For many district leaders, concerns of teacher burnout in the wake of the pandemic remain paramount. Teachers are determined to make up instructional ground, but this sense of responsibility weighs heavily. In a nationally representative teacher survey, 47% of respondents indicated that supporting student learning because of the lost instructional time during the pandemic was the primary source of their job-related stress.1

To facilitate students’ pandemic recovery, teachers need not only instructional time but also planning time: time to review curricula and upcoming lessons, to evaluate students’ work and assess where students have grasped content and where they struggle, and to adjust future lessons accordingly. Setting aside time for teachers to do this work, both on their own and in collaboration with their peers, may support higher-quality instruction, with the important added benefit of reducing stress on teachers. Survey results from the past several years (and across a range of instruments) indicate that teachers consistently identify increased planning and collaboration time as one of the top features that would support teacher retention and job satisfaction:

- Nearly one in five Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) respondents in Educators for Excellence’s 2022 teacher survey identified “more collaboration and planning time” as one of the top two supports that would be most likely to keep teachers in the profession.2

- Teachers of color surveyed in the 2022 State of the American Teacher survey indicated “more time for collaboration with other teachers” as a key workplace practice that would be effective in retaining teachers of color.3

- Teachers selected “more planning time during the school day” as one of the main factors districts could take to help them most in their day-to-day teaching in a 2016 survey by the Center on Education Policy.4

- In a 2014 survey by Wood Communications Group, Wisconsin teachers indicated that more planning time “would have the greatest positive impact on [their] ability to help [their] students learn and realize their potential,” more so than more money or fewer disruptive students.5

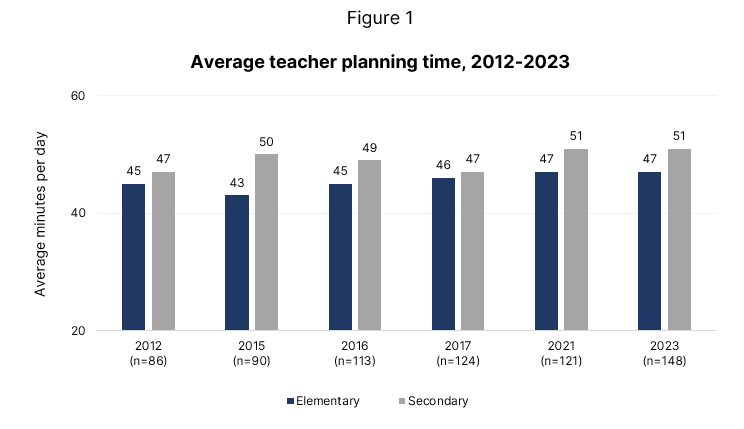

Given teachers’ interest in more planning and collaboration time, how are large districts across the U.S. responding? On average, large districts6 have not significantly increased planning time for teachers over the past several years (see Figure 1). In the more than ten years since NCTQ began collecting this data, the average amount of time teachers are guaranteed by their contract to plan and prepare has only increased by a few minutes.

| NOTE: The sample of districts has grown since NCTQ first began collecting data in 2012. This graph notes the differences in sample sizes. |

Average planning time

All teachers benefit from dedicated time reserved to plan lessons, reflect on their practice, collaborate with peers, seek guidance from mentors, and review student work, regardless of the grade they teach. Because many district contracts set different parameters for their elementary and secondary teachers, this analysis follows suit, examining planning and collaboration time in more detail—and by grade span—in the sections below.7

The average district in our sample affords elementary teachers about one class period per day (47 minutes) for lesson preparation and planning, roughly 10% of their scheduled workday (as outlined in their contract). Forty-three districts provide elementary teachers with planning time equivalent to a full class period or more (at least 50 minutes) each day.8 At the low end of the distribution, Long Beach Unified School District (CA) provides an average of only eight minutes per day for planning time, specified as 40 minute blocks scheduled 35 times per school year. On the high end, Aurora Public Schools (CO) requires 11 times as much: 90 minutes each day, in blocks of at least 30 minutes, to be reserved for teacher planning time.

For secondary teachers, it’s a similar story: large districts provide teachers with an average of 51 minutes per day for planning, and there is similarly wide variation across districts. Two districts in Georgia (Clayton County Public Schools and Atlanta Public Schools) give their secondary teachers the least amount of time among large districts, specifying that at least two hours per week (or 24 minutes per day, assuming the time is spread evenly over a five-day work week) must be held for teacher planning time. Teachers at the elementary level in these districts receive even less time—only one hour and 30 minutes per week (18 minutes per day). Fresno Unified School District (CA) provides the most planning time afforded to secondary teachers: 96 minutes per day, or an estimated 20% of the teacher’s scheduled workday.9

A handful of districts state in their governing policies that schools should provide their teachers with planning time, but do not specify the amount of time (10 districts at the elementary level; 12 at the secondary level), while some districts do not address planning time at all in their contract documents (19 districts at the elementary level; 26 at the secondary level).

It’s also important to consider the length of the contractually-determined workday. Differences in the total length of a workday mean planning blocks differ in the proportion of the day they represent, even if the time is the same. Such is the case in Lewisville Independent School District (TX), where a 45 minute planning block comprises 9% of an elementary teacher’s scheduled day, and in New Haven Public Schools (CT), the same 45 minute planning block comprises 11% of their day due to a shorter workday overall.

Two districts in our sample set policies that vary from school to school. In Minneapolis Public Schools (MN), teacher planning and collaboration time is determined at the school-level, where all licensed staff vote on how much planning time (and in how many blocks) they will be afforded for the following year, which must range between four hours and 35 minutes and nine hours and 10 minutes per week (or five-day cycle). A simple majority vote rules. In Pinellas County Schools (FL), teachers in high-need schools (determined by the grade the school earns from the state) receive additional time for collaborative planning, anywhere from 45-75 minutes per week.10 Those in the highest of needs schools are also allotted an additional 75 minutes of uninterrupted individual planning time. In all cases, these planning blocks are in addition to the base policy of 30 minutes daily (elementary-level) or one class period (secondary level) plus 2 hours per week outside the instructional day.

Differences in planning time, elementary vs. secondary teachers

Of the large districts that set clear parameters for planning time at both the elementary and secondary level (72% of our sample), 48 districts specify that all teachers, regardless of grade taught, have the same amount of planning time. Another 40 districts provide more planning time for their secondary teachers than elementary teachers. Such is the case in

San Bernardino City Unified School District (CA), where elementary teachers are afforded a minimum of 50 minutes per week of planning, while secondary teachers are afforded one class period (estimated 50 minutes) per day.11

In contrast, an estimated 18 districts allocate more time for their elementary teachers to plan than their secondary teachers.12 For example, Washoe County Public Schools (NV) elementary teachers receive 15 more minutes per day than secondary teachers (60 minutes vs. 45 minutes, respectively). In Seminole County Public Schools (FL), elementary teachers have two 40-minute planning blocks per day; one of which is designated as individual preparation time, the other is “devoted to Professional Learning Community (PLC) time, uninterrupted plan time, or tasks assigned by the principal or other administrators.”13 At the secondary level, Seminole County teachers are given one class period per day (or its weekly equivalent) with no additional time specified solely for collaboration or administrative items.

Collaboration time

In addition to independent planning time, teachers also benefit from opportunities to collaborate and calibrate with their colleagues. Sometimes referred to as “common planning time,” collaborative planning time provides time for teachers to share updates with each other about lessons and instruction, compare notes about how best to support specific students, ask questions of their peers, and collectively brainstorm solutions to challenges they are facing. This support makes a difference both in student learning and in building community among teachers and promoting connection and well-being.14

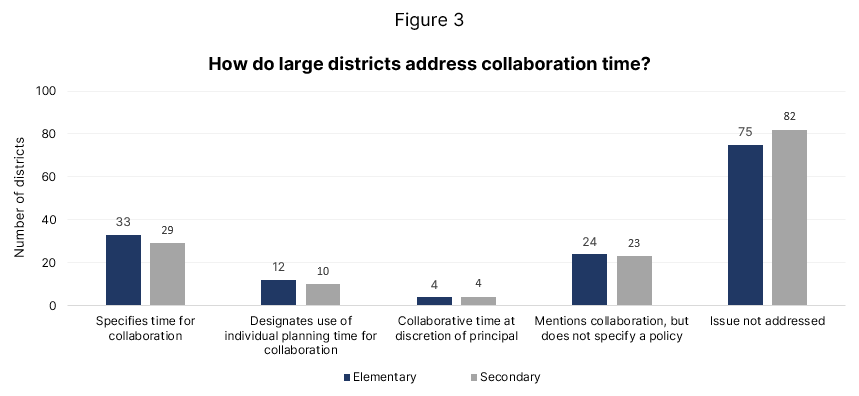

However, more than half of districts in this sample do not address collaboration time at all: 75 districts at the elementary level and 82 districts at the secondary level neglect to mention collaborative planning time. Of those that do lay out some type of specific guidance (33 districts at the elementary level, 29 at the secondary level15), the amount of time runs the gamut: while Cherry Creek School District (CO) affords elementary teachers one half-day per year, which may be used for “individual, team, or grade-level planning,” teachers in Wake County School District (NC) must meet with their Professional Learning Teams for a minimum of one hour per week.

Interestingly, districts are more likely to set a collaborative planning policy for their elementary teachers than their secondary teachers. In fact, 11 districts allocate time to collaborate with peers at the elementary level but not at the secondary level. For example, Boston Public Schools (MA) allocates a block of 48 minutes per week for elementary teachers, but does not specify a policy at the secondary level.16

Three of these 11 districts address collaborative time for their elementary teachers, though these policies are not specific or directive: both Detroit Public Schools Community District (MI) and Elk Grove Unified School District (CA) mention the use of collaborative planning time, but do not provide parameters, and Prince William County Public Schools (VA) states that the daily 45 minutes of planning time for elementary teachers is designated for both individual and team planning.

Another three school districts specify the opposite, reserving collaborative planning time to secondary teachers but not to elementary teachers. In

Pittsburgh Public Schools (PA), for instance, only secondary teachers participate in Teacher Interaction and Planning (TIP) time every Wednesday, while no policy is laid out for elementary teachers. The other two districts are Chicago Public Schools (IL), in which “three principal-directed periods per week may be used for [secondary] teacher collaboration…” and Burlington School District (VT), where secondary teachers have one hour per week for collaborative planning.

Considerations

Adjusting district planning and collaboration time policies will not be the panacea for all retention challenges. However, districts would do well to consider how planning and collaboration time might contribute to a larger array of teacher supports, and further, increase job satisfaction among teachers and enhance learning for students.17 Some questions district leaders can explore include:18

- What is the cost versus benefit? Finding the time—and money—to increase planning and collaboration time is no easy task. Weigh the benefits and limitations specific to your districts’ needs. If funds are particularly tight, are there creative solutions available to increase planning time but keep the cost down, such as leveraging non-instructional, “on-site” days for additional collaboration?

- Is there flexibility to rework the schedule? In designing the school day schedule, is it possible to give teachers of the same grades and/or subjects the same prep periods? District leaders interested in investigating this question may find Education Resource Strategies set of resources on the topic especially useful, including sample schedules and concrete strategies to incorporate sufficient collaboration time. A 2017 report from The Center for American Progress also highlights several additional innovative schedule options.

- Are teachers able to maximize their planning time? For example, is broken equipment, finicky or faulty technology, or stretched supplies chipping away at a teacher’s ability to make the most of their planning periods? Time spent hunting down supplies or fixing equipment is time that could otherwise be spent engaged in thoughtful planning. Though this may seem insignificant at first blush, the extra 10 minutes it may take to unjam a faulty printer, for example, is one-fifth of a typical daily planning period, which becomes a significant amount of lost time when issues like this are routine.

- How can district leaders promote investment among their principals and teachers to ensure collaborative planning time is productive? For all the evidence to suggest that collaborative planning and team time is a net positive, it can also run the risk of becoming overlooked or a “check-list” item, if it is not well-managed or lacks buy-in from both the principal and teachers. Harvard scholar Susan Moore Johnson finds that well-managed collaborative planning time requires mutual investment, a shared vision of purpose, and protection from interruption.19

More like this

A look back on how school districts are preparing for the years ahead

The most popular District Trendline posts of 2022, with topics ranging from pay increases for substitutes to building a positive school climate

It’s time to get serious about professional development and support for substitute teachers

It’s time to show our substitute teachers that we value them—and the time they spend with our students.

Supporting teachers through mentoring and collaboration

As school districts work out next year’s instructional format and take stock of their teacher workforce, districts in a position to hire are also readying themselves for a potentially unprepared influx of novice teachers.

Endnotes

- Steiner, E., Greer, L., Berdie, L., Schwartz, H., Woo, A., Doan, S., Lawrence, R., Wolfe, R., & Gittens, A. (2022). Restoring teacher and principal well-being is an essential step for rebuilding schools: Findings from the state of the American teacher and state of the American principal surveys. RAND Corporation.

- Educators for Excellence, Education Trust. (2022). Voices from the classroom: Deep dive BIPOC teachers.

- Steiner, E., Greer, L., Berdie, L., Schwartz, H., Woo, A., Doan, S., Lawrence, R., Wolfe, R., & Gittens, A. (2022). Prioritizing strategies to racially diversify the K–12 teacher workforce: Findings from the state of the American teacher and state of the American principal surveys. RAND Corporation.

- Rentner, D.S., Kober, N., & Frizzell, M. (2016). Listen to us: Teachers’ views and voices. Washington, DC: Center on Education Policy.

- Wood Communications Group. (2014). Business and education in Wisconsin: New expectations, needs, and visions are reshaping a vital, historic relationship.

- The sample for this analysis, drawn from NCTQ’s Teacher Contract Database, consists of 148 school districts in the United States: the 100 largest districts in the country, the largest district in each state, and the member districts of the Council of Great City Schools.

- The Teacher Contract Database (TCD) includes district collective bargaining agreements (CBAs), memorandums of understanding (MOUs), and Board policies. This sample is drawn from the TCD, and consists of 148 school districts in the United States: the 100 largest districts in the country, the largest district in each state, and the member districts of the Council of Great City Schools.

- For purposes of this analysis, a class period is assumed to be 50 minutes.

- Estimation from scheduled workday as specified in contracts.

- Schools receiving this additional time are those designated in Tiers II-IV by the state. For more information on how school tier designations are determined and how additional planning/collaboration time is afforded to teachers in these schools, see the district’s Designation of School Schedule document.

- Specifically, the San Bernardino City Unified School District reads that “[e]ach regular elementary school shall develop a schedule that provides a minimum of one thousand, seven hundred-twenty (1,720) minutes of preparation or conference time annually for each classroom teacher assigned to grades one through six (1-6) and all-day kindergarten. The schedule shall be developed as follows: 1. During each full week (Monday-Friday) throughout the year that has no holiday(s) scheduled, each teacher shall have no less than fifty (50) consecutive minutes of preparation or conference time, with the following exceptions…”

- Eleven of these 18 districts specify “one class period” is allocated for planning time at the secondary level. For the purposes of this analysis, NCTQ estimates “one class period” as 50 minutes. If a class period is longer, this could potentially equalize the amount of time between grade spans, removing the district from this count.

- Seminole County Public Schools, Teacher Contract: July 1, 2020 – June 30, 2023. p. 18, Art. X.F.1.a, b.

- Kraft, M., & Papay, J. (2014). Can Professional Environments in Schools Promote Teacher Development? Explaining Heterogeneity in Returns to Teaching Experience. Educational Effectiveness and Policy Analysis. 36(4). 476-500; Ronfeldt, R.; Owen Farmer, S., McQueen, K., & Grissom, J. (2015). Teacher collaboration in instructional teams and student achievement. American Educational Research Journal, 52(3), 475–514; Pil, F. K., & Leana, C. (2009). Applying organizational research to public school reform: The effects of teacher human and social capital on student performance. Academy of Management Journal (52), 1101-1124.

- This count includes districts that set a policy that specifies a clear amount of time and cadence. Districts where teachers can use their own planning time, collaborative planning is at the discretion of the principal, or collaborative planning time is vaguely mentioned are not included in this count.

- However, Boston Public School’s MOA does address planning time for special education teachers, noting that “[i]f practicable in the school schedule, teachers who meet the requirements for student IEPs, using both a general education or ESL license and a special education license will be afforded one additional 48-minute period per week for special education paperwork.”

- See: David Schleifer, D.; Rinehart, C. & Yanisch, T. (2017). Teacher collaboration in perspective: A guide to research. Spencer Foundation and Public Agenda. Retrieved from http://www.in-perspective.org/pages/teacher-collaboration

- Considerations 1-3 adapted from Moore Johnson, S. (2019). Where teachers thrive: Organizing schools for success. Harvard Education Press.

- As discussed in Heller R. (2020). Organizing schools so teachers can succeed: A conversation with Susan Moore Johnson. Phi Delta Kappan International. Retrieved Dec. 15, 2022 from https://kappanonline.org/organizing-schools-so-teachers-can-succeed-a-conversation-with-susan-moore-johnson/.