District Trendline, previously known as Teacher Trendline, provides actionable research to improve district personnel policies that will strengthen the teacher workforce. Want evidence-based guidance on policies and practices that will enhance your ability to recruit, develop, and retain great teachers delivered right to your inbox each month? Subscribe here.

According to the National Center for Education

Statistics, roughly eight percent of teachers move schools each year. Of

the teachers that are movers, almost one third are forced to change schools

through an involuntary transfer. In this edition of the Trendline, we

take a look at the policies that govern voluntary and involuntary transfers, plus

we take a deeper look at districts that use mutual consent policies to assign

transferring teachers to new schools.

Identifying

involuntary transfers

For a variety of reasons, teachers are sometimes involuntarily

transferred from one school to another. The primary reason for this is excessing.

Excessing occurs when positions are eliminated because of a change in student

enrollment, budget cuts, or programmatic changes. Some districts simply call transfers

due to these circumstances involuntary transfers, but many separate excessing

from other reasons for involuntarily transfers, such as maintaining a specific

racial or gender balance in a building or when a transfer is deemed to be in

the best interest of the district, school, or teacher.

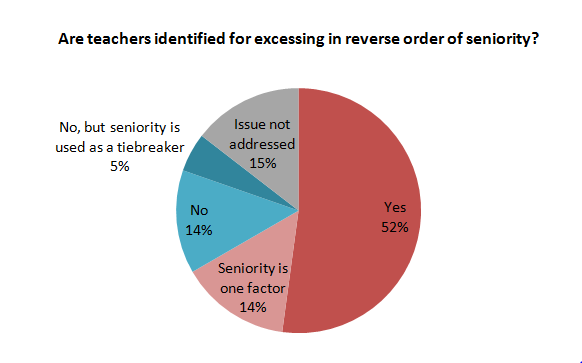

Generally, excessing decisions are based on seniority. In 52

percent of districts in the database, seniority is the determining factor in

identifying teachers for excessing and 14 percent of districts use seniority as

one of multiple factors in the decision.

Seniority is not a primary consideration in nearly one fifth

of the districts in the database; 14 percent do not use seniority in their

decisions and five percent only use seniority as a tiebreaker if all other

factors are equal. In these 22 districts that do not rely on seniority to

determine which teachers get involuntarily transfers, eight explicitly use

performance as a factor.

Assigning involuntary

transfers

Once teachers have been identified for excessing or

involuntary transfer, districts are normally contractually obligated to find

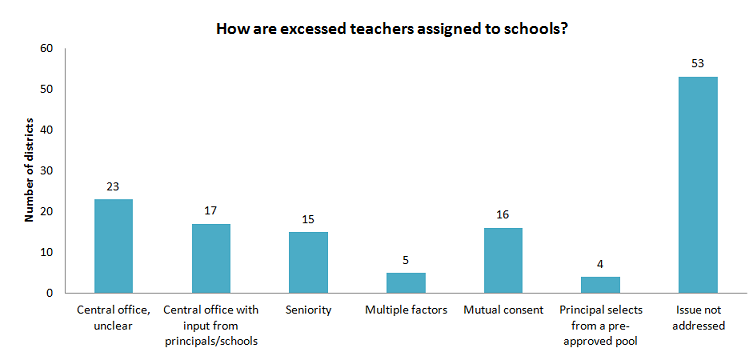

them a new position. In some districts, seniority continues to dictate how

teachers are assigned: 15 districts assign teachers to new schools in order of

seniority and based on their preferences. In the five districts where multiple

factors are considered, four use seniority as one of those factors. In Elgin (IL), teachers are assigned

based on evaluation rankings and seniority is only used as a tiebreaker when

the performance of two teachers is equal.

Principals or school site committees play a role in teacher

re-assignment in 21 districts, either through selecting a candidate from a

pre-approved pool (Chicago, Indianapolis, Aldine (TX), and Cypress-Fairbanks) or through

providing input into a centralized decision making process (17 districts). In

23 districts, the central office ultimately makes placement decisions but how

those decisions are made is unclear.

While less than 10 percent of districts in the database that

do not use mutual consent specify what happens to excessed teachers if a

position cannot be found for them, common practices include giving teachers a

temporary assignment (such as substitute teaching) or simply placing teachers

in a priority hiring pool until a position is found. For example, New York places teachers in the “Absent

Teacher Reserve”

where they continue to be paid as they wait to be placed. Continuing to pay

teachers that do not have permanent positions can be costly for districts; to

avoid this, some districts lay off teachers for whom they cannot find a

position after a given amount of time.

Mutual consent

In 16 districts, finding a teacher a new assignment is done

through the process of mutual consent. In these districts, teachers interview

with principals for a new position and both parties must mutually agree on the

placement. This is an increase from 12 districts that used mutual consent in 2015.

Just because a district uses mutual consent does not mean

seniority does not play a role. In Douglas County (CO), Boston, Denver,Jefferson County (CO), and Cherry Creek(CO), only tenured teachers are allowed to participate in mutual

consent practices. In Providence, Polk County (FL), and Palm Beach County (FL), more senior

teachers receive priority in the mutual consent process.

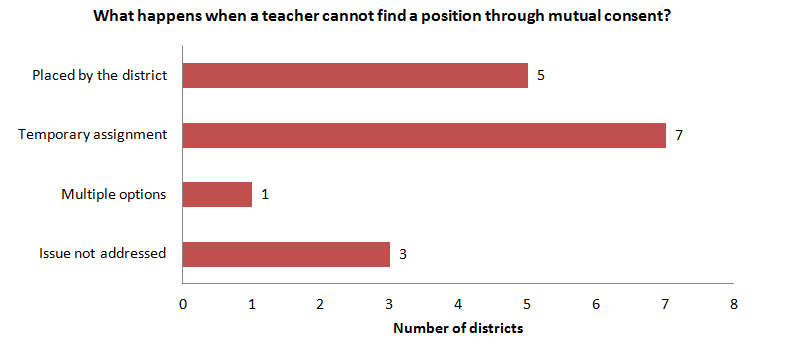

In districts where there is mutual consent,

teachers may fail to find a match. When this happens, five districts place

teachers in any available positions (San Francisco, Minneapolis, Douglas County (CO),

Palm Beach County (FL) and Polk County (FL)), seven districts give unassigned

teachers a temporary position until they can find a permanent position through

mutual consent (Denver, Providence, Boston, Los Angeles, Newark, Seattle, and Jefferson County (CO)),

and one district (the District of Columbia) gives

teachers the option of a temporary assignment, a buyout, or taking early

retirement.

In Denver and Jefferson County (CO), teachers are placed on

unpaid leave indefinitely if, after one year in a temporary position, they fail

to secure a position through mutual consent.[1]

In Providence, temporary assignments can last for up to one year at which

point, if the teacher and principal have not mutually agreed that the teacher

should stay, the teacher must once again go through the mutual consent process.

Voluntary transfers

The majority of teachers that switch schools each year are

voluntary transfers. Teachers may request a transfer to a new school for a

variety of personal or professional reasons. Requesting a transfer generally

comes with low risk as teachers keep their old position until they have been

assigned a new one.

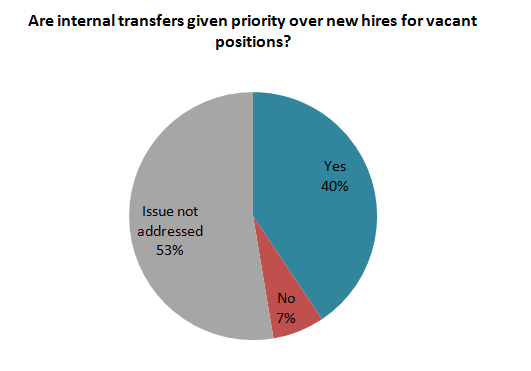

Many districts give formal hiring priority to teachers

within the district seeking a voluntary transfer over new applicants. Just over

half of the districts in the Teacher

Contract Database do not specify who has priority in their transfer

policies; but of those that do, the majority give priority in the hiring

process to transferring teachers over new hires.

There are nine districts that do not give internal transfers

priority over new hires. In Anne Arundel County (MD), Guilford County (NC), Dayton, and Davis (UT), principals must

consider a set number of internal applicants but can also consider outside

applicants. In Newark, teachers seeking a voluntary transfer have the first

opportunity to apply to vacancies, but principals are not required to hire them.

In St. Paul, Nashville, Burlington, and Prince William County (VA),

principals are not required to interview or hire teachers seeking a voluntary

transfer.

West Ada (ID) has a unique policy.

Internal transfers are given priority over new hires unless there are fewer

than three applicants for the same position. If this happens, then all

applicants (including new hires) are given equal consideration. In California,

state law prohibits districts giving preference to transfers over new, qualified

applicants after April 15, but only the contract in Los Angeles reflects this.

In the majority of districts, principals or school site

committees are allowed to select which voluntary transfer applicants to hire,

but there are nine districts where the decision making power is at the

district, rather than the school, level.

To dig into all the details around teacher transfers, download

our data on over 130 school districts.

[1]

This policy, allowed under a Colorado state law from 2010, is currently being challenged

in court.

More like this

Do state collective bargaining rules influence district teacher policies?

An analysis of state rules on collective bargaining for teachers and the content of school districts’ policies across 148 districts nationwide.

Teacher transfers: finding the right fit

Teachers are not interchangeable parts in a school district. That’s why principals need to have the final say about the district’s decision to transfer a teacher into their

school.