The 2019-2020 school year is coming to a close, but school district leaders will continue to face the challenges of distance learning as they plan for both summer school and fall openings.

When the pandemic first hit, NCTQ took an initial look at a sample of 41 large school districts across the country to see if their collective bargaining agreements or school board policies contained any language relevant to what we are now experiencing, particularly in regards to teacher work, pay, and leave when schools are closed for any kind of extended emergency. We subsequently investigated how these large districts were dealing with teacher evaluations, with opportunities for classroom observation infeasible and most state student assessments cancelled.

Since these initial analyses, we have updated our sample to now include 74 of the largest school districts in the country (which includes the largest district in each state) and have analyzed the data based on districts’ continued teacher policy responses to the crisis.

What existing policies did districts already have in place to deal with emergency closures?

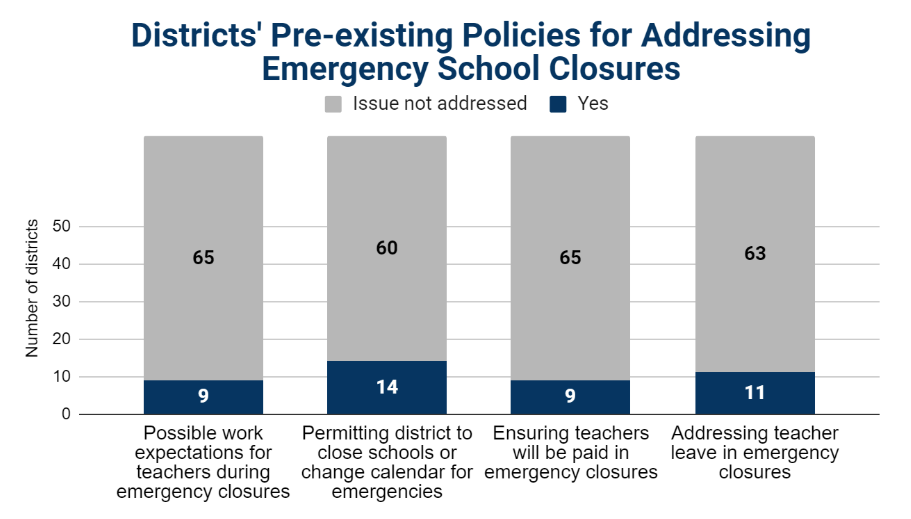

As we had reported previously, few large school districts had pre-existing provisions to address circumstances of long-term emergency closures and delivering remote instruction.

Only a few districts that collectively bargain teacher policies have provisions that require the district and union to formally bargain or even confer over emergency changes to the school calendar, namely Albuquerque, Chicago, Long Beach (CA), Minneapolis, and Shelby County (TN). The most prescient was Orange County (FL), which thought to include language requiring the district to negotiate with the union should a pandemic close schools. But even Orange County could not foresee the many ramifications of this pandemic.

Are districts working with their unions on new policies?

It’s not surprising that many districts have recently started to address this issue, working with their teachers unions to implement policies for remote teaching and learning.

While in early April less than a quarter of the districts in our sample had formal agreements in place about remote teaching, now nearly half of districts in our expanded sample have formally signed agreements addressing the closures and remote teaching and learning. Another quarter are informally working with their teachers unions to issue guidance.

The formal agreements have tackled such germane issues as work hours for teachers, expectations around communicating with students, privacy protections, grading policies, teacher evaluations, and professional development.

How are districts adapting various teacher policies to current circumstances?

Now two months after the closures began, it appears that the majority of large school districts have communicated clear expectations for teachers during remote teaching and learning. The Center for Reinventing Public Education (CRPE) has been expertly tracking the elements of districts’ remote learning plans and their implementation. The CRPE data illustrate how districts have gradually built out these plans with more detail to provide more substantive instruction and feedback to students.

The biggest change we have seen since we first reported on district policy responses in early April is an increase in the percentage of districts where teachers are grading student work. In early April, only 39 percent of our initial sample had communicated that teachers would be grading students during remote teaching and learning, whereas it is now 72 percent.

Many of these large districts, such as Boston, Chicago, the District of Columbia, Los Angeles, and San Francisco, have specified that formal grading will be ‘no-penalty,’ where student work during the closure can only improve but not bring down a grade. Other districts, such as Baltimore City, Cincinnati, and Montgomery County (MD), are grading students as pass/fail or pass/incomplete, or only formally grading students at the high school level, such as in Anchorage and Wichita.

The decision about whether to grade student work has been less about the concern of overburdening teachers (though providing formal feedback in a remote setting is certainly more challenging) and more about being fair to students without sufficient access to the requisite technology and resources. Large districts have sought to balance the need to provide students with feedback, and ensure academic records and grade promotion systems can still function, while also not penalizing students who, through no fault of their own, have been unable to complete assigned work.

Most districts have expectations that teachers communicate with students regularly (with the most common policy being once a week) and some have set a minimum number of virtual “office hours” each week when teachers must be available to students, whether the teacher is providing synchronous or asynchronous instruction.

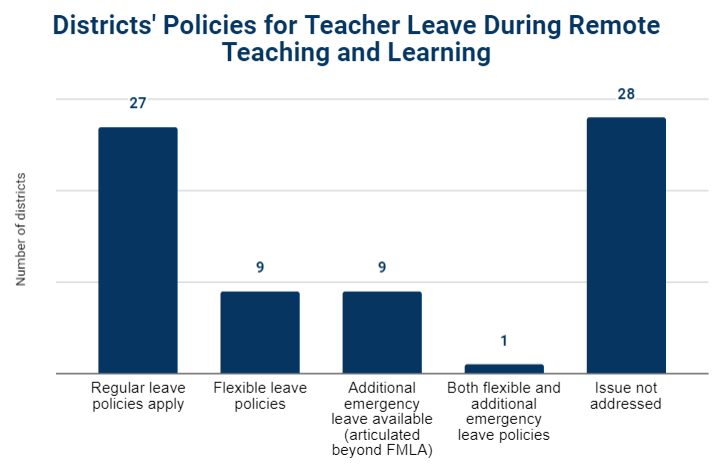

Many large districts, about 40 percent of our sample, have not articulated any formal rules regarding teachers taking leave during the remote teaching and learning period. For those that have, the majority have clarified that existing personal and sick leave provisions apply to teachers while they work from home.

Other districts, such as Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools (NC) and Denver are providing additional fully-paid emergency leave for teachers affected by COVID-19, beyond FMLA. The four largest districts in the country, Chicago, Los Angeles, Miami-Dade, and New York City, are among those that communicated flexible leave policies for teachers during this time. Flexible policies allow teachers to take time off during the work day without going through the formal leave request and reporting process.

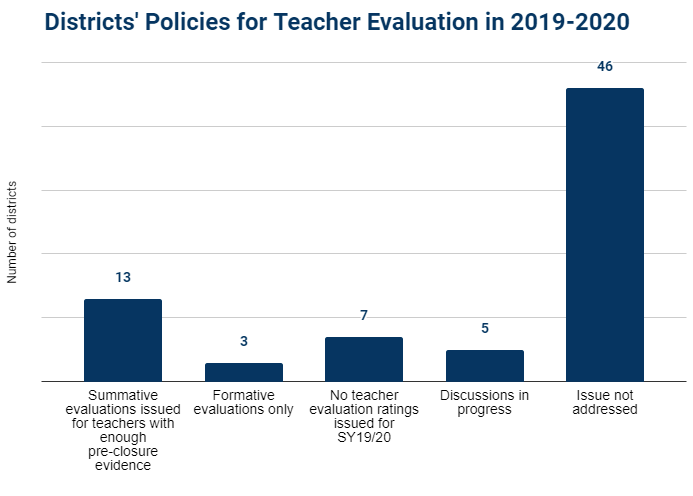

As of writing, most states have issued waivers or guidance on their teacher evaluation processes as a result of the pandemic. Most large districts, however, have not yet publicly articulated what they are doing about teacher evaluations for 2019-2020.

As we reported earlier this month, the most common policy large districts are adopting is to ensure that at least some, if not most teachers receive a summative evaluation for 2019-2020, using sufficient evidence that was collected before the physical closure of schools. Some districts, such as Providence (RI) and Seattle have decreased the minimum required number of classroom observations. Others, such as Chicago and Houston, are calculating summative ratings based on measures besides student growth, as the cancelation of state-wide assessments means those data are unavailable.

A few districts are only issuing formative evaluation feedback to teachers for this year, while seven so far have declared no summative evaluations will be issued for teachers.

What’s next for teacher policies as districts look to next year?

At this point, few people believe that school will be back to normal in the fall. States are starting to reopen, but many teachers and parents are uncomfortable with the idea of returning to physical school buildings, and education leaders are starting to think about what school might look like in the absence of a widely available vaccine.

Some school districts, such as Atlanta and Dallas have already codified new provisions for long-term emergency closures and remote teaching and learning in their board policies. In districts that collectively bargain teacher policies, most of the formal agreements negotiated with unions to respond to the crisis sunset in June or at the end of this school year. Some may negotiate new temporary agreements to address the policy needs of next school year, but more likely, school districts and unions will add sections to collective bargaining agreements in the future that incorporate the lessons learned from COVID-19.