School districts currently hire about 70,000 new elementary teachers each year, with the expectation that these teachers are ready to teach the standard elementary curriculum of English language arts, mathematics, science, and social studies.[1] Yet many of these novices report being ill-equipped to do so—often in spite of having passed a licensing test in these subjects. There are also a lot of aspiring teachers ‘left behind’—those unable to pass their tests. The field of teaching has an exceptionally high number of candidates who fail their tests relative to other professions such as nursing. A disproportionate number are candidates of color—a big setback for school districts’ efforts to diversify their teacher force.

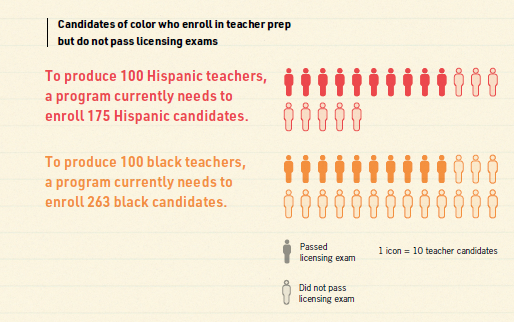

NCTQ’s new report, A Fair Chance: Simple steps to strengthen and diversify the teacher workforce, reveals that more elementary teacher candidates fail their licensing tests on their first attempt (54 percent) than pass them. At the same time, few institutions require that teacher candidates take the coursework that would prepare candidates to do well both on the test and in the classroom.

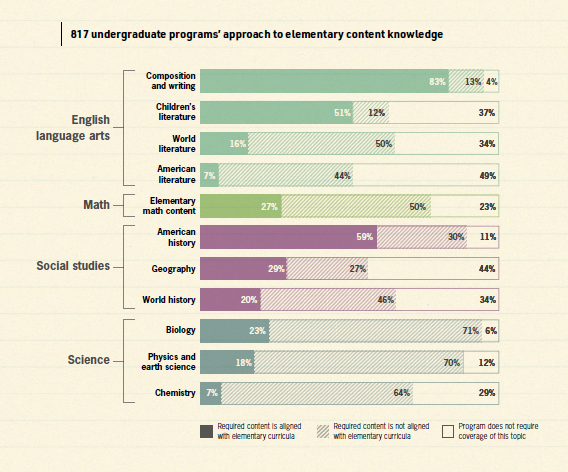

The report examined programs in over 1,000 institutions, including 817 undergraduate programs. Analysis considered both the ‘general education’ coursework required of all students at an institution and the coursework required by the teaching major. It was the rare program in the nation that made sure candidates took courses to shore up knowledge gaps they had, building their knowledge in the topics common to the elementary classroom.

Six big reasons this problem is likely hurting your school district

1. Weak content knowledge keeps thousands of teacher candidates of color from reaching the classroom. Already more likely to be disadvantaged by inequities in K-12 education, only 38 percent of black teacher candidates and 57 percent of Hispanic teacher candidates eventually pass the most widely used licensing test, compared to 75 percent of white candidates. More than half the candidates of color who enter teacher preparation programs do not pass licensing tests.

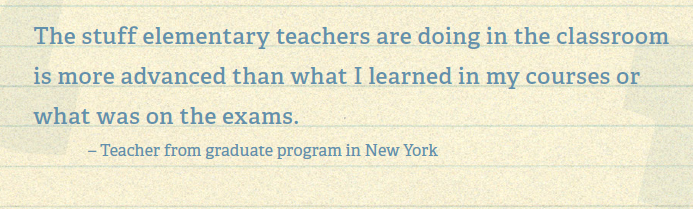

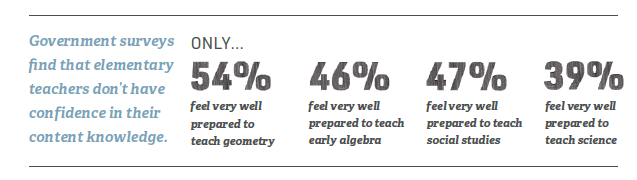

2. The tests signal a deeper problem that can’t be solved by just getting rid of the test. The truth is that elementary teachers, even those who have passed their licensing tests, still report a lack of confidence in the content their school districts want them to teach.[2]

3. Teachers may give superficial coverage or completely avoid teaching content where their knowledge is weak—a detriment to fulfilling one of their most important jobs: building students’ reading comprehension. Reading comprehension is much more than learning skills like inferring and finding the main idea. It depends on children learning “background knowledge” across a whole variety of subject —many falling under social studies and science. The more students learn about various topics, the larger their vocabulary becomes and the better they will comprehend what they read.[3]

4. Students learn more in math when taught by teachers with greater mathematics content knowledge.[4] Not surprisingly, teachers teach elementary math topics more completely when they learned about those topics during their preparation program, while they spend less time on topics their programs did not cover.[5] For more about the kind of coursework elementary teachers need, visit the Teacher Prep Review’s materials on elementary mathematics.

5. Teachers who don’t know the content all that well are probably less likely to give their students appropriately challenging assignments. A 2018 TNTP study found that “few… assignments gave [students] the chance to demonstrate grade-level mastery.” For assignments from kindergarten through grade 5, only a quarter of English language arts assignments (28 percent) and half of math assignments (48 percent) were based on grade-level content.[6]

6. Teachers’ content gaps create an endless cycle, reinforcing our inequitable education system. Schools with higher rates of poverty and more students of color are more likely to have teachers with less experience, lower value-added scores, and weaker content knowledge.[7] This inequitable distribution of teachers likely contributes to the next generation of students of color with gaps in their content knowledge.

Teacher prep programs miss an opportunity to fill in knowledge gaps

The responsibility for low passing rates does not rest wholly at the feet of teacher preparation programs, but these programs are in the best position to take action. They largely miss opportunities to identify and shore up their candidates’ knowledge gaps.

The dearth of content coverage is unmistakable

- While most programs require teacher candidates to take a course in composition and writing, they seldom require a literature course aligned with what elementary teachers will need to know. Notably only half require an aligned children’s literature course.

- Only one in four programs covers the breadth of mathematics content relevant to teaching elementary grades.

- One in three programs does not require a history or geography course aligned with the needs of elementary teachers.

- Two in three programs do not require a single science course aligned with what elementary teachers will teach.

A solvable problem

You can easily look up whether your local prep programs cover core elementary content by going to Appendix A.

Help advocate for the straightforward changes institutions and their programs can make to improve candidates’ elementary content knowledge. Urge your institutions to take the following steps:

- Provide better parameters for selecting from course options that count toward general education requirements for undergraduate students who indicate an interest in teaching.

- Use the teacher preparation program admissions process as an opportunity to identify weaknesses in content knowledge and then tailor the course of study to fill in gaps.

- Set undergraduate and graduate program content course requirements to align with what elementary teachers need to know.

Read the full NCTQ report here: https://www.nctq.org/publications/A-Fair-Chance

[1] Warner-Griffin, C., Noel, A., and Tadler, C. (2016). Sources of Newly Hired Teachers in the United States: Results from the Schools and Staffing Survey, 1987– 88 to 2011–12 (NCES 2016-876). U.S. Department of Education. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch.

[2] Banilower, et al. (2013). Report of the 2012 National Survey of Science and Mathematics Education. Horizon Research, Inc. Retrieved November 1, 2018, from http://www.horizon-research.com/2012nssme/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/2012-NSSME-Full-Report1.pdf.

[3] Hirsch, E.D. (2006.) The knowledge deficit. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company; Willingham, D. T. (2006.) How knowledge helps: It speeds and strengthens comprehension, learning — and thinking. American Educator, 30(1), 30-37

[4] Campbell, P. F., Nishio, M., Smith, T. M., Clark, L. M., Conant, D. L., Rust, A. H., DePiper, J. N., Frank, T. J., Griffin, M. J., & Choi, Y. (2014). The relationship between teachers’ mathematical content and pedagogical knowledge, teachers’ perceptions, and student achievement. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 45(4), 419-459; Kukla-Acevedo, S. (2009). Do teacher characteristics matter? New results on the effects of teacher preparation on student achievement. Economics of Education Review, 28, 49-57; Hill, H., Rowan, B., & Ball, D. (2005). Effects of teachers’ mathematical knowledge for teaching on student achievement. American Educational Research Journal, 42(2), 371-406.

[5] Morris, A. K., & Hiebert, J. (2017). Effects of teacher preparation courses: Do graduates use what they learned to plan mathematics lessons? American Educational Research Journal, 54(3).

[6] B. Cato. (2018). The opportunity myth: What students can show us about how school is letting them down – and how to fix it. Retrieved October 17, 2018, from https://opportunitymyth.tntp.org/. (Personal communication based on data from TNTP).

[7] Goldhaber, D., Lavery, L., & Theobald, R. (2015). Uneven playing field? Assessing the teacher quality gap between advantaged and disadvantaged students. Educational researcher, 44(5), 293-307. Goldhaber, D., Quince, V., & Theobald, R. [2016]. Has it always been this way? Tracing the evolution of teacher quality gaps in U.S. public schools [CALDER Working Paper 171]. Washington, DC: National Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research; Clotfelter, C., Ladd, H. F., Vigdor, J., & Wheeler, J. (2006). High-poverty schools and the distribution of teachers and principals. NCL Rev., 85, 1345.

More like this

Gambling with children’s futures—and no one’s tracking whether we win or lose

How some states use licensure test pass rate data to build a stronger, more diverse teacher workforce

Setting sights lower: States back away from elementary teacher licensure tests