Earlier

this month, NCTQ released its biennial State

of the States report, which looks

at national trends in teacher effectiveness policies, including a close look at

state

teacher evaluation systems. The report highlights the importance of policies

connecting evidence of teacher effectiveness to other key personnel policies. This

month, the Trendline takes a

look at the role of student growth in evaluation ratings and how districts

connect evaluation ratings with compensation and dismissal policies.

Student growth

in evaluations

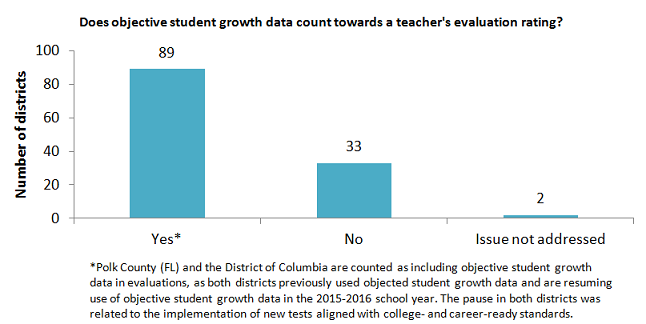

Two

years ago, 65 districts in the Teacher

Contract Database required student growth, measured by standardized test

scores, to be factored into teacher evaluation ratings. By the 2014-2015 school

year, 89 districts now require the use of objective student growth data, and another

16 districts plan to include some objective measure of student growth in

teacher evaluations in future years.

Of course, much of teacher evaluation policy is driven by the state. Since 35 states now require student growth to be a preponderant or significant criterion in teacher evaluations, it follows that the majority of districts in the database (68 percent) reflect this growing national trend in teacher evaluations.

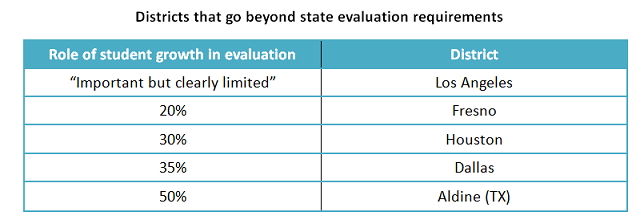

Of

note, however, are five districts that recognize the importance of objective

student growth data, even though state law does not. Neither California nor

Texas currently requires the use of student growth in teacher evaluations.[1]

Two California districts, Fresno and Los Angeles, both give

nods to student growth in their evaluation systems. Aldine, Dallas and Houston, all located in Texas, have already

implemented evaluations requiring the use of student growth that go above and

beyond the state’s future requirement for counting objective student growth

data for a recommended 20 percent of the evaluation in the 2016-2017 school

year.

Compensation

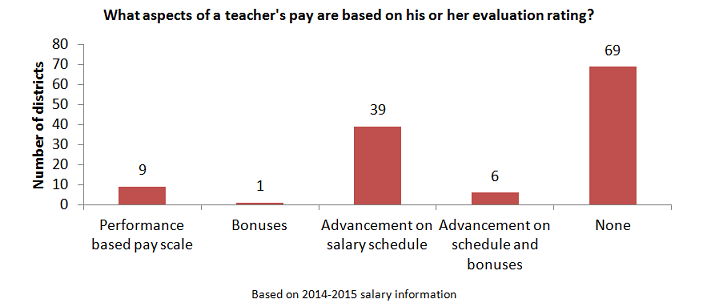

There

has been a significant amount of movement by districts to connect pay to teachers’

evaluation ratings. The last time we looked at this

topic in 2013, only 28 percent of districts in the database connected a

teacher’s evaluation to pay; in 2014-2015, 44 percent of districts connect the

two in some way. Interestingly, we find that this is an area where districts

seem to be outpacing the requirements of state law: about one quarter of the

districts in the database (30 districts), base some aspect of teacher pay on individual

evaluation ratings even though they are located in states that do not require

it.

Traditionally,

teachers are paid according to a salary schedule that determines pay based on

education level and years of teaching experience. The majority of districts (46

of 55) that connect teacher pay with evaluation ratings maintain a traditional

salary schedule, but require that teachers have a satisfactory evaluation in

order to move along the salary schedule. Of these 46 districts, six (Caddo Parish, the District of Columbia, East Baton Rouge, Fort Wayne, Newark and New Orleans) also offer bonuses to teachers, ranging

from $250 in Caddo Parish to $20,000

in the District of Columbia. In

2014-2015, Atlanta offered bonuses to teachers based on

evaluation ratings.

In

2013, only Harrison (CO) had a non-traditional salary

system, solely based on performance instead of years of experience, education

and other factors. Now, an additional eight districts have also moved to non-traditional

salary systems. In accordance with Florida state law, Brevard County, Broward County, Lee County, Orange County and Palm Beach County have all

adopted performance pay systems where a teacher’s salary base and salary

increases are based on his or her evaluation rating.

Although

Colorado does not require districts to implement performance pay systems, three

other Colorado districts, in addition to Harrison,

have also adopted non-traditional salary systems. Like Harrison, Douglas County and Jefferson County give salary increases solely based on

a teacher’s performance. Douglas County also offers additional bonus

pay to teachers with the highest levels of performance. Teachers in Denver receive salary increases based on a

variety of factors including student growth, evaluation ratings, professional

development (including base salary increases for advanced degrees) and market

incentives based on placements in hard-to-serve schools and hard-to-staff

assignments.

Dismissal

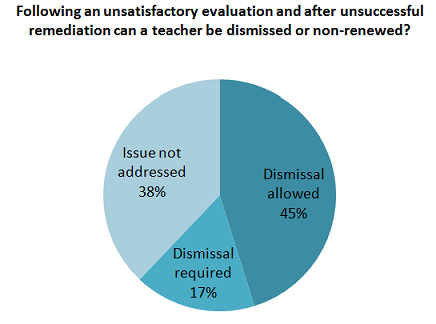

Just

under two-thirds of districts connect poor evaluations to dismissal. Generally,

after a teacher receives an unsatisfactory final evaluation, he or she is

placed on a remediation plan. In 45 percent of districts, if a teacher has

failed to improve at the end of the remediation plan, the teacher may face

dismissal. Dismissal is required in 17 percent of districts, most of which (17

of 21) are located in states that make a connection between an unsatisfactory

evaluation and eligibility for dismissal. Mobile, St. Paul, Davis (UT) and the District of Columbia all have policies requiring dismissal if a

teacher has failed to improve after remediation.

It’s

clear from this month’s analysis that when it comes to evaluation and

dismissal, districts mostly appear to follow the states’ lead. But when it

comes to compensation, some districts are taking the first steps to update

traditional salary systems in the absence of state requirements. For more

details on district evaluation policies, read an earlier Teacher

Trendline

on the topic.

To learn more about the trends in state policies, check out NCTQ’s most recent

release, the State of the States 2015.

[1] While including student growth in evaluations is not

part of Texas state law, the state does have an ESEA waiver issued by the

federal government. Under this waiver, the state is piloting evaluations where

growth will count for 20 percent of teacher ratings. It is scheduled for full

implementation in 2016-17. However, in October 2015, Texas was placed on

“high-risk status” by the U.S. Department of Education because the state still

does not require every school district to use student growth data in

evaluations.

More like this

Beyond one-size-fits-all: The case for differentiated teacher compensation

Research that moved minds: Top Teacher Quality Bulletin articles of 2024

When “do no harm” is impossible, how can districts design teacher layoffs to do the least damage?