As scarce as

international studies on teaching generally are, we were glad to see two new

studies looking at what it takes to be a successful math teacher. Both provide

more evidence that there are two distinct types of knowledge relevant to

teaching mathematics: content knowledge and pedagogical content knowledge. The

former is self-evident; the latter involves the capacity to understand possible

student misconceptions, to recognize alternative problem-solving approaches,

and so on.

One study looks at teachers in Belgium (Teachers’ content and pedagogical content knowledge on rational numbers: A comparison of prospective elementary and lower secondary school teachers) while the other focuses on teachers in Taiwan and Germany (Content knowledge and pedagogical content knowledge in Taiwanese and German mathematics teachers). The studies share a few common and not wholly surprising findings:

The two types of knowledge are definitely

different and, fortunately, both can be measured.

The fact that secondary teachers have greater

content knowledge than lower level teachers doesn’t always imply that they have

greater pedagogical content knowledge.

Frankly, the

most interesting piece of information in the two articles is how poorly

Belgium’s elementary and lower secondary teachers performed on a test of

pedagogical content knowledge involving fraction problems (even though Belgian

students outperform ours both as 9-year olds and

15- year olds). It’s well established that American

elementary and middle school teachers are relatively weak in math, but it’s an

eye opener to see that on a math problem involving division by a fraction, 86

percent of teachers in higher-ranked Belgium were incorrect.

In any case,

this revelation of the difficulty elementary and middle school teachers have

with fractions no matter what side of the pond they’re on poses an excellent

opportunity to show very graphically the difference between two elementary math

textbooks we’ve evaluated and how each takes a very different approach to

developing both content knowledge and pedagogical content knowledge.

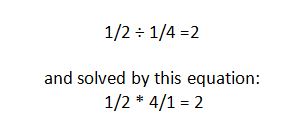

First a bit of math on the topic of division by

a fraction: Teachers should most definitely not reinforce the idea that the basis for this operation is

a mystery. (“Ours is not to wonder why, just invert and

multiply!”) A good teacher can demonstrate the two types of situations

modeled by this equation:

In the first

situation, we’re finding out how many quantities of 1/4th are in 1/2 (there are

2); in the second situation, we’re

finding out that if we did 1/4th of a job with 1/2 of a quantity, it will take

2 of the quantity to complete the job.

(Keep

reading. No one said this was easy!)

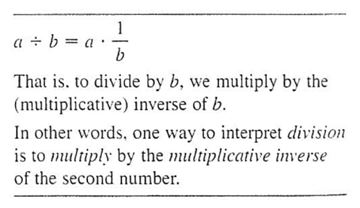

Here’s how a

textbook to which we gave a low score (Mathematics

for Elementary School Teachers, Bassarear, 5th ed.) presents this topic on p. 280:

There’s half a page of discussion that draws on the use of the multiplicative

inverse in an abstract way and provides no explanatory graphic. In fact, the

author explains, “Unlike most of the other algorithms we have examined,

[the invert-and-multiply algorithm] does not lend itself to a diagrammatic

representation.”

Here’s the final part of the explanation

offered:

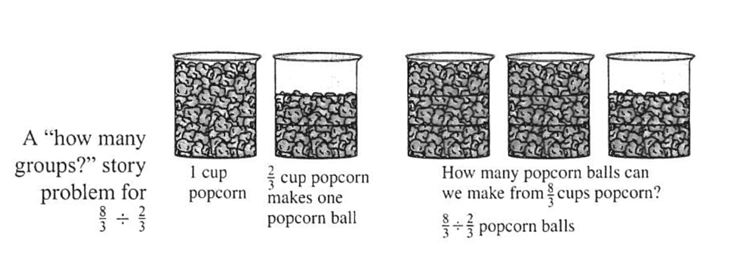

Good thing

that Sybilla Beckmann (author of a textbook to which we gave a high score, Mathematics for Elementary Teachers with

Activities, 4th ed.) wasn’t paying attention to that conclusion. She

provides three pages of discussion demonstrating both types of situation

described above, with no fewer than four explanatory graphics—exactly the types

of graphics elementary teachers can use in their own instruction.

Here’s one

of the graphics (and

the full discussion can be found here):

The quality

of textbooks in both elementary math and early reading prep vary dramatically.

Since our first reports on the preparation of elementary teachers in math

and reading, we’ve invested a lot in textbook reviews (analyzing the several

dozen elementary math textbooks and close to 1,000 early reading textbooks).

Ratings are based on extensive textbook reviews done by experts; in the case of

math textbooks, reviews are done by mathematicians well versed in the art of

teaching mathematically-skittish elementary teacher candidates. We’ve posted

both the math

and reading textbook reviews; doing more to ensure that teacher prep

instructors hear about these evaluations the next time they choose a textbook

for their course is critical.

More like this

Professional development that delivers: discovering the keys to better math and science outcomes

STEM teacher access: heading in the right direction, with a long way to go

OK, Boomer: Why younger generations may be more effective teachers