Can schools make teachers more effective? In

thinking about that question, your mind probably goes to professional

development or other training activities. But Matthew Kraft and John Papay from Brown University took that query in a different direction, looking

at whether differences in school settings

make teachers more or less effective.

Combining student achievement data with

teachers’ responses to North Carolina’s biannual survey of working conditions, Kraft

and Papay investigated if teachers who worked in higher-rated Charlotte-Mecklenberg schools could

overcome the well-established pattern of poor returns to teaching experience—findings

repeatedly showing that growth in teacher effectiveness is limited largely to

the first few years of teaching.

And guess what? Working conditions do matter—at least in the Charlotte-Mecklenbergschool district. It stands to reason that teachers will

continue to grow and get increasingly effective in orderly buildings with

strong leadership and collaborative environments.

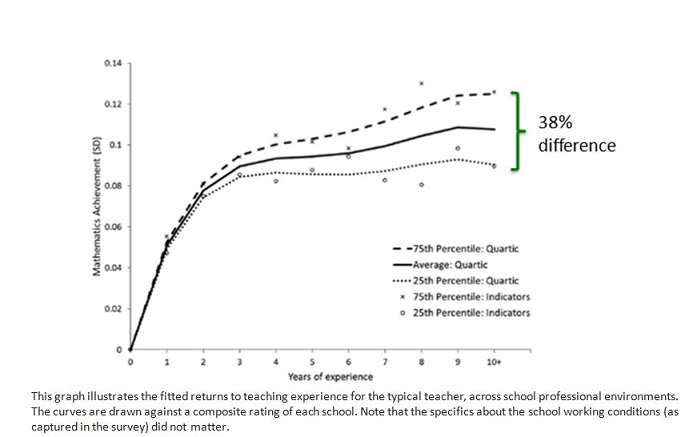

But it’s the magnitude of the difference that is

the real eye-opener. By the end of the first 10 years of a teacher’s career,

there’s a 38 percent gap in student achievement between a teacher at a highly-rated

school and a teacher at a low-rated school.

Unfortunately, the study doesn’t shed any

light on just what the ‘secret sauce’ is in the highly-rated schools, the

qualities about these schools that somehow make it easier for teachers to

continue to grow. The results were based on composite ratings; the specifics of

the working conditions as captured in the survey didn’t seem to matter. And we

can’t help but wonder which is the chicken and which is the egg: Do the working

conditions help teachers get better or does the presence of more effective

teachers impact the professional environment?

Furthermore, would these results hold in

another district, given that Charlotte-Mecklenburg

is well known for its turnaround efforts that have moved effective leaders and

teachers into high-needs schools?

Another recent study makes us think maybe

not.

Zeyu Xu, Umut Özek and Michael Hansen from the American Institutes for Research (AIR) looked at the effectiveness

of teachers who work in high-poverty schools versus those in low-poverty schools

(working paper available here). Tracking the performance of 4th

and 5th grade elementary teachers in North Carolina and Florida

at intervals over ten years, they found no systematic relationship between

schools’ poverty status and teacher performance.

Of course, poverty is a very imperfect proxy

for the working conditions explored by Kraft and Papay above; there are no

doubt high-needs schools that would score well on a teacher survey and

lower-needs schools that teachers would rate poorly. But were Kraft and Papay’s

findings to be generalizable, we’d expect to see some sort of relationship in

the AIR study.

It just may be that the secret sauce is a Charlotte-Mecklenburg local recipe, but

one certainly meriting a closer look.