Those among us who invested a lot of time and energy to fix the staffing problems in the nation’s urban schools might feel a tad sheepish in the wake of a study of California’s schools. In groundbreaking work, we are dispelled of the long-held notion that urban and rural schools share roughly comparable challenges when it comes to their ability to recruit and retain teachers.

At least in California (though there’s no reason to think that the state is somehow unique), rural districts post 12 more vacancies for every 100 teachers than their urban counterparts. They also end up having to hire twice as many emergency certified teachers in their classrooms. And, in fact, urban schools look way more like the relatively stable suburban schools than most of us might have guessed, reporting only two more vacancies per 100 teachers than the nearby suburbs.

While both rural and urban schools have a more difficult time attracting teachers to their poorer schools, rural areas have higher poverty rates, as well as higher persistent child poverty. The Economic Research Services of the U.S. Department of Agriculture estimates that 524 out of the 664 counties suffering from extreme poverty in the nation are rural.

These high poverty rates explain only so much about the challenges rural schools face. Rural schools are more likely to be on or near a state border, cut off from many qualified teachers who, while living quite nearby, remain out of reach for the absence of valid licenses and lack of portability of their pension plans. So too are many rural schools located far from the nearest teacher prep program, depriving them of schools’ most reliable source of new teachers as programs are reluctant to place student teachers too far from campus.

Still, these three factors—higher poverty rates, closer proximity to a state border, and less access to student teachers—do not come close to explaining the severity of rural schools’ shortages. The “Starbucks” theory, with some research to substantiate it, is as good an explanation as any, meaning that the farther a school is from the nearest Starbucks, the more trouble it will have recruiting new teachers—a convenient metaphor for the lack of modern conveniences (many more significant than coffee).

While rural teacher salaries are quite a bit lower than urban salaries, these salaries appear generally commensurate with the cost of living and are not a worse financial deal for teachers. For example, rural schools in Kelseyville, California, pay 16% less than schools in San Francisco, but the cost of living is 36% lower, with similar figures reported elsewhere. Where salaries do fall short is that they likely need to be more than just comparable in order to convince teachers to give up urban conveniences.

All of this is to say that when we claim to tackle educational inequities, we cannot overlook the schools educating 20% of American students. To attract teachers to rural areas we either have to come up with a significant and steady infusion of cash—or life in rural America needs to become a more attractive proposition.

Could it be that Covid has done just that? The world today is substantially different than it was two years ago. Covid led to (or at least accelerated) significant major outward migration from some major metropolitan areas, notably San Francisco, Seattle, and New York, a signal that the commitment to cities is not unwavering when other options are available. This migration pattern may reverse itself, as was the case after the 1918 flu pandemic—but my wager is that it will not.

I’d argue that no previous event, no matter how similar, provides an apt comparison, because technology has changed everything, making it possible for the first time for workers to do their jobs from anywhere. But why, I expect you’re asking, would the ability to work remotely benefit rural schools, since teaching is not one of those jobs? Most teachers are married (or with a partner) and, presumably, most are part of a two-income earning family with one earner potentially working one of those more flexible jobs. Perhaps a circuitous solution to the problems that plague rural schools, it is one that could be beneficial nonetheless, even when workers relocate only as far as the outer suburbs. Even a moderate shift in work patterns could be a game changer for many rural schools.

Covid has also led some Americans to examine what constitutes ‘the good life.’ The number of Americans who express an interest in living in the country rose substantially from 38% in 2018 to 49% in 2020. The pandemic may have done rural schools a favor, reminding us of the inherent folly of Starbucks and perhaps other city amenities as well. After all, it is quite possible to make a good cup of coffee in the comfort of our own homes.

More like this

What we know (and don’t know) about pandemic-era teacher shortages

National jobs data suggests the wave of predicted teacher resignations has not come to pass.

What school districts can do to tackle teacher shortages

Coverage of teacher shortages tells of real struggles faced by districts, but it only tells part of the story.

Disproving the prophets of teacher shortages

Too often in education, education groups’ pursuit of validation for their policy priorities and the media’s desire for a strong narrative lead them to whip up a public frenzy at the expense of accuracy and nuance. That’s certainly what happened with states’ rapid retreat from testing as well as their sudden distaste for the Common Core standards. It’s why state legislatures continue to fight for class size reductions even though the adjustments are always too marginal to have any real impact on learning.

It’s also true when it comes to declarations of a national teacher shortage, claims that the media has bought hook, line, and sinker. Reporters continue to cite a 2016 report from the Learning Policy Institute (LPI) with the title, “A Coming Crisis in Teaching?” Its stark conclusion warned that the nation may face a 100,000+ plus annual teacher shortage by 2018. You may recall this troubling graphic:

Reprinted from Sutcher, L., Darling-Hammond, L., & Carver-Thomas, D. (2016). A coming crisis in teaching? Teacher supply, demand, and shortages in the U.S. Palo Alto, CA:Learning Policy Institute. page 2.

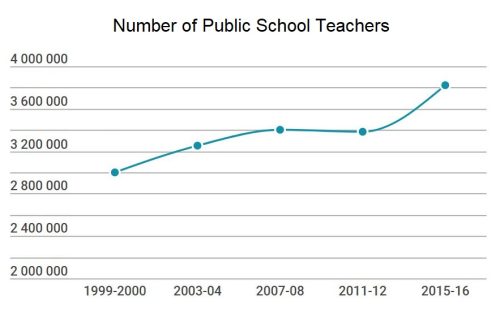

It’s almost 2018, folks and while LPI’s dire predictions rested on one set of assumptions, we now have actual data that showed that their projections were way off. The newest data out of NCES show that our public school teacher workforce is not shrinking but growing! In 2015-16, the estimated number of teachers reached over 3.8 million – an increase of about 400,000 in four years.

Moreover, based on 2015-16 projections, the number of students probably hasn’t grown nearly as fast as the number of teachers. Education Week reports, “The number of students went up about 2 percent over four years. And the number of teachers went up 13 percent during that same time.”

Check out this great graph from Education Week illustrating this change in population. It clearly shows a dip after the Great Recession, but since then, contrary to the fears of those claiming a nationwide teachers shortage, the teacher workforce has grown at a much faster rate than the student population.

Reprinted from Loewus, L. (2017). Teaching Force Growing Faster Than Student Enrollment Once Again. Education Week.

You can see our own depiction of growing teacher workforce below, using NCES’s data:

Of course, none of this is meant to deny the existence of severe shortages in some places or in some teaching areas. What it DOES mean is that, overall, there is not a new national teacher shortage. See our recent shortage fact sheet for more information.

We still don’t know why this increase has occurred. Possible explanations include that more people may be completing teacher preparation programs, that current teachers may be staying longer, that the student population may be growing, or that states are hiring more teachers through emergency certifications.

Unfortunately, one of the dangers of trying to solve the chronic misalignment of teacher supply and demand by erroneously labeling it a national teacher shortage is that the resulting remedies are all wrong. Of course, states and districts need to address their very real struggles recruiting teachers in some fields and localities. Still, in order to develop rational and effective solutions, leaders need a clear and accurate picture of the problem – and not a flawed, worst-case scenario.

For instance, districts may reject the idea of paying higher salaries to all teachers as unaffordable. But, they may be able to afford paying higher salaries specifically to teachers in shortage fields and location.

Similarly, states may react to the shortage mirage by authorizing poorly qualified emergency certified teachers, rather than improving reciprocity to make it easier for teachers to move into the state.

Teacher preparation programs, working on the assumption that a national shortage means plentiful job opportunities, may wind up preparing teachers for overpopulated fields like elementary education instead of recommending would-be teachers also obtain certification in special education or ESL.

So, the bottom line is, the teacher workforce has grown in the last few years. Now these researchers and analysts have a responsibility to acknowledge that their fears have not come true. Those who allow the media to perpetuate inaccurate stories are doing a disservice to school districts and their students across the country.

1. Data Sources: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Schools and Staffing Survey (SASS), “Table 209.20: Number, highest degree, and years of full-time teaching experience of teachers in public and private elementary and secondary schools, by selected teacher characteristics: Selected years, 1999-2000 through 2011-12.” Retrieved 25 August 2017 from: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d15/tables/dt15_209.20.asp. Taie, S., and Goldring, R. (2017). Characteristics of Public Elementary and Secondary School Teachers in the United States: Results From the 2015–16 National Teacher and Principal Survey First Look (NCES 2017-072). U.S. Department of Education. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved 25 August 2017 from https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2017072.