Reducing class size is popular among teachers, parents, and politicians. Research has found smaller classes benefit certain populations, specifically students in early childhood grades, students living in poverty, and students of color, but the costs can be considerable and the implementation complicated. Recent years of data suggest class sizes are steadily shrinking, yet when looking at district policy in 2016 and then again before (2019), during (2021), and now after the pandemic, the change appears to be driven both by declines in student enrollment and growth in the number of districts with a class size policy, as opposed to districts lowering their class size limits.

To explore current district policy and examine how class size limitations have changed in recent years, this District Trendline looks at class size policies for 148 of the largest school districts in the United States1 and provides examples of districts using approaches that improve student outcomes.

The shrinking classroom

Between 1950 and 1995, student-teacher ratios fell by roughly 10 students per class, yet there was no corresponding improvement in student performance.2 More recent NCES data continues to find student-teacher ratios in decline, while NAEP reading and math scores remain stagnant.

Research has repeatedly found that it is the quality, not quantity, of teachers that correlates most directly with student achievement. Because policy decisions are typically a choice about the most effective use of a dollar, class size reduction policies are often inefficient due to the need to to build more classrooms and hire additional teachers, stretching budgets and potentially diluting teacher effectiveness.3

It is therefore important to recognize that while class size reduction has the potential to improve student outcomes, it is an intervention that comes with costs and limitations. For example, one study found students in smaller K-3 classes outperformed their peers in reading, but that effect was only observed when classes declined to 15 or fewer students, and there were only minimal gains in mathematics.4 Whether or not 15 students is the critical count, with the average class size steadily shrinking and no significant changes in student outcomes, it appears unlikely that achievement will suddenly spike once a particular threshold is crossed.

Average class size in public schools5

Increased presence of class size policies

Since 2016, the percentage of districts in our sample with class size limits has jumped from 68% to 90%, with state policy playing a direct role. Among the 133 Teacher Contract Database (TCD) districts with class size limits for at least one grade, 40% are simply adhering to thresholds set by the state.

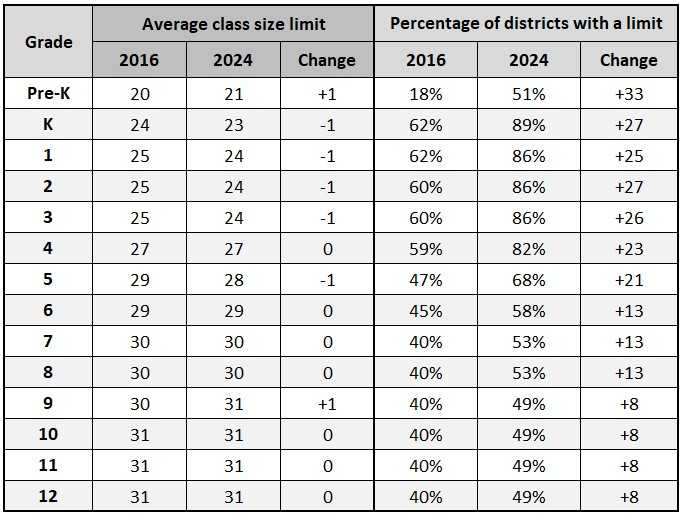

When looking at class size restrictions and the number of districts setting such limits (Figure 2), diverging stories emerge. Across all grades, the average class size limits have only changed slightly since 2016. There were some marginal increases and decreases among the limits, but on the whole, there isn’t evidence of a pronounced push to expand or shrink class sizes. Further, actual average class sizes often fall below class size limits. For example, the average class size limit for seventh grade is 30 whereas the average middle school class has 22 students.6 This may indicate that existing policies have been effective, but also suggests that continued reductions are less likely.

Grade level class size findings in TCD districts

Due to rounding, the calculated percentage point change may differ from the presented percentages

While the limits themselves are generally the same as they were eight years ago, the presence of policies across all grades has increased. For example, a majority of districts (51%) now have class size limits for Pre-K, up from just 18% in 2016, and almost 9 in 10 districts have limits for grades K-3, which are meaningful shifts given research indicating that children in early grades benefit from smaller classrooms.

Of course, the averages are produced by a range of class size limits. Looking at kindergarten, where the greatest number of districts set a threshold (see Figure 2), 26 districts—almost entirely driven by state policy in Alabama, Florida, and Georgia—have class size limits of 18 students. On the other end of the spectrum, excluding the 17 districts without a maximum class size, the largest threshold belongs to San Bernardino City Unified School District (CA) and Buffalo School District (NY) where kindergarten classes are capped at 33 students.

Figure 3.

It’s important to note that the data in Figures 2 and 3 is not inclusive of districts that attempt to control class size through adjacent policies. For example, Oklahoma specifies that teachers in grades 7-12 cannot exceed 140 students during any given day, but does not provide any parameters for individual classes. This means that if those 140 students are spread across six classes, a teacher would have roughly 23 students in each, whereas that count could jump to 35 students if the same teacher only taught four courses. As another example, instead of a cap for all classrooms, New Mexico policy states that the average class load for an individual elementary school cannot exceed 22 students in grades 1-3 or 24 students in grades 4-6.

There is undoubtedly benefit in providing flexibility, but what repercussions do schools or districts face when they cross thresholds?

Policy without consequence

Despite the growth of class size policies, just 56% of districts define formal consequences for exceeding established limits. The remaining districts appear to leave the penalty for exceeding class size limits undefined. It is notable that the percentages of districts under each category have almost all increased over the last five years. It’s also worth recognizing that many of the consequences fail to reduce class sizes.

Defined actions for exceeding class size limits in TCD districts

Districts with policies that have multiple options for when class sizes are exceeded are counted in each instance. In the 2024 counts, 41 of the 78 districts with defined consequences appear in at least two categories.

Santa Ana Unified School District (CA) is one district that stands out for setting different consequences for different grades. Presently, when schools breach limits in elementary grades, they must add additional staff, while exceeding limits in middle and high school means teachers receive additional compensation. What’s more, the current CBA specifies, “The District shall establish a class size problem resolution committee at each level (elementary, intermediate, and high school) to study and suggest methods of relief in buildings to reduce split-grade classes, to reduce the impact of low enrollment classes, to allow for large group or experimental instruction, and/or team teaching.”

What’s the right policy move?

Classes are getting smaller, but student achievement is not improving. More districts are setting class size limits, but exceeding those limits often lacks consequences and adhering to limits may not improve student achievement.

A review of the research suggests that “right-sizing” classrooms is the most viable and cost-effective intervention to reap the benefits of class size reduction without diluting teacher quality. Assigning more students to highly effective teachers’ classrooms, and compensating those teachers accordingly, may improve academic performance for all students by increasing students’ access to effective teachers while decreasing class loads for other teachers. What’s more, increasing compensation for effective teachers is likely more cost-effective than hiring new teachers.7 Recent survey findings reveal that 96% of teachers would be willing to expand their class size in exchange for a $10,000 salary increase. To make this possible, though, districts must be able to evaluate teacher effectiveness and assign students accordingly. Additionally, class size limits cannot function as suggestions. When schools exceed caps, there should be clearly defined actions that provide relief.

Thoughtful approaches

Staffing levels hit an all-time high in the 2022-2023 school year, but as Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) funds run out, districts will not be able to maintain existing levels, suggesting that layoffs are looming. With student enrollment on the decline, it simply won’t be possible for districts to keep as many teachers on their payrolls. Given that class size is more likely to grow than shrink in the coming years, districts should support targeted approaches to keep class sizes in check.

Age-focused restrictions: North Carolina only sets class size restrictions for grades K-3, whereas Florida sets limits all the way from Pre-K to grade 12. In the face of declining budgets that may cause states and districts to reconsider some of the class size limits on the books, following North Carolina’s model or at least holding the line on the early childhood grades is supported by research.

Socioeconomic restrictions: In Minnesota, both Minneapolis Public Schools and St. Paul Public Schools differentiate class size restrictions based on school poverty levels. As one example, Minneapolis Public Schools caps third-grade classrooms at 25 students in schools where 70% or more students are eligible for free and reduced lunch (FRL), while allowing up to 34 students per classroom in schools that fall below 70% FRL.

Population-focused restrictions: Another consideration for districts exists around students who require accommodations. Boston Public Schools sets limits for schools based on the percentage of students with an individual education plan (IEP). For example, in grades 3-5, schools at or below 6.5% of students on IEPs can have up to 25 students per class. Where that threshold is exceeded, classes are limited to 23 students.

Strategic staffing models: An additional approach may be to reimagine how classes are structured by creating teams of teachers who share a roster of students. In these models, teachers work together with other adults, such as paraprofessionals, teacher residents, or tutors, to serve a larger class of students. Highly effective teachers may earn more for teaching more students. These approaches also present an opportunity for teacher leadership and career advancement by having teachers serve as team leads. Early research shows this approach, which typically disrupts class size limits, could be promising for teachers and students alike. An expanded look at strategic staffing models will be the focus of a forthcoming NCTQ report on state policies for redesigning teacher roles.

More like this

How long is your school year? It depends—a lot—on where you live

This District Trendline looks at the 2023-2024 calendar for large school districts in the United States to explore the makeup of academic years.

Comparing school districts on class size policies

Working conditions play a crucial role in teachers’ wellbeing, especially after 18 taxing months of reinventing education due to the pandemic. A recent report uncovers that class sizes are a major contributing factor. In this month’s District Trendline, we examine the contractual obligations of 148 school districts for class sizes.

A sizable opportunity: thinking strategically about class size

Endnotes

- The sample for this analysis, drawn from NCTQ’s Teacher Contract Database, consists of 148 school districts in the United States: the 100 largest districts in the country, the largest district in each state, and the member districts of the Council of Great City Schools.

- Hanushek, E.A. (1999). The Evidence on Class Size. In Mayer, S. E., & Peterson, P. E. (Eds.). Earning and learning: How schools matter (pp. 131-168). Brookings Institution Press.

- Krasnoff, B. (2014). Class Size Reduction. Northwest Comprehensive Center at Education Northwest.

- Dynarski, S., Hyman, J. M., & Schanzenbach, D. W. (2011). Experimental evidence on the effect of childhood investment on postsecondary attainment and degree completion. National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Data in this table is drawn from the NCES National Teacher and Principal Survey releases in 2015-2016, 2017-2018, and 2020-2021. Data is currently being collected for the 2023-2024 academic year.

- Based on 2020-2021 class size data. Given that the trend has been toward smaller classes since at least 2015-2016, it’s likely that the average middle school class size currently falls below 22 students.

- Hansen, M. (2013). Right-sizing the Classroom: Making the Most of Great Teachers. Thomas B. Fordham Institute.