As students go back to school, high school seniors considering college know they have just a few months to narrow down their application choices. In today’s economy, it is natural for them to worry about how their college choice will affect their future job prospects. They hunt information on the Internet, in college guidebooks, from guidance counselors, and on college tours to find out, “Will attending this college help me get a job?”

This is especially true for aspiring teachers. Having decided on teaching as their future profession, they desire specifics on which teacher prep programs will provide them with the best path to a teaching position. So, aspiring teachers understandably want data on the percentage of graduates from each college who obtain a teaching job.

For institutions, this question raises some interesting questions about colleges’ responsibility for their students’ futures. Should schools of education steer their students to fields where they have the highest chances of being hired? Or should they allow students to major in fields in which the college knows only a few will eventually find jobs?

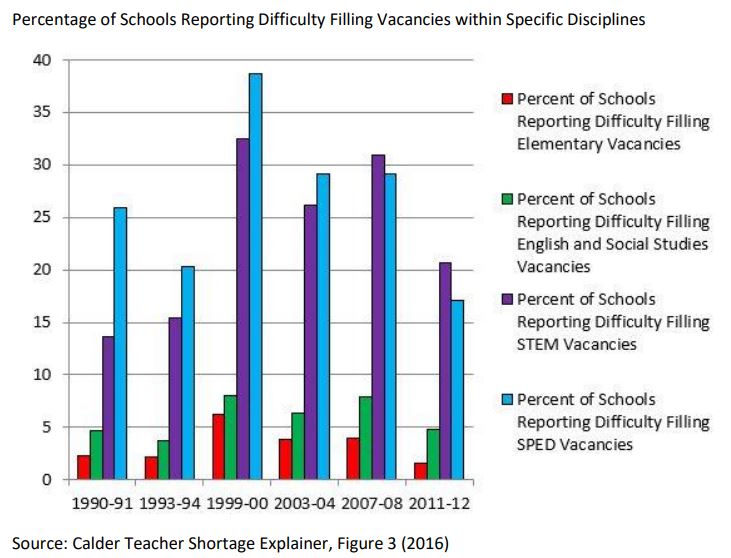

Everyone in teacher education knows that some states and some teaching fields have more shortages than others. Schools are always looking for special education teachers, English as a Second Language teachers, and teachers of math and science. By contrast, teachers trained in elementary education and social studies will face more competition for jobs, as these certification areas are among the most popular. Knowing this, do teacher prep programs face any responsibility to recommend that applicants to their elementary education program consider adding dual-certification in ESL or special education? Should they refuse to enroll aspiring teachers to a social studies education major unless they agree to minor and obtain dual certification in a more sought-after field? Or should they insist prospective teachers major in a liberal arts field and take education as a minor?

On the one hand, teacher preparation programs educate their students to do a specific job; if few openings are available in their field, most students will have wasted their time and money. Colleges are supposed to educate the young, so advising students on their career prospects is part of their mission. Just as education professors should show aspiring teachers the best teaching techniques, they should advise on the best strategies for job seeking. Teacher preparation is highly specialized professional training and so is more directly linked to specific jobs than are majors in liberal arts programs, whose students can major in History or Film and go on to graduate school or a job not specifically tied to the major. Also, since employed graduates are happier graduates, colleges have a key reason to prepare students in a specialty where jobs are plentiful.

On the other hand, college students are supposed to be adults, capable of making their own decisions. Colleges are in the business of educating students for the future, not restricting their futures. Other divisions of the college do not steer fine arts students to major in finance instead, nor tell classics students to double major in chemistry. A student who really wants to be an elementary teacher could be more motivated (and therefore more successful) in that major than she would if persuaded to major in math education. Also, colleges maintain that any of their majors train students in how to research, reason, and communicate. So even if graduates cannot find a teaching position in their specialty area, they can use this education for other employment.

There is precedent for requiring colleges to become more involved in college students’ success after graduation. Although there are no federal rules requiring bachelor-level teacher education programs to maintain any specified employment percentage, the federal government has “gainful employment” rules that apply to non-degree career education programs and certificate programs at higher education institutions receiving federal student aid. These rules require that graduates’ annual payments on their student loans should be no more than 8 percent of total earnings. While institutions have challenged these rules in the courts and the current administration’s Education Department has put “gainful employment” on hold pending a rewrite, they do show an attempt to hold higher education accountable for graduates’ success.

Higher education institutions themselves recognize that they play a role in their graduates’ subsequent careers. They maintain career counseling and job finding services for students and even alumni. Many organize job fairs to connect students with would-be employers. Their promotional materials frequently tout the power of connections students make on campus and through the school’s network of alumni. And certainly, colleges of education link their curricula to state certification requirements. If colleges can be involved in their graduates’ careers in all these ways, why would steering students to the teaching fields with the most openings be beyond the pale?

Some graduate schools and professors are considering limiting the number of admissions to their programs based on the availability of jobs. First year enrollment in law school dropped after 2010 and 2011 when the number of first year law students was twice the number of new graduates employed in full time legal jobs. While most of this drop was due to students deciding against applying to law school due to low employment, many institutions have chosen to cut admissions rather than fill open slots with less qualified students.

Teacher preparation programs may be best off walking a middle ground on this dilemma by providing information about job prospects, and then allowing aspiring teachers to choose their major with full knowledge of the career consequences. They could ask students which is more important to them — becoming a teacher even if it is in a different field or working in a nonteaching job in their desired subject? They also can encourage these future teachers to double major or take additional courses that could lead to dual certification. Teachers, in any subject, will be more attractive to employers if they are also certified in special education, fluent in Spanish, or additionally are licensed to teach math or science.

Colleges understandably do not want to be in a position of denying or even discouraging a young person’s dream of becoming a teacher in a favorite academic area or age range. But as teacher shortages are limited to certain subjects and locations, colleges will have to determine the extent of their responsibility to guide their students to improve their employment chances.

More like this

Start at the Beginning: Understanding the earliest part of the teacher pipeline can improve recruitment

Teacher Apprenticeships: Long on possibility, short on details (for now)

Data Brief: How do trends in teacher preparation enrollment and completion vary by state?