This month, the District Trendline highlights the role of collective bargaining in teacher strikes, takes a look at what teachers have won in recent strikes in Denver, Los Angeles, and Oakland, and makes a prediction of where teachers might strike next.

The role of collective bargaining

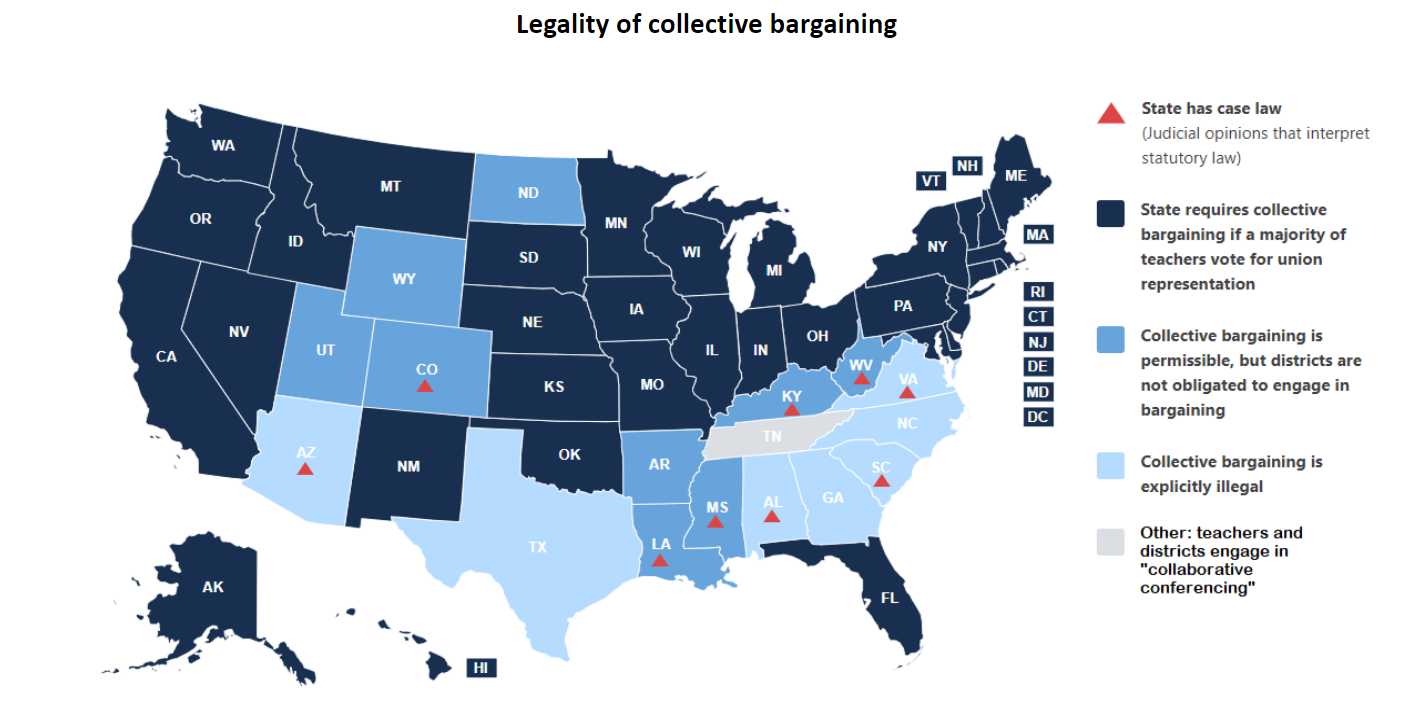

Traditional teacher strikes occur when a teachers union and a school district cannot come to an agreement around various work issues through a process known as collective bargaining. Collective bargaining is legal for teachers in 34 states, optional in an additional 10 states, and illegal in seven states. (For more details, visit our interactive map.) Recent examples of this traditional type of strike include Denver, Los Angeles, and Oakland.

In states where collective bargaining is illegal, there is no requirement for the district to reach any kind of agreement with teachers. In general, teacher policies are determined by the school board and communicated through a series of school board policy documents. Of the largest districts in the county, 43 are governed by the policies set unilaterally by school boards, while 80 are governed by collective bargaining or other agreements.

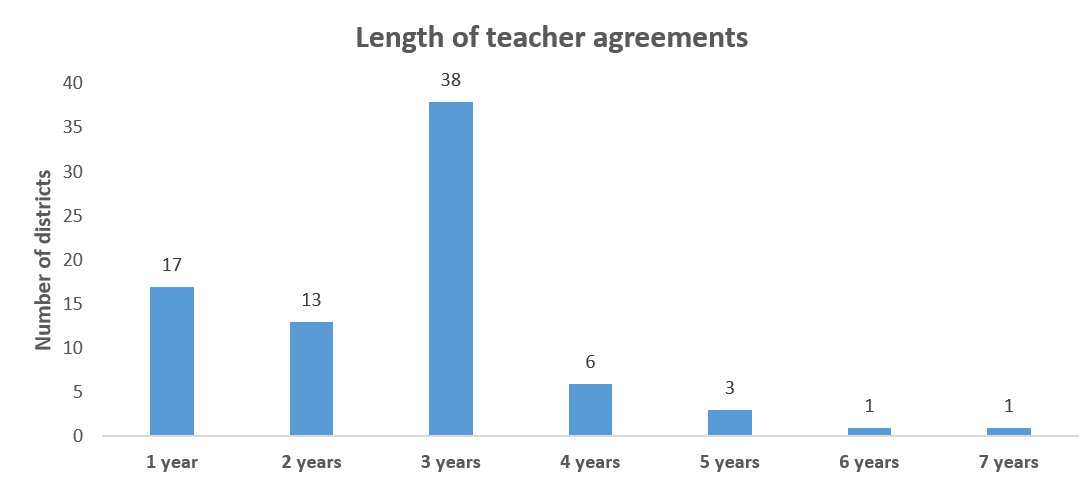

In districts that do collectively bargain, their teacher contracts are, on average, valid for about three years. A not insubstantial number (21 percent), however, go to the bargaining table every year.

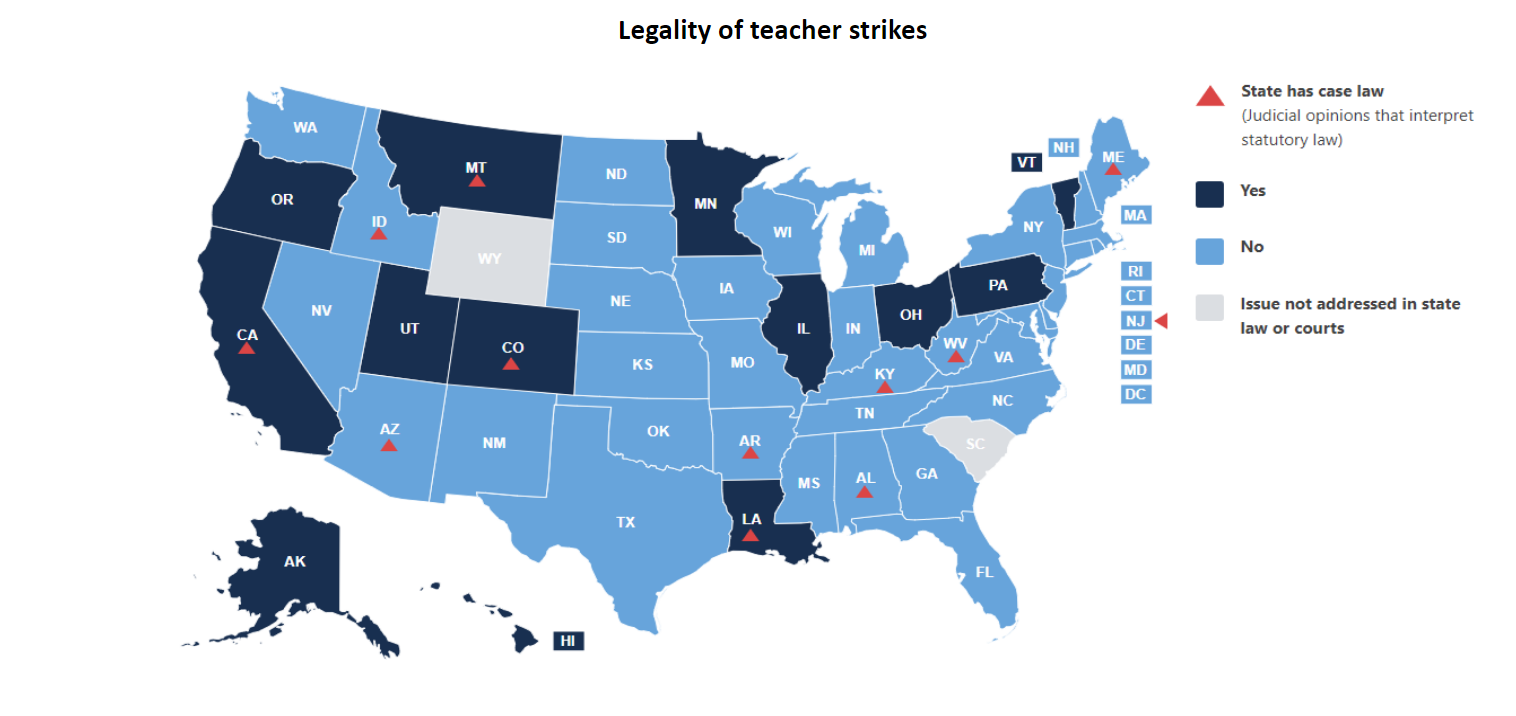

Where is it legal to strike?

About a quarter of the largest districts in the country are located in one of the 13 states where a teacher strike is legal. (To learn more, visit our interactive map.)

Of course, just because a state has a law prohibiting teacher strikes does not always mean teachers will adhere to those laws. Striking was illegal in most of the states that had statewide walkouts in the spring of 2018. There were also widespread strikes in the state of Washington last fall, where striking is technically illegal.

Who will strike next?

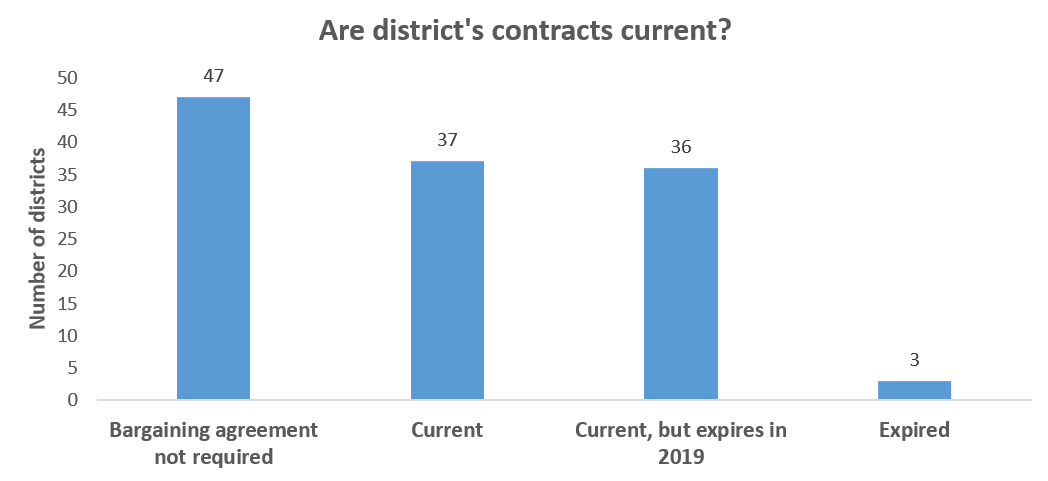

Perhaps the best predictor for which district might strike next is the combination of being located in a state where it’s legal to strike and also having a collective bargaining agreement that is expired or soon-to-be expired.

Among the largest districts in the country, only three have currently expired agreements (Boston, Brevard (FL), Manchester (NH)). However, none of these three districts are located in states where it is legal to strike. While this doesn’t preclude a strike, it does make it much less likely.

On the other hand, there are 36 large districts with collective bargaining agreements that are set to expire this year. Thirteen of these districts are in states where it is legal to strike, including five California districts (Capistrano, Elk Grove, Fresno, San Bernardino City, Santa Ana) where there have already been two teacher strikes in 2019 and where two more districts are threatening to strike.

While predicting a strike is tricky, Sacramento (CA) is a good bet. Teachers there have already approved a potential strike over unfair labor practices. Another place to keep an eye on is Chicago, where the president of the Chicago Teachers Union has warned teachers to start saving for a potential strike in the fall should the need arise. The Chicago Teachers Union has shown a penchant for using the threat of a strike as a bargaining strategy in the past and they have already issued a list of demands for their upcoming negotiations.

A look at recent strikes

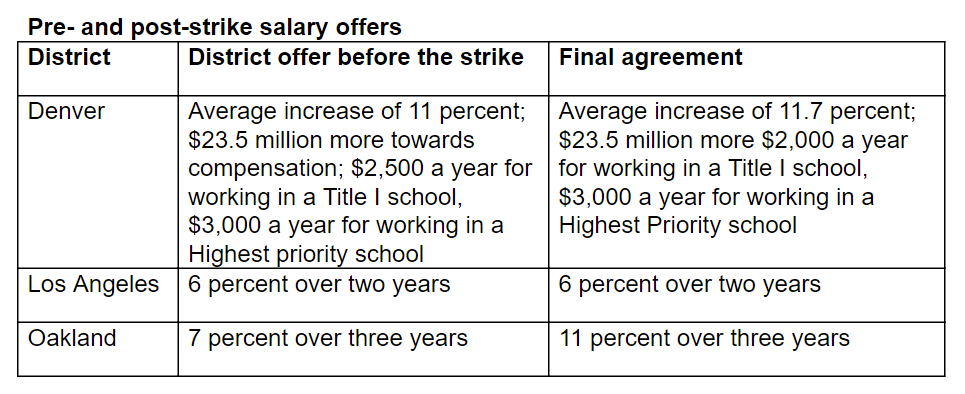

The issues that prove to be the reason why teachers choose to strike vary from district to district, although they frequently focus on teacher compensation and class size. We wondered if going on strike actually results in substantially better offers from districts, so we took a look at what teachers in Denver, Los Angeles, and Oakland have won in their recent strikes.

In both Denver and Los Angeles, teachers ended the strike with the same amount of money going towards raises as was on the table before the strike. However, in both cases teachers won other concessions from the district. In Denver how the new salary money is distributed bent in the union’s favor, with the district reducing a bonus for teachers working in Title I schools, among other changes to the compensation structure. In Los Angeles, the union won a significantly larger investment in support personnel and class size reduction.

In Oakland, teachers received significant salary increases in comparison to previous district offers, ultimately winning an 11 percent increase over three years compared to the pre-strike district offer of seven percent. In addition, Oakland teachers won some minor concessions regarding restrictions on class size.

Of course, these agreements do not come without a cost. Both Denver and Oakland are laying off hundreds of non-teacher employees to offset the costs of their agreements. In Los Angeles, the district faces real financial concerns including a potential takeover by the county due in part to the fiscal risk of implementing the new agreement.

You can learn more about state collective bargaining laws here and explore teacher collective bargaining agreements, districts’ salaries, and key data in our Teacher Contract Database.

More like this

Do state collective bargaining rules influence district teacher policies?

An analysis of state rules on collective bargaining for teachers and the content of school districts’ policies across 148 districts nationwide.

How will the upcoming Janus Supreme Court case impact teachers in each state?

In light of the upcoming Supreme Court oral arguments on the highly significant Janus vs. AFSCME case, we took a look at state laws regarding collective bargaining and the type of fees that teachers unions are currently allowed to collect, depending on the state in which they are organized.