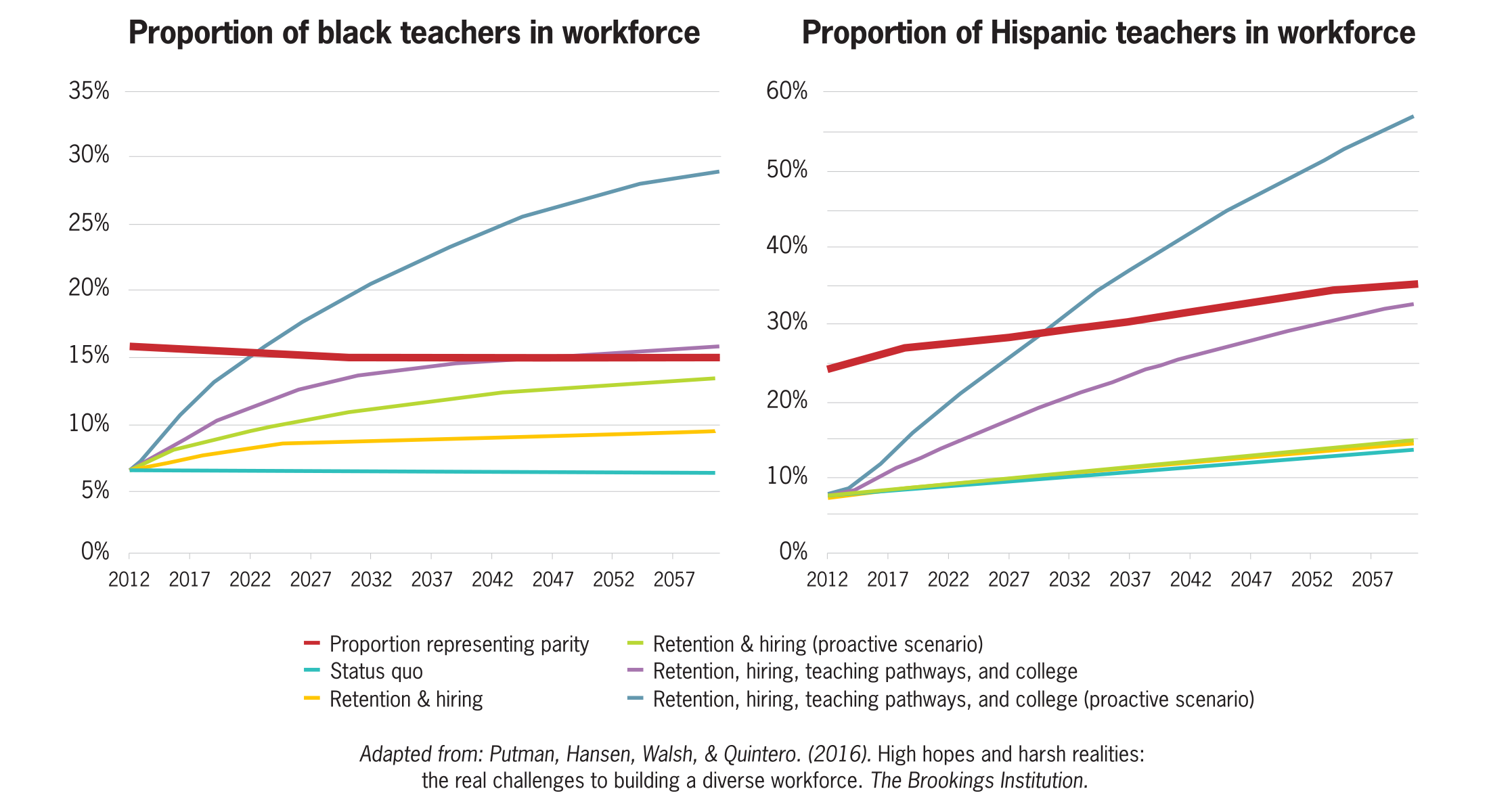

Researchers from NCTQ and The Brookings Institution

recently analyzed what it would take to create a teaching workforce as diverse

as the students it serves. You can find a full report of our analysis and

findings here.

We estimate the effects of different interventions

that might increase the number of minority teachers, extrapolating population

projections for the next four decades to see how close they can come to

creating a racially representative teacher workforce.

The findings are startling: parity or even

significant inroads to parity will remain completely elusive unless we fire on

all cylinders. If we can somehow boost the rates of college completion,

interest in teaching, hiring, and retention so that these rates for black and

Hispanic college students and adults mirror the rates of their white

counterparts, then parity becomes an achievable goal – but is still several

decades away.

How can this be?

Let’s walk through what we found, drawing on a

model we built using U.S. Census projections and data about the current teacher

and student populations to estimate the impact of various interventions.

For example, let’s see where a big push on

retention of black teachers gets us. Currently, 16 percent of America’s public school

students are black, compared to 7 percent of teachers, creating a nine

percentage point gap in the diversity of students and teachers.

What could happen if schools took real and

substantive steps to retain their black teachers so that year in and year out

black teachers stay in the classroom at the same rate as white teachers

(improving their current attrition rate from 10 percent to mirror white

teachers’ 7 percent)? We still wouldn’t close the diversity gap even projecting

out to 2060 (the furthest year of Census projections available).

Next, imagine we committed ourselves heart, body,

and soul (as many districts are, in fact, trying to do) to hire more black

teachers. The rewards would be tiny even projecting all the way out to 2060.

Okay, so what about persuading more black college

students to consider teaching? Higher education could heavily promote teaching

with undergraduates, or graduate programs and alternative providers could

recruit more black candidates—something that many claim to be doing already.

But let’s imagine pouring some real resources into these strategies, such as increased

salaries, loan forgiveness, or more leadership opportunities to succeed in

persuading black adults to consider teaching at the same rate as white adults (currently

4.3 percent of black undergraduate students major in education compared with

6.9 percent of white undergraduates; we see similar disparities for graduate

college education degrees and alternative certification enrollment).

Again, the results would be fairly paltry – closing

the diversity gap by about two and a half percentage points by 2060.

I’m guessing that a lot of people reading this are

thinking “but look at the success of Teach For America, now recruiting new

cohorts which are about 50 percent teachers of color?” TFA was able to achieve

these huge gains in part because it developed unprecedented recruitment efforts

of minority students beginning in their freshmen year—a great strategy to

emulate. But keep in mind that the corps is tiny compared to America’s needs.

Teach For America supplies less than 3 percent of the nation’s teachers. Its

hard push on this problem still only produced about 800 new black corps members

in a year. That’s enough to translate into significant gains for TFA, which is

only recruiting some 4,100 teachers in a year, but remains a far cry from the

300,000 more black teachers needed to achieve parity across all American

schools.

Let’s go back to the point of greatest disparity

between black and white students: the college completion rate. If we invest

heavily to support black students and ameliorate their low college completion

rate so that they graduate college at the same rate as white students

(currently 28 percent of black 22-year olds have earned a bachelor’s degree,

compared with 47 percent of white 22-year olds), we still will not come close

to closing the gap by 2060.

Disheartening, no?

For Hispanic teachers, the dismal scenario is much

the same. In fact because the Hispanic population in the US is growing at such

a fast rate, much faster than the black population, the diversity gap is

expected to widen if we do not take action.

Only if we are able to graduate more Hispanic

teachers from college or draw more Hispanic adults into careers in teaching can

we reduce the growing diversity gap significantly, otherwise expected to be 22 percentage

points by 2060.

Clearly, the answer is to combine all these

interventions and be successful at

all of them (success defined here as achieving the same rates as their white

counterparts) to make any real dent. If over the next decade we were to improve

college completion rates, interest in teaching, hiring, and retention to mirror

that of white teachers at every point, we would actually achieve parity by the

year 2044 for black teachers and students. The picture is less cheery for

Hispanic teachers, only coming within the ballpark (three percentage points

away from racial parity) by consistent pushes through 2060.

So are we

suggesting we all throw up our hands and give up on achieving greater parity?

Absolutely not. But let’s not underestimate the ambition, commitment, and

persistence needed, or browbeat school superintendents or human resources

officials when they are only able to make incremental progress. Let’s also not

advocate for racial parity at the expense of quality. The research is clear

that students’ success still depends most on the quality of their teachers

In the meantime, other important solutions can

achieve greater equity in our schools. Let’s look for meaningful ways to ensure

that teachers – who want to do right by their students – don’t unintentionally

do harm to the kids who don’t look like them. Let’s go beyond the stuff of

current trainings in which teachers and teacher candidates engage in a lot of

reflecting on their implicit biases, analyzing their white privilege, or

developing cultural sensitivity, much of which hasn’t had much impact –

although these do play an important role. Let’s do more to have teachers

examine their daily interactions with students by asking themselves: which

students do they call on to answer questions? Are some students more likely to receive

harsher disciplinary actions than others? Do they select some groups of students

for more challenging work over others? Give teachers the training and tools to

make sure that they do not allow their biases along race, gender, class, or any

other lines to get in the way of helping every child thrive.

More like this

What can California, Texas, and Washington, D.C. teach us about how to diversify the teacher workforce?

A New Roadmap for Strengthening Teacher Diversity

When “do no harm” is impossible, how can districts design teacher layoffs to do the least damage?