Just as you wouldn’t start a marathon without taking practice runs, new teachers shouldn’t become teachers of record without getting experience in the classroom first. Clinical practice offers that training experience, allowing aspiring teachers to build their skills with real students, under the coaching of an expert cooperating teacher. New teachers report that clinical practice (also known as student teaching) was the most important part of their teacher prep.1 And a growing body of research shows that some aspects of clinical practice, like the instructional effectiveness of the cooperating teacher, make a huge difference in how effective new teachers are. Yet NCTQ’s past work has found that the field hasn’t caught up with the research. We set out to discover why, surveying hundreds of people from teacher prep programs and school districts.2

In this District Trendline, we share what we learned about what’s going well and what’s been challenging in building a strong clinical practice experience, as well as which policies and supports could lead to better experiences.

What are the strengths and weaknesses?

Overall, we found little alignment between responses from prep programs and districts. Generally, prep programs tend to identify strengths at a much higher rate than districts do, and districts’ top three strengths were all related to the quality of the cooperating teachers they employ.3

Strengths, as viewed by:

| Prep programs | Districts4 |

| Alignment in subject area to what student teachers will likely teach (79%) |

Effectiveness of cooperating teachers at establishing a positive classroom environment (40%) |

| Number of different placements (71%) | Instructional effectiveness of cooperating teachers (38%) |

| Categories to provide feedback on observation instruments (70%) | Effectiveness of cooperating teachers at mentoring adults (38%) |

| Alignment in grade level to what student teachers will likely teach (69%) | Alignment in grade level to what student teachers will likely teach (37%) |

Areas for improvement, as viewed by:

| Prep programs | Districts5 |

| Diversity of cooperating teachers (14%) | Ensuring student teachers are culturally competent (28%) |

| Focus on classroom management (10%) | Range of experiences in schools with different socioeconomic statuses or resources (28%) |

| Range of experiences in schools with different socioeconomic statuses or resources (7%) | Alignment in subject area to what student teachers will teach (27%) |

| Effectiveness of cooperating teachers at mentoring adults (7%) | Alignment in socioeconomic status to where student teachers will teach (27%) |

Takeaway: School districts and prep programs need to open the lines of communication so that they can share what’s working well and what needs to change. These two organizations are supposed to be working toward a common goal, yet their responses were considerably different.

Cooperating teachers

Learning from an expert helps aspiring teachers become more expert themselves. Several studies have found that having a highly effective cooperating teacher6 (as measured by their effect on student learning) can help a first-year teacher become as effective as one in their second or third year.7

The good news is that both school districts and prep programs agree that the quality of the cooperating teacher matters quite a lot. Districts and prep programs both identified the following facets of cooperating teachers as the three most important: their effectiveness at mentoring adults, their effectiveness at establishing a positive classroom environment, and their instructional effectiveness.

Yet identifying effective teachers to serve as cooperating teachers is also seen as a top challenge. Two-thirds of prep programs (64%) identify this as one of the greatest challenges they face.

Notably, prep programs and districts both say that they require cooperating teachers to be instructionally effective, which differs markedly from other evidence about this practice. NCTQ’s

2020 review of about 1,200 prep programs found that only 10% of prep programs take an active role in screening for any cooperating teacher skills or qualifications. Further, a study from Washington State found that two out of five cooperatin teachers in the state were less effective than the average teacher (while there were many more effective teachers in the state who could have hosted student teachers).8

Takeaway: Both districts and prep programs agree that cooperating teachers should be effective instructors—but they face challenges in identifying and recruiting them. To increase student teachers’ access to the strongest cooperating teachers, districts and prep programs should work together to share information and identify opportunities for funding cooperating teachers and student teachers.

Stipends for cooperating teachers and student teachers

Hosting a student teacher requires additional time spent mentoring them—and potentially additional stress as a novice teacher runs their classroom (though, fortunately, research shows students’ learning shouldn’t suffer if the cooperating teacher is effective9). For student teachers, working in a classroom full time (plus preparing in their off hours and potentially attending concurrent courses) requires a tremendous investment of time and may preclude them from holding a paid job. For these reasons, compensating both cooperating teachers and student teachers not only recognizes their time and effort, but it may also make these roles more attractive and financially feasible, especially for aspiring teachers of color, who take on more student loan debt.10

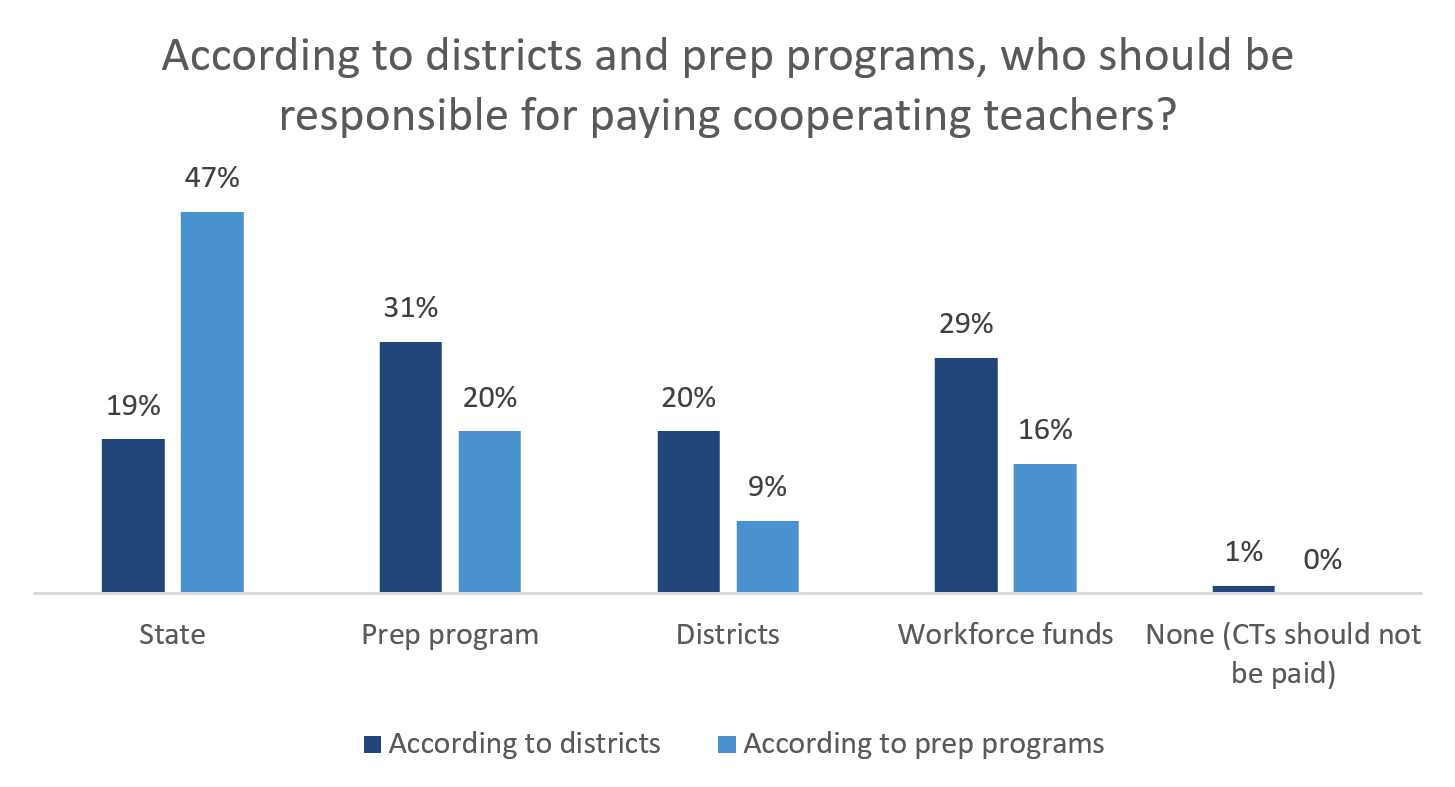

Notably, districts and prep programs differ in their views on who should pay cooperating teachers. Surprisingly, districts were more likely than prep programs to think that the districts themselves should provide this compensation.

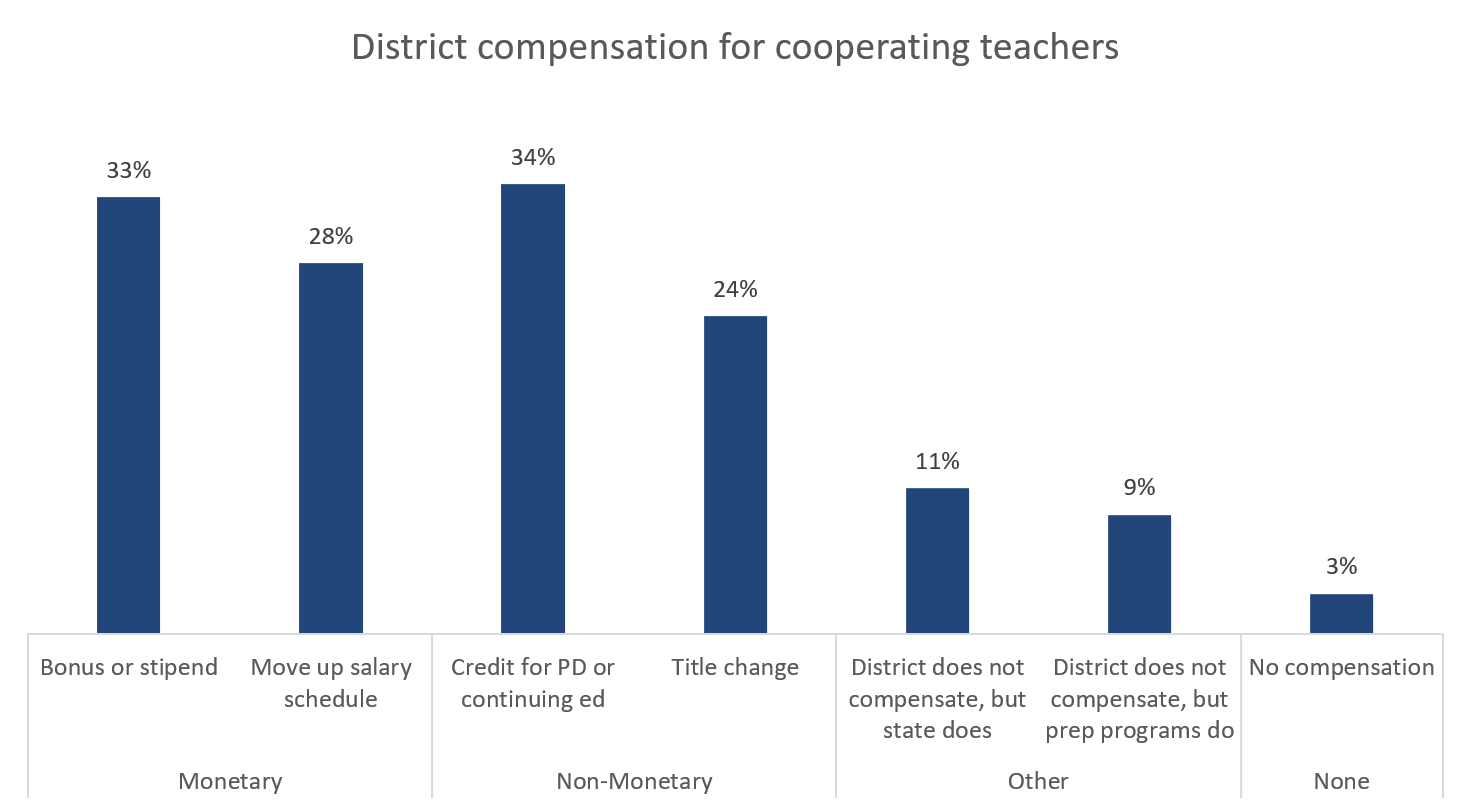

Two-thirds of districts report offering some kind of compensation to their cooperating teachers (37% offer monetary compensation, 37% offer non-monetary compensation, and 18% offer both).

Among teacher prep programs, 80% report providing some kind of compensation to cooperating teachers, most often monetary compensation (71%). This payment amount averages about $218 per semester,11 and ranges from $30 (in the form of an Amazon gift card) to $2,000 (time period not specified). Some prep programs also offer free access to coursework.

When asked how much cooperating teachers should be paid,12 prep programs’ responses averaged about $1,080 per semester, ranging from $100 to $6,000. Districts thought that cooperating teachers should be paid an average of $2,730, ranging from $10 to roughly $40,000.

Note: Workforce funds are typically regional or state funding allocated to build the state’s workforce.

Note: Workforce funds are typically regional or state funding allocated to build the state’s workforce.

Respondents also shared interest in providing stipends or other funding to student teachers. More than half of prep programs identified making clinical practice financially feasible for student teachers as one of their greatest challenges, and identified this as the top support they would like from their states and high on their list of supports to receive from districts. More than half of districts said that providing stipends to student teachers was very or moderately feasible, and a slightly greater share thought it would be feasible to allow student teachers to work (e.g., as a substitute or paraprofessional) while student teaching.

Takeaways: Compensation may help with recruiting cooperating teachers and student teachers, and prep programs and districts should actively reach out to multiple sources (including the state) to provide that funding. Respondents also suggested that it would go a long way if districts could find the funding to pay for student teachers.

Aligned settings

Research has found that student teaching in schools with more positive school climates, and specifically lower teacher turnover, is associated with better outcomes,13 as is student teaching in classrooms that are demographically similar to where they’re likely to get their first job.14 Since novice teachers are disproportionately hired into schools with more students of color and more students living in poverty,15 preparing in similar schools could give them an important advantage when they start teaching. When student teachers work in schools serving historically marginalized students, it is that much more imperative that they work alongside highly effective cooperating teachers so that aspiring teachers’ learning does not come at a cost to their students. In fact, research finds that student learning does not suffer when hosting student teachers, so long as the cooperating teachers are themselves effective.16

Respondents indicate that considering classroom demographics is not high on their list of priorities when arranging student teaching placements. Among prep programs, about half (58%) consider school characteristics (e.g., teacher retention, student demographics) when placing student teachers, 80% consider school climate, and 48% consider alignment with the socioeconomic status of student teachers’ likely first job. Among districts, 32% consider which schools have a positive climate when placing student teachers.

Takeaways: Prep programs, ideally with the help of their state’s data systems, should identify the characteristics of schools where their teachers tend to find teaching jobs and work with districts to place student teachers in similar settings with support and careful selection of the cooperating teachers.

Considering hiring needs when placing student teachers

Surprisingly, considering upcoming hiring needs ranks low for both prep programs and districts. Clinical practice allows school districts to get a head start on hiring (and hiring sooner leads to better outcomes!17). This approach gives hiring principals an opportunity to observe and test candidates before they apply for jobs in their schools. Teachers are more likely to get a job near their student teacher placement than they are to get a job near their hometown,18 and districts that host student teachers are less likely to need to hire emergency-certified teachers.19

Only 23% of prep programs consider which districts are likely to be hiring in the coming year when determining clinical practice placements. Of prep programs that do consider hiring needs, many report that their information comes from conversations with district leaders, though a few look at job postings or vacancy data.

When placing student teachers, only 31% of school districts consider the grades in which they anticipate having job openings, 31% consider subjects with anticipated openings, and 30% consider schools with anticipated openings.

More promising is that nearly all districts (96%) have a process in place to vet and hire student teachers into teaching positions. And based on survey responses, virtually every district that hosted student teachers hires at least some of them in an average year.

Given that many districts report staffing shortages, and that teachers are likely to take jobs near where they student taught, aligning student teaching placements with anticipated hiring needs could create benefits for both student teachers (who will soon need jobs) and districts (which need to staff their classrooms). In fact, 37% of districts think they could do a better job of identifying future hiring needs.

Takeaway: Future hiring needs should be a key consideration when placing student teachers. Districts need to better track and communicate anticipated hiring needs to prep programs, and prep programs need to factor in upcoming vacancies when identifying districts in which to place student teachers.

Tracking the outcomes

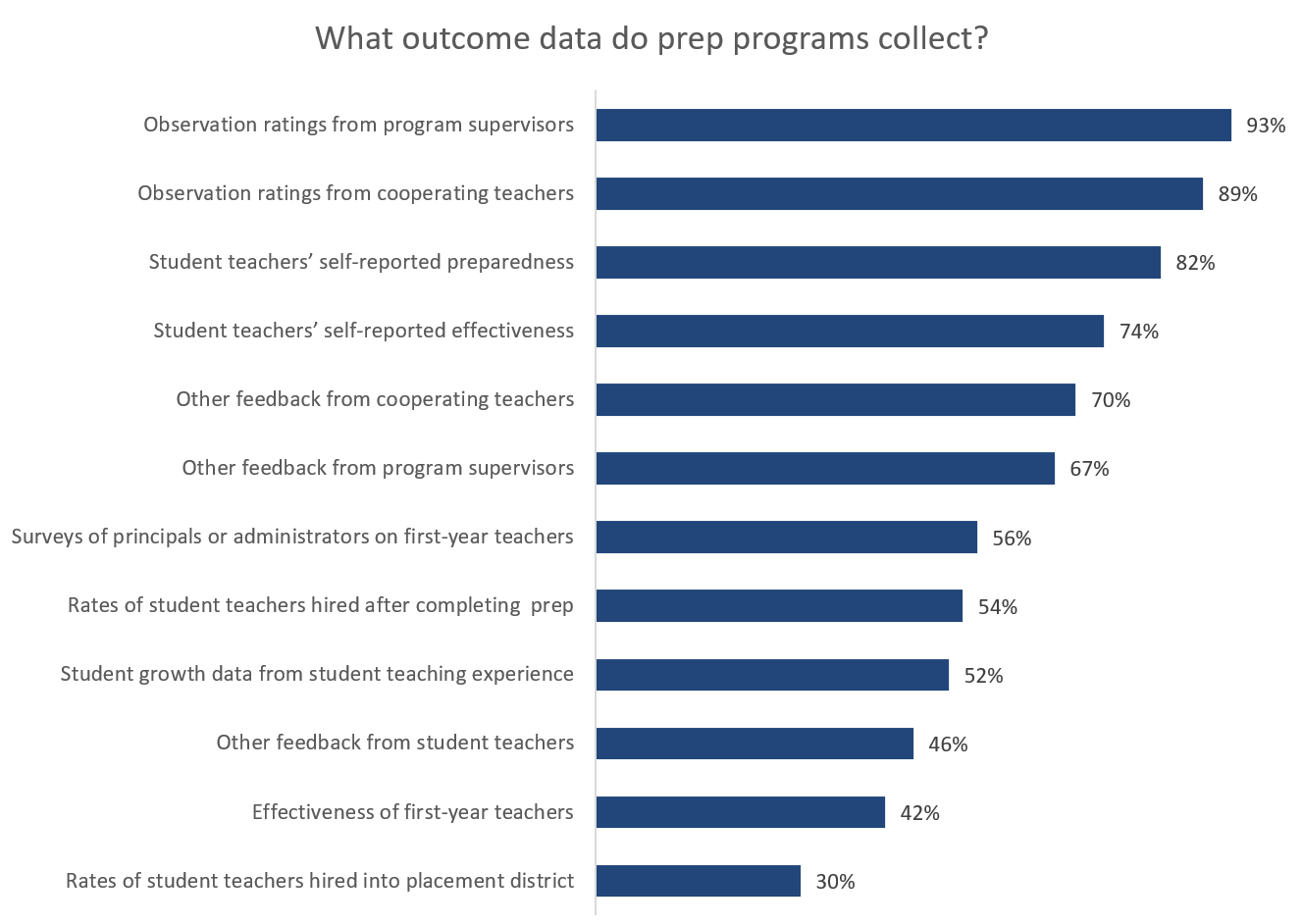

To improve upon something, one must first know what’s working well and what isn’t. Generally, prep programs report that they track data on clinical practice, but their emphasis is on data collected during clinical practice and less so on outcomes after student teachers have finished preparation. For example, almost all prep programs (93%) report gathering feedback from student teachers, most commonly via surveys.

Prep programs also gather several other sources of data on student teachers’ outcomes:

Takeaways: Prep programs are tracking data that is more readily accessible to them (e.g., observation ratings during student teaching, student teachers’ self-reports), but collaboration with districts (facilitated by a state longitudinal data system) would help them collect longer-term data like rates of student teachers who are hired (and where) and their effectiveness in the classroom.

What’s happening in districts that don’t host student teachers?

Most districts (84%) host student teachers every year, but a sizable minority of districts (16%) rarely, if ever, hosts student teachers—though nearly half of them (40%) would like to host student teachers more often. The top challenges getting in their way are:

- lack of housing and transportation for student teachers (49%)

- lack of available cooperating teachers (42%)

- lack of time and resources to oversee clinical practice (36%)

Districts seeking to increase the number of student teachers they host or improve the quality of the clinical practice experiences they provide are looking to their states and prep program partners for help. They would most like their state to set clear requirements for student teachers (e.g., requirements around passing licensure tests) and set guidelines for the types of activities student teachers should do during their placement. Districts would also like the opportunity to provide feedback to prep programs about student teachers’ strengths and weaknesses.

Who completed the survey

Of the 144 prep program respondents to the survey, nearly all (97%) were in institutions of higher education.

- The majority were in public institutions, though nearly a third were in private not-for-profit institutions, and a small share were in private for-profit institutions or non-institution-based alternative route programs.

- Half of the programs were in cities, 20% in the suburbs, 20% in rural areas, and 11% in towns. None were virtual.

- Forty-one states were represented.

Of the 721 respondents to the district survey, nearly half were from traditional public school districts, a third were from public charter districts, and a fifth were from private schools.

- The districts were divided fairly evenly between very large (more than 25,000 students), large (10,000–24,999 students), somewhat large (5,000–9,999 students), and medium (2,500–4,999 students), with fewer small or very small districts.

- District responses represented a mix of city (17%), suburban (24%), town (19%), rural (17%), and virtual (2%).

- Respondents hailed from 49 states and DC (Vermont was the lone state without respondents).

Stay tuned for more on clinical practice!

An effective clinical practice program sets novice teachers—and their first class of students—up for success when they have a classroom of their own. Establishing strong clinical practice programs requires a combined and concerted effort from teacher prep programs, school districts, and their states.

In a forthcoming

Clinical Practice Framework (March 2024), NCTQ will delineate the actions that each of the three core actors (teacher prep programs, districts, and states) should take to develop strong clinical practice experiences.

This summer, NCTQ will release a

Clinical Practice Best Practices Guide, spotlighting prep programs, districts, and states from across the country that have established strong clinical practice opportunities.

Have a best practice you’d like to share? Reach out to Hannah Putman,

hputman@nctq.org.

More like this

Scrambling to hire teachers doesn’t have to be a recurring rat race

Filling those hard-to-staff teacher vacancies doesn’t have to be so hard. Making a few straightforward adjustments to compensation, incentives, and partnerships can change the game.

Six steps to hire a strong teacher workforce

Insights on what school districts can do to ensure every classroom is staffed with an effective teacher.

If you want to help new teachers improve, invest in great coaches

People have life coaches, nutrition coaches, and executive coaches. So, it’s no surprise to see schools turning to coaches as well.

Endnotes

- Levine, A. (2006). Educating school teachers. Education Schools Project; Guyton, E., & McIntyre, D. J. (1990). Student teaching and school experiences. In W. R. Houston (Ed.), Handbook of research on teacher education (pp. 514–534). Macmillan; Brimfield, R., & Leonard, R. (1983). The student teaching experience: A time to consolidate one’s perceptions. College Student Journal, 17, 401–406.

- The surveys were fielded in fall 2023 and received 144 responses from teacher prep programs and 721 responses from school districts.

- For each component, respondents could code whether it was a strength, about average, or an area for improvement.

- Districts included here are those that regularly host student teachers.

- Districts included here are those that regularly host student teachers.

- Cooperating teachers are veteran teachers who host student teachers in their classrooms, also known as mentor teachers.

- Goldhaber, D., Krieg, J., & Theobald, R. (2020). Effective like me? Does having a more productive mentor improve the productivity of mentees? Labour Economics, 63, 101792.

- Goldhaber, D., Krieg, J., Naito, N., & Theobald, R. (2020). Making the most of student teaching: The importance of mentors and scope for change. Education Finance and Policy, 15(3), 581–591.

- Ronfeldt, M., Bardelli, E., Brockman, S. L., & Mullman, H. (2020). Will mentoring a student teacher harm my evaluation scores? Effects of serving as a cooperating teacher on evaluation metrics. American Educational Research Journal, 57(3), 1392–1437; Goldhaber, D., Krieg, J., & Theobald, R. (2018). The costs of mentorship? Exploring student teaching placements and their impact on student achievement. Working Paper 187. National Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research (CALDER).

- Carver-Thomas, D. (2018). Diversifying the teaching profession through high-retention pathways. Learning Policy Institute.

- NCTQ calculated payment by semester, assuming 16 weeks per semester. If the timeframe for payment was not specified, we assumed it was by semester.

- Notably, some responses identified recommended payment per student teacher hosted, suggesting that it is common for a cooperating teacher to host multiple student teachers in a semester. Note that when respondents provided a range, we used the mid-point of the range. When respondents indicated “at least,” we used the low point provided. When respondents did not indicate a time period, we assumed numbers provided were for one semester.

- Goldhaber, D., Krieg, J., & Theobald, R. (2014). Knocking on the door to the teaching profession? Modeling the entry of prospective teachers into the workforce. Economics of Education Review, 43, 106–124.; Ronfeldt, M. (2012). Where should student teachers learn to teach? Effects of field placement school characteristics on teacher retention and effectiveness. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 34(1), 3–26.

- Goldhaber, D., Krieg, J. M., & Theobald, R. (2017). Does the match matter? Exploring whether student teaching experiences affect teacher effectiveness. American Educational Research Journal, 54(2), 325–359; Krieg, J. M., Goldhaber, D., & Theobald, R. (2022). Disconnected development? The importance of specific human capital in the transition from student teaching to the classroom. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 44(1), 29–49.

- Goldhaber, D., Quince, V., & Theobald, R. (2018a). Has it always been this way? Tracing the evolution of teacher quality gaps in US public schools. American Educational Research Journal, 55(1), 171–201; Goldhaber, D., Lavery, L., & Theobald, R. (2015). Uneven playing field? Assessing the teacher quality gap between advantaged and disadvantaged students. Educational Researcher, 44(5), 293–307.

- Goldhaber, D., Krieg, J., & Theobald, R. (2018). The costs of mentorship? Exploring student teaching placements and their impact on student achievement. Working Paper 187. National Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research (CALDER).

- James, J., Kraft, M. A., & Papay, J. P. (2023). Local supply, temporal dynamics, and unrealized potential in teacher hiring. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 42(4), 1010–1044.

- Krieg, J. M., Theobald, R., & Goldhaber, D. (2016). A foot in the door: Exploring the role of student teaching assignments in teachers’ initial job placements. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 38(2), 364–388.

- Goldhaber, D., Krieg, J., Naito, N., & Theobald, R. (2021). Student teaching and the geography of teacher shortages. Educational Researcher, 50(3), 165–175.