March 2015: Teacher evaluations

District Trendline, previously known as Teacher Trendline, provides actionable research to improve district personnel policies that will strengthen the teacher workforce. Want evidence-based guidance on policies and practices that will enhance your ability to recruit, develop, and retain great teachers delivered right to your inbox each month? Subscribe here.

For this month’s Trendline, we closely examine teacher evaluation policies in the largest

districts across the country. Specifically, we take a look at the major

components within evaluations, frequency and teachers’ ability to grieve their evaluation

ratings.

Evaluation components

Evidence of student growth

or achievement

Perhaps the most debated

component of teacher evaluations is whether to factor in any evidence of

student learning based on objective student achievement data. The vast majority

of districts, approximately 72 percent, use some kind of measure of student growth

or student achievement data in some part to determine a teacher’s evaluation

rating.

While most of the districts

in our database do include evidence of student learning within teacher

evaluations, it’s important to note that they do so in a variety of ways, not

just through value-added measures. Most districts measure student learning

through various measures, like scores on standardized assessments, student

learning objectives (SLOs) and other growth goals.

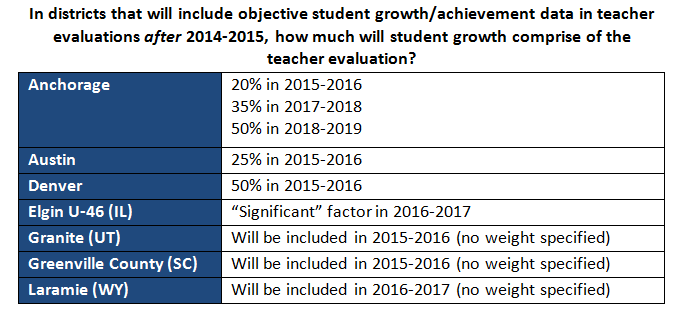

Over a quarter of large

districts in the Teacher Contract Database (28 percent) still do not include such measures in

teacher evaluations, despite a flurry of state and federal policies the past

few years moving districts in this direction. This number should come down in a

few years as a number of districts have explicitly stated this year that they plan

to include such data in teacher evaluations in future years: Anchorage, Austin, Denver, Elgin U-46

(IL), Granite (UT), Greenville

County (SC) and Laramie (WY).

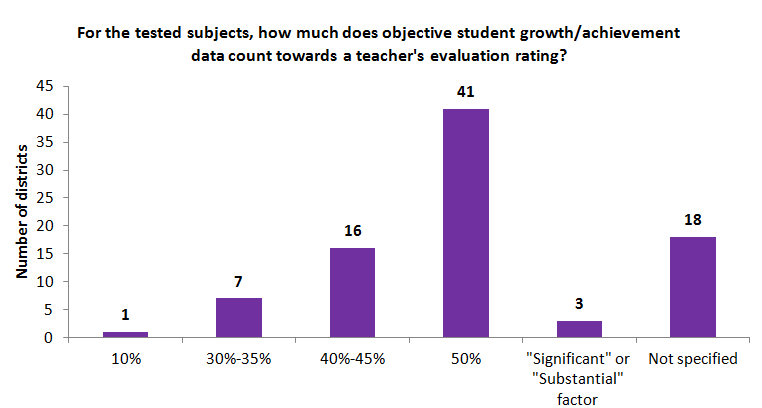

While 86 districts currently

include student growth or achievement data in teacher evaluations, these

districts do not all incorporate this measure in the same way. Nearly half (48

percent) have established that 50 percent of the overall evaluation is measured

by student growth/achievement data for tested subjects (usually math and

reading). Another 21 percent of these districts do not give a specific weight

to how much student growth/achievement data will count in the total evaluation.

How are districts dealing

with teachers in non-tested subjects? When we take a look at whether or not

student growth/achievement is considered in teacher evaluations for teachers in

non-tested subjects, we find that 75 percent of large districts do use

objective measures of student learning in evaluations assessing teachers of

non-tested subjects.

Peer review and student

input

When it comes to other

components of teacher evaluations—peer review and student input—we find more

variety in how districts do or don’t incorporate these measures.

With peer review and student

input, many districts make it a choice individual schools can choose to

include.

Peer review, however, is a

much more widely used measure in teacher evaluations than student input. Almost

half of our districts either require peer review or allow it as an option. Just

a third of districts require or allow student input.

Evaluation frequency

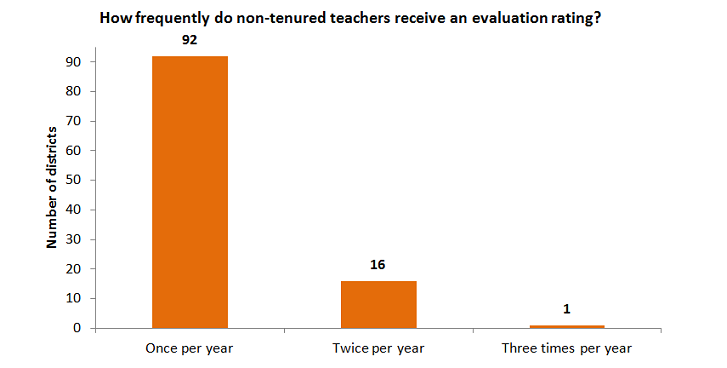

In the vast majority of

districts, nearly 77 percent, non-tenured or beginning teachers are evaluated

once per year. One district—Clark County

(NV)—is an outlier, formally

evaluating non-tenured teachers three times per year.

Eleven

districts are not included in the chart above, including six Florida districts

(Broward

County, Lee County, Miami-Dade, Palm Beach, Pinellas

County and Polk County) and Oakland, where teachers in their first year are evaluated two

times per year and annually thereafter. In Orange

County (FL), the district

evaluates beginning teachers even more frequently, with evaluations twice a

year for teachers in their first through third years of teaching, and annual

evaluations thereafter.

Columbus

(OH), Greenville

County (SC) and St. Paul also have distinctive evaluation policies. In Columbus, first-year teachers are

evaluated once. Thereafter, the frequency

of their evaluation is based on their performance. In Greenville,

first-year teachers receive only informal feedback about their practice and are

not formally evaluated. In St. Paul,

first-year teachers are evaluated three times per year; second- and third-year

teachers are evaluated twice per year.

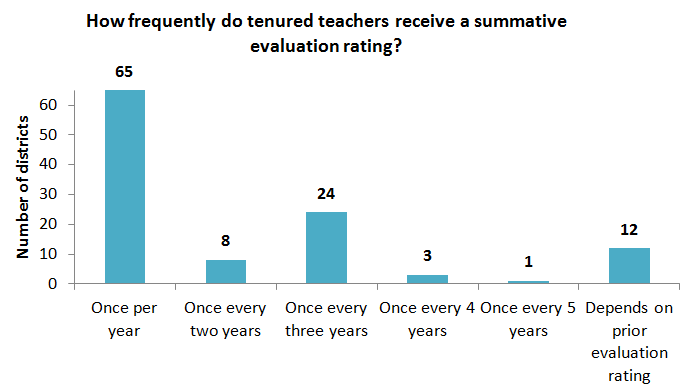

While

non-tenured or beginning teachers tend to be evaluated more frequently, tenured

teachers are almost always evaluated less frequently.

While over half of the

districts evaluate tenured teachers annually, nearly a quarter of districts (23

percent) formally evaluate teachers at most once every three years.

Not included above are five California districts, (Fresno, Long Beach, Los Angeles, Sacramento and San Diego), where teachers are initially evaluated once every

two years, until they gain 10 years of experience, after which they are

evaluated only once every five years.

Grievances

After the evaluation rating

is assigned, teachers can, in some districts, grieve the rating under certain

circumstances even if there are no previous procedural violations in how the

evaluation was carried out.

Over two-thirds of large districts

(42 districts) allow teachers to grieve or formally appeal their evaluation

rating even if there are no procedural violations that took place. Of those

districts, seven (Billings

(MT), Los Angeles, Milwaukee, Montgomery

County (MD), Polk County (FL), Prince

William County (VA) and Richmond

(VA)) only allow a formal appeal

or grievance to be filed if the teacher in question received one of the lowest

evaluation ratings.

From just last year, we’ve

found districts have changed or clarified many aspects of their evaluation

systems and in the years ahead, we expect this trend to continue; so check back

on our Teacher Trendline often to read about those changes, or run your own

report on teacher evaluation policies in the Teacher Contract Database to see for yourself.

More like this

Districts are facing hard choices: How can teacher evaluation help?

Rural teacher evaluation system shows promising results for students struggling in math

Put me in, coach! How practice plus coaching helps aspiring teachers win