introduction

Strong preparation requires meaningful practice.

For many students, school this year looks very different from the way it did in the past. The COVID pandemic has meant that large numbers of students are learning by Zoom instead of in classrooms, and schools are struggling to reach students who don't have sufficient access to the internet or computers. In all this disruption, there is still one constant: the importance of effective, skilled teachers. Especially for students who may already be struggling, their teacher will be the difference between continuing to learn this year and falling even further behind.

While teachers continue to learn and grow as they gain experience, the foundation for their skills is provided by their initial teacher education program. And of all the parts of teacher education, none is more important than clinical practice. In general, the field of education has long recognized and championed the importance of practice. A 2010 blue ribbon panel organized by the profession's accrediting body called on the field of education to see clinical experiences as the core of teacher preparation1. In response, many programs have since increased the amount of their clinical practice, often, for example, switching from a semester-long to year-long student teaching. While length has become less of an issue (with the notable exception of alternative route programs), a large number of programs still have room to improve the quality of their clinical experiences.

The two standards addressed in this brief take different, but complementary approaches to better understanding the quality of clinical practice: the Clinical Practice standard addresses three elements of clinical practice that have an outsized effect on its overall value, while the Classroom Management standard takes a closer look at how teacher candidates practice a key instructional skill.

Unfortunately, there has not been much progress on the Clinical Practice standard in the seven years since the Teacher Prep Review began, owing largely to a lack of agency on the part of teacher preparation programs over the all-important selection of the mentor teacher. More on that problem follows.

There is better news to report when it comes to what teacher candidates learn about classroom management in the course of their training. The number of programs emphasizing all, or nearly all, of the most effective and universal classroom management strategies in clinical practice has increased by more than 26%. Two states' education agencies have led the way by implementing standardized student teaching evaluations with a focus on these strategies.

Have questions?

Review the glossary2020 National Findings

Clinical Practice

All aspiring teachers benefit from the firsthand experience of observing effective teachers at work and practicing under their direction. The challenge for teacher preparation programs is not only to provide teacher candidates with enough practice, but also to ensure that the practice, regardless of length, is a high-quality experience.

The evidence for the importance of high-quality clinical experience is undeniable. A 2010 National Research Council report said that clinical experience is one of three "aspects of preparation that have the highest potential for effects on outcomes for students."2 Remarkably, Daniel Goldhaber and his colleagues at the University of Washington reported in 2019 that first-year teachers can be as effective as typical third-year teachers if they spent their student teaching experience in the classrooms of highly effective teachers.3

First-year teachers can be as effective as typical third-year teachers if those new teachers spent their student teaching experience in the classroom of a highly effective teacher.

Although there are many other elements that contribute to what was once referred to as student teaching but is now often referred to as clinical practice, NCTQ's Clinical Practice standard looks for three essential components of quality:

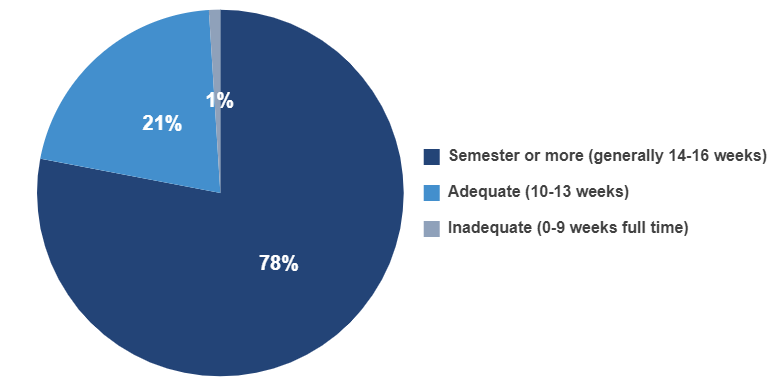

The practice occurs over a period of at least ten weeks and takes place for most or all of the school day. (Alternative route programs do not include this component and therefore are unable to qualify for a high score on this standard).

A supervisor from the program observes a candidate at least four times during the semester (or the latter half of the year, if it is a full year), providing written feedback with each observation. In alternative route programs where participants work almost immediately as the teacher of record, supervisors need to observe these novices just as often.

When assigning teacher candidates to classrooms, the program has a role in the selection of the mentor teacher, ensuring that the mentor teacher has the skills needed to mentor another adult and to be an effective instructor, as measured by student learning.

See the detailed methodology for the NCTQ Clinical Practice standard

Review the standardKey findings

1

The quality of clinical practice opportunities remains a problem of deep concern for the future health of the profession.

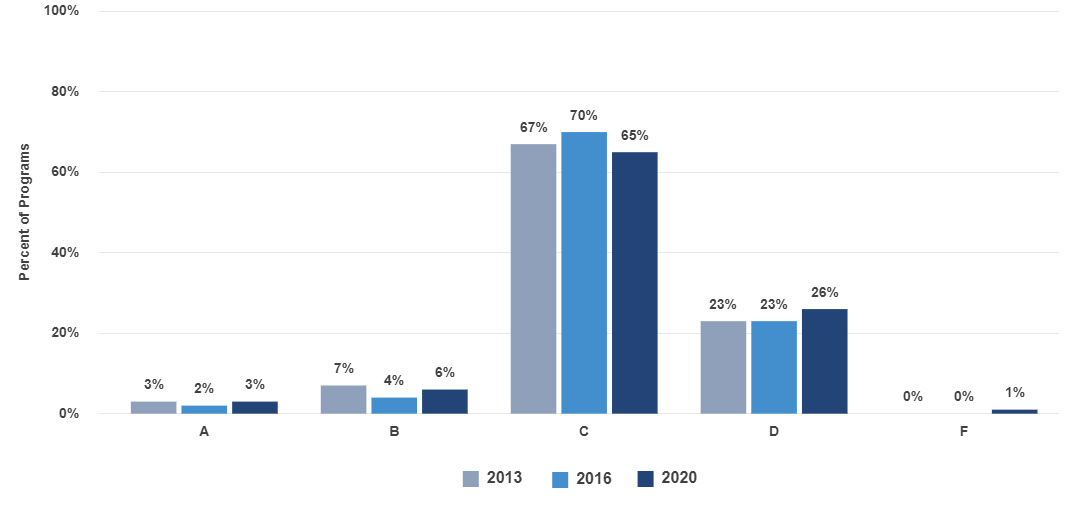

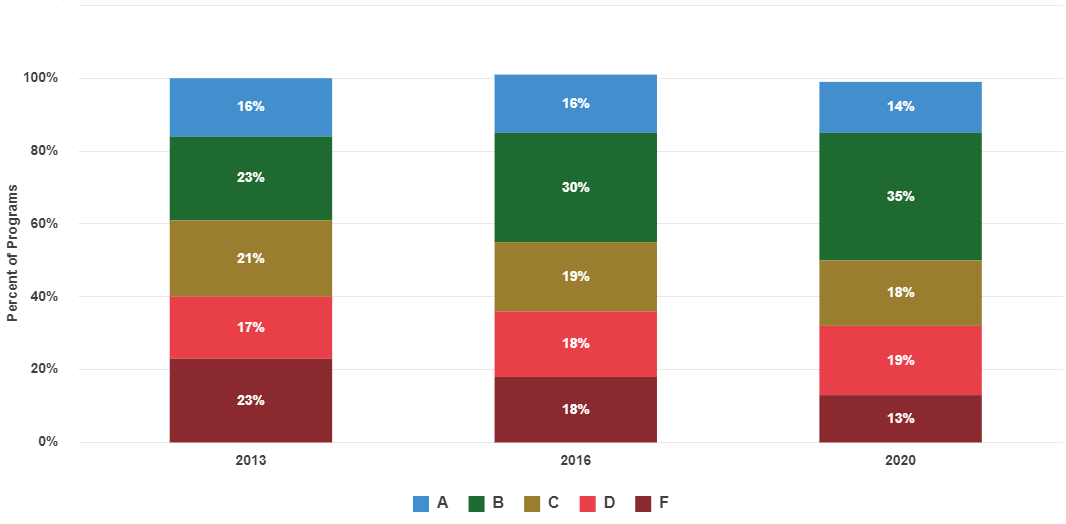

Clinical Practice Grades in All Editions of the TPR (Traditional Programs)

Grades summarize program performance on the three indicators (length, supervisory visits, and selection of the mentor teacher), and have been adjusted to reflect changes in scoring between 2013 and 2020. This data does not include alternative certification programs. Figures may not add to 100% due to rounding.

In 2020, most traditional programs still earn a C, showing no signs of progress since 2013. Typically, these programs provide at least ten weeks of clinical practice and require supervisors to provide adequate feedback, but they seldom insist that the mentor teachers chosen by the school district meet essential criteria.

2

Programs and their partner school districts are not working hand in hand to select great mentors, the factor most likely to determine the quality of the experience.

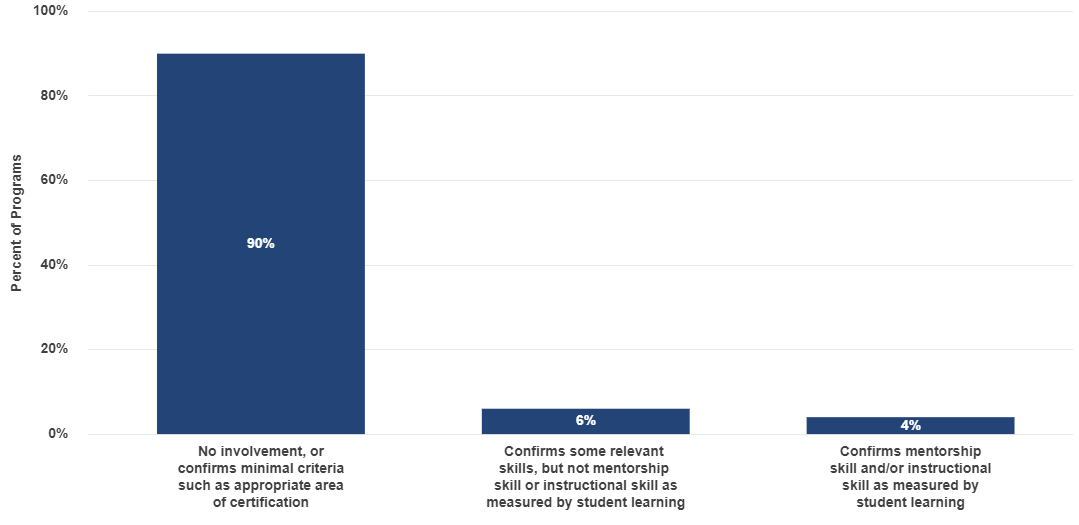

Program Role in Screening Mentor Teachers (Traditional Programs)

A strong mentor teacher can have an outsized influence on a teacher candidate's growth during clinical practice. However, while mentor teacher selection should be a cooperative process involving both the teacher preparation program and the placement school, currently only 4% of traditional programs appear to take much of a role in deciding who mentors the teacher candidate, no more than in 2013 when programs were first assessed on this standard. Instead, most programs send schools a list of student teachers who need mentors and accept the teachers that the schools propose. The one exception is that programs will sometimes push back with their school partners when they have had a poor experience in the past with a teacher.

Many programs report that they are not in a position to increase their involvement in the mentor selection process, because mentor selection has traditionally been the responsibility of the placement schools and because it can be hard to find teachers who are willing to serve as mentors. They are not wrong. Unfortunately, without active oversight by both programs and absent the school district appreciating the critical importance of clinical practice in securing a high quality workforce, mentor teachers are often selected simply because they volunteer.

3

A bright spot is supervision. Most traditional programs (71%) are providing a sufficient number of observations by a supervisor.

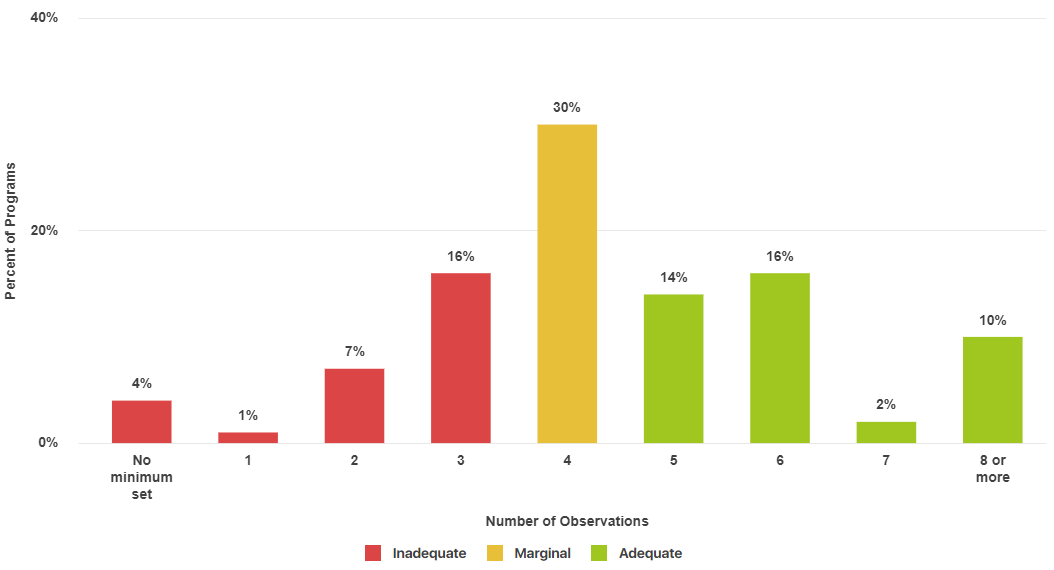

Supervisor Observations (Traditional Programs)

4

Almost all traditional programs include at least a semester of clinical practice.

Length of Student Teaching (Traditional Programs)

5

Alternative programs and residencies screen mentor teachers more carefully than traditional programs.

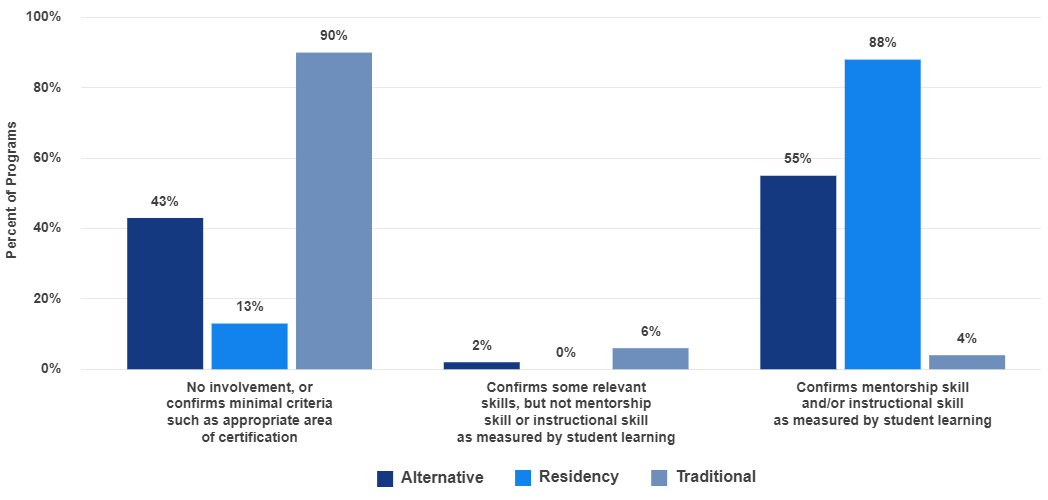

Program Role in Screening Mentor Teachers

(Traditional and Non-Traditional Programs)

The vast majority of elementary certification programs are university-based programs offering traditional student teaching. However, NCTQ also evaluated 59 non-traditional programs on the Clinical Practice standard. Residencies, which incorporate a year-long experience in a mentor teacher's classroom, tend to perform well on all three aspects of the Clinical Practice standard, including setting high standards for their mentor teachers. Non-residency based, alternative route programs also are more likely to identify high-quality mentor teachers than their traditional counterparts. Where these programs struggle is in providing enough time for clinical practice. Only a handful of the alternative route programs in this analysis offer practice in a mentor's classroom, with those experiences typically lasting four to six weeks. Because mentors in other alternative programs generally do not share a classroom with their mentees (instead only visiting from time to time) opportunities for guidance are limited.

Exemplary Programs in Clinical Practice

Forty elementary certification programs, including 33 university-based and seven residency programs, earned an A on this standard in 2020 because they incorporate the three essential components of effective clinical practice. Programs marked as "Consistently High Performers" received an A in every edition of the TPR in which they appeared. In addition, 16 programs below stand out because they improved their scores on the Clinical Practice Standard from a F in the edition of the TPR when they were first evaluated to an A in 2020.

2020 National Findings

Classroom Management

The environment in which students learn can have a major impact on their success. One study showed that students can learn 20% more when their teachers have the skills to create a positive environment.4 In order for new teachers to be ready to use these skills, it is essential to practice them, because classroom management can't be learned on paper. Student teaching, and other forms of clinical practice, are key times for this type of practice.

The Classroom Management standard looks at whether programs use observation and evaluation instruments during clinical practice that evaluate teacher candidates on five classroom management strategies supported by strong research, including a 2008 meta-analysis from the U.S. Department of Education's Institute for Education Sciences.5 These five strategies (when deployed correctly) have conclusive positive effects on students' behavior, regardless of their age, and together form a coherent approach to classroom management:

Establishing rules and routines that set expectations for behavior;

Maximizing learning time by managing time, class materials and the physical setup of the classroom, and by promoting student engagement;

Reinforcing positive behavior by using specific, meaningful praise and other forms of positive reinforcement;

Redirecting off-task behavior through unobtrusive means that do not interrupt instruction and that prevent and manage such behavior, and;

Addressing serious misbehavior with consistent, respectful and appropriate consequences.

See the detailed methodology for the NCTQ Classroom Management Standard

Review the standardKey findings

1

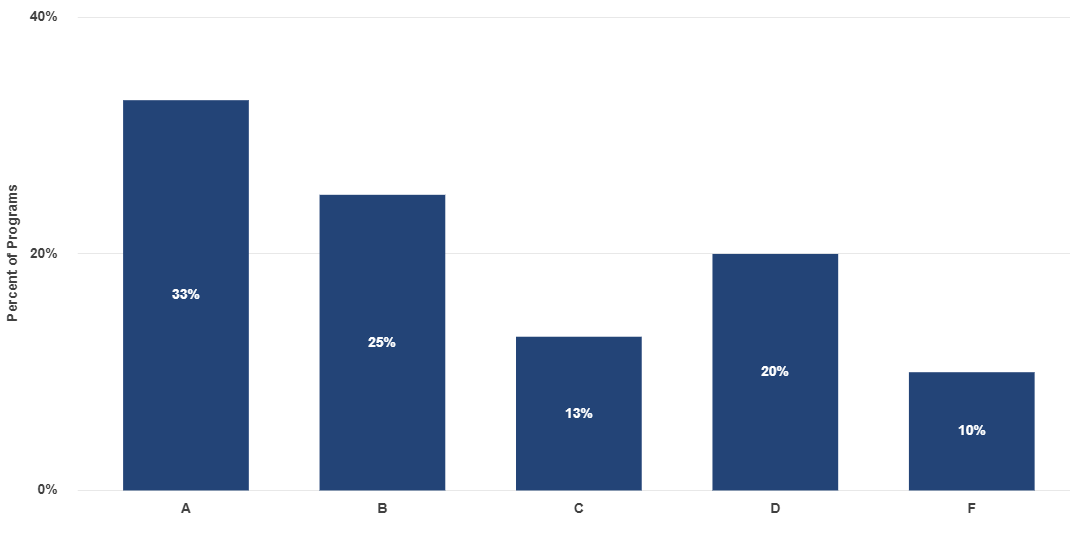

There has been a sizable 26% increase in the number of programs looking to research-based approaches to classroom management.

The Shift to Evidence-Based Classroom Management Strategies (Traditional Programs)

This data does not include alternative certification programs. Percentages may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

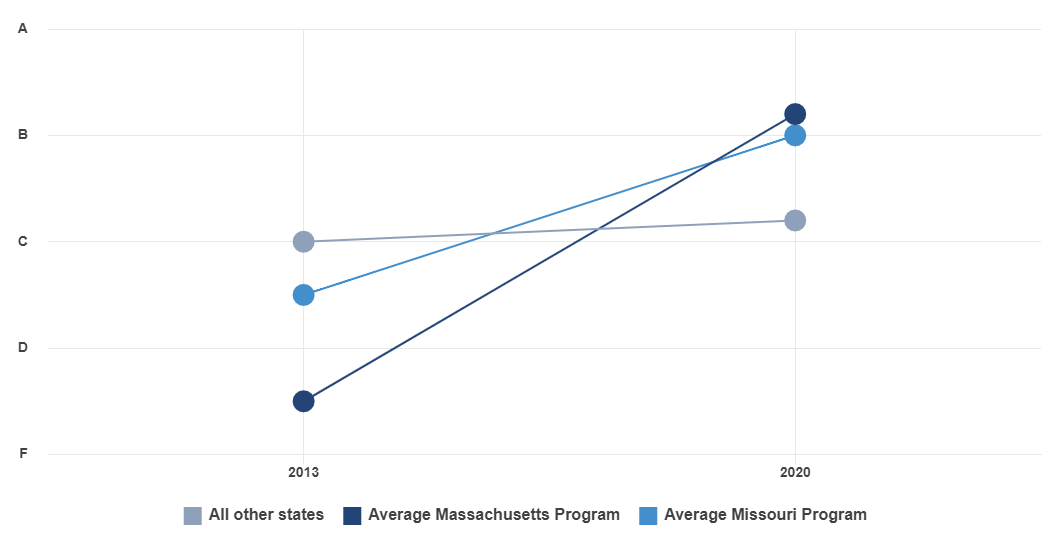

Programs that earn an A require candidates to demonstrate their ability to all five classroom management strategies during student teaching, residency, or equivalent clinical practice. At the other end of the spectrum are programs earning an F that require candidates to model at most one of the five strategies. Scores shown above for 2013 and 2016 are adjusted to reflect small differences between the current scoring system and the system used in earlier editions of the TPR.

2

One classroom management strategy, reinforcing good behavior with praise, still stands out as the least likely to be taught and practiced by traditional programs—even though it has the most research behind its efficacy.

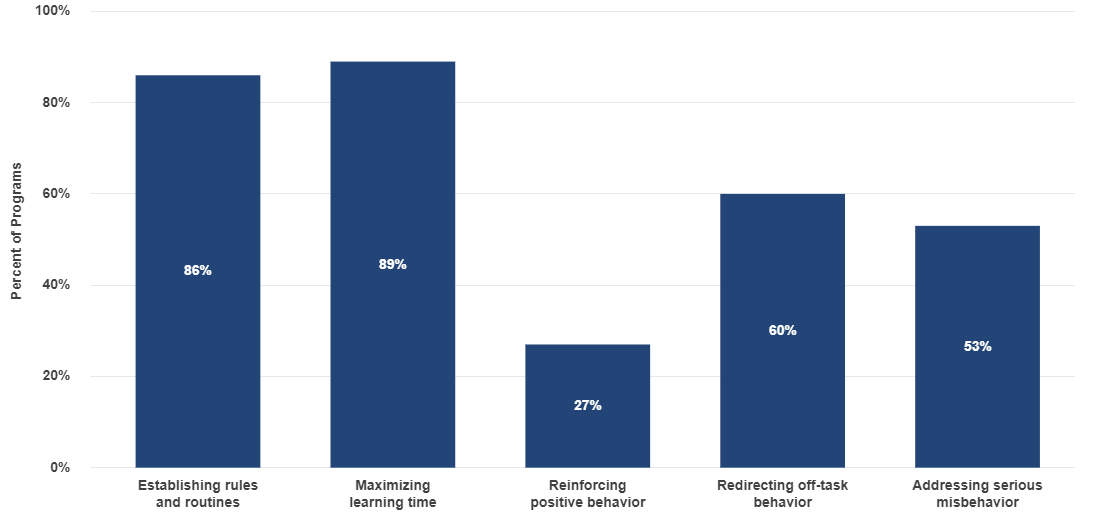

Program Adherence to Specific Classroom Management Strategies

(Traditional Programs)

The graph above shows the percentage of programs that mandate practice and feedback on each strategy during clinical practice. This data does not include alternative certification programs. Percentages may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

Praising students for positive behavior has been shown to be a powerful tool, yet only a quarter of programs require it to be modeled. The state of Missouri, a leader in this space, opted not to include this strategy in its otherwise strong evaluation instrument mandated for use in the observation of teacher candidates. This lack of emphasis on praise may be a result of concerns that praise will reduce students' self-motivation to learn. However, research shows that when praise is used well it not only improves student behavior but it also increases student's self-motivation.

According to the psychologist Daniel Willingham, the most effective praise causes children to change their own beliefs about themselves.6 A student who struggles to maintain focus in class, for example, may feel he is destined to fail and may stop trying to do well in school. However, if the student's teacher is able to offer sincere praise for sustained effort on a project, the student will feel that he is capable of succeeding in school and that his effort is worthwhile. Similarly, the work of Carol Dweck demonstrates that praising students for effort, not ability, can contribute to students' beliefs that their effort will result in success, resulting in an increase in students' motivation and resilience.7

In contrast, when students are praised effusively for something they already can do or that represents less than their best effort, they do not gain the benefits of praise.8 At worst, excessive, unearned praise may feel like a kind of consolation prize, and students who receive it may think that their teacher doesn't believe they can improve, and internalize this belief. However, praise for behavior can be tremendously effective when teachers hold high expectations for their students and only praise exceptional acts.

In short, effective praise is highly specific, focuses on the student's actions, and targets a behavior that the student is in the process of improving.

3

In spite of progress, many observation instruments popular with programs do not incorporate key evidence-based classroom management strategies. Only one, the National Institute for Excellence in Teaching (NIET) TAP instrument, is comprehensive and up-to-date.

| Essential classroom management strategies | CPAST | CAP (Massachusetts) | MEES (Missouri) | Danielson Framework | PDE 430 (Pennsylvania) | NIET TAP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standards of behavior | ||||||

| Learning time | ||||||

| Positive reinforcement | ||||||

| Redirect off-task behavior | ||||||

| Serious misbehavior | ||||||

| % of programs using | 2% | 3% | 3% | >20% | 7% | 4% |

Together, these instruments are used by 40% of all teacher preparation programs, with Danielson's Framework remaining the most popular, despite lacking three of the five strategies. The remaining 60% of programs typically use instruments designed by their own faculty. Encouraged by requirements of CAEP and state accreditors, many programs are starting to discard 'home-grown' evaluation systems to shift to validated instruments, but as this chart illustrates, the shift does not necessarily mean that programs will adopt an instrument which is comprehensive in its approach.

4

States can leverage their oversight of approved programs to set the right course.

Since the Teacher Prep Review began in 2013, both Massachusetts and Missouri have implemented required evaluation instruments, each of which require the teacher candidate to model four of the five essential classroom management strategies—with the result that all programs in the state qualified for no less than a grade of B. (Massachusetts did not include the strategy addressing serious misbehavior and Missouri omitted the reinforcement of positive behavior.) No other state saw this kind of large, systematic improvement among their programs in classroom management practice.

Unfortunately, because the Missouri and Massachusetts evaluation systems each omit one of the five classroom management strategies, teacher candidates at seven programs in the two states, now mandated to use this instrument, have lost the "A" grade status they earned in the 2016 Teacher Prep Review.

5

Non-traditional programs may be more likely to teach empirically-supported classroom management strategies.

Classroom Management Grades (Non-Traditional Programs)

Percentages may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

Because most elementary teacher prep programs are traditional, university-based programs which include student teaching, the Teacher Prep Review only includes a small sample of 59 non-traditional elementary programs. Of the graded programs on this standard, most (58%) ensured that participants learned about and practiced all or nearly all of the five essential classroom management strategies.

Exemplary Programs in Classroom Management

One hundred fifty-one elementary certification programs earned an A on this standard by ensuring that their teacher candidates practice all five essential classroom management strategies during clinical practice. Programs marked as "Consistently High Performers" received an A in every edition of the TPR in which they appeared. In addition, 38 traditional programs below stand out because they improved their scores on the Classroom Management standard from an F in the edition of the TPR when they were first evaluated to an A in 2020.

Recommendations

1

Educator programs and K-12 school partners should form meaningful clinical practice partnerships and work together to improve clinical experiences.

The benefits are clear: Improving clinical practice can lead to a stronger pool of future teachers and build mutually beneficial relationships between school districts and teacher preparation programs. For K-12 schools, upgrading student teaching can be a clear path to improving the teacher pipeline. For teacher preparation programs, ongoing communication about clinical practice can lead to better integration of the district's culture and the program's goals for its candidates.

School districts are in the best position to catalyze this process. They can get the ball rolling by:

Setting up regular meetings with teacher preparation programs to discuss goals and share data.

Tracking key data related to student teachers, including placement, hiring, performance, and retention.

Matching student teachers with specially selected cooperating teachers who believe that the school district is a great place to work (they are the front-line recruiters!); are passionate about developing aspiring teachers; are effective at teaching students, and are talented in instructional coaching and mentorship.

Placing student teachers in well-run schools, particularly schools which are educating high percentages of nonwhite students and/or are high poverty schools.

Providing stipend and scholarship opportunities for selected student teachers as well as their mentors.

Giving student teachers priority consideration for a full time job the following year, as long as their performance is acceptable.

Fulton County, GA shows how school districts can increase the value of student teaching as both a training opportunity and as a pathway to hiring great teachers. Fulton County created the First STEP internship program, in which student teachers are matched with the very best classroom teachers for a year-long experience in county schools. Student teachers, who are carefully screened, are attracted by a $3,000 stipend and guaranteed early consideration for jobs. Classroom teachers must show strong mentorship, instructional, and classroom management skills to be considered as mentors. Fulton County describes the First STEP program as enriching its teacher pipeline by attracting the best student teachers, supporting them, and raising the likelihood of their being hired by Fulton County once they are certified.

In future iterations of this standard, there will be more formal acknowledgment and measurement of the role that partner schools must play in securing a high quality practice teaching experience.

2

To strengthen clinical experiences, educator prep programs should place an emphasis on selecting strong mentor teachers.

High-performing educator prep programs shared the tools they use to ensure that mentor teachers have critical skills, such as being strong instructors themselves who also possess the fundamental knowledge of how to deliver effective support. Explore these resources below.

Exemplar Resources in Clinical Practice

3

To strengthen training in classroom management, programs should adopt observation and evaluation forms that provide comprehensive feedback to their student teachers.

The evaluation systems highlighted below demonstrate different ways that programs can provide high-quality feedback on all five essential classroom management strategies.

Conclusion

It is encouraging to see that progress has been made in the last seven years in the teaching of classroom management. However, the lack of corresponding change in other parts of clinical practice is concerning. The fact that many students will have difficulty learning during the COVID pandemic makes it even more important to ensure that their future teachers are well-prepared.

Teacher prep programs can improve their candidate's classroom management skills by choosing to use evaluation systems that incorporate research-based strategies on classroom management; many of the most commonly used instruments do not.

Most programs, however, cannot raise the quality of their student teaching placements on their own. Districts need to see student teaching as the key to improving their own teacher pipeline, and act accordingly. By taking measures to attract talented student teachers, and matching them with the very best mentor teachers, districts can substantially improve their pool of future hires.

Glossary

Clinical practice: Includes student teaching, residency, and, for alternative programs, the first semester of being a teacher of record.

Student teaching: An extended experience in a mentor teacher's classroom during which a teacher candidate either experiences all of the responsibilities of a classroom teacher, including responsibility for instruction of the whole class for a week or more, or has significant co-teaching responsibilities. Student teaching generally lasts for a semester or longer.

Traditional programs: University-based teacher education programs which incorporate student teaching and often lead to a bachelor's or master's degree.

Alternative programs: Programs in which participants quickly become teachers of record and do not experience traditional student teaching. These programs may be offered by universities or other types of providers.

Residency: Programs incorporating a year-long internship in a mentor teachers's classroom. These programs are offered by universities as well as other types of providers, and participants already have a bachelor's degree when the program begins.

Endnotes

National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education (NCATE). (2010). Transforming teacher education through clinical practice: Report of the blue ribbon panel on clinical teacher preparation and partnerships for improved student learning.

National Research Council. (2010). Preparing teachers: Building evidence for sound policy. Report by the Committee on the study of teacher preparation programs in the United States. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press.

Goldhaber, D., Krieg, J., Naito, N., & Theobald, R. (2019). Making the most of student teaching: The importance of mentors and scope for change. Education Finance and Policy, 1-11.

Kopershoek, H., Harms, T., de Boer, H., van Kuijk, M. Doolaard, S. (2016). A meta-analysis of the effects of classroom management strategies and classroom management programs on students' academic, behavioral, emotional, and motivational outcomes. Review of Educational Research, 86(3), 643-680.

Epstein, M., Atkins, M., Cullinan, D., Kutash, K., & Weaver, R. (2008). Reducing behavior problems in the elementary school classroom: A practice guide (NCEE #2008-012). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.

Willingham, D. T. (2006). How praise can motivate—or stifle. American Educator, 29(4), 23-27.

Dweck, C. S. (2002). Messages that motivate: How praise molds students' beliefs, motivation, and performance (in surprising ways). In Aronson, J. (Ed.) Improving academic achievement: Impact of psychological factors on education. New York: Academic Press.

Deci, E. L., Koestner, R., & Ryan, R. M. (1999). A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 627-668.

Acknowledgments

NCTQ teacher preparation team

Graham Drake (Managing Director), Laura Pomerance (Director, University Relations), Christie Ellis, Amber Moorer

Analysts

Akinyele Cameron-Kamau, Christian Bentley, Jessica Bischoff, Nakia Brown, Maria Burke, Jess Castle, Rebecca Dukes, Jamie Ekatomatis, Cheri Farrior, Jennifer Dailey Grandberry, Christine Lincke, Michelle Linett, Karen Loeschner, Jeanette Maydan, Rosa Morris, Sakari Morvey, Ashley Nellis, Amanda Nolte, Ruth Oyeyemi, Michael Savoy, Rebecca Sichmeller, Winnie Tsang, Mariama Vinson, Alexandra Vogt, Karin Weber, Myrna Williams, Victoria Wimalarathna

NCTQ Leadership

Kate Walsh (President)

Board of Directors

Thomas Lasley (Chair), Clara Haskell Botstein, James Cibulka, Hannah Dietsch, Chester E. Finn, Jr., Ira Fishman, Bernadeia Johnson, Henry L. Johnson, Craig Kennedy, F. Mike Miles, Arthur Mills IV, Chris Nicastro, John L. Winn, Kate Walsh (ex officio)

Technical lead

Jeff Hale, EFA Solutions

Design team

Diego Beauroyre and Katy Hinz, Teal Media

Advocacy and Communications

Ashley Kincaid, Nicole Gerber, Samantha Jacobs

Project Funders

NCTQ receives all of its funding from foundations and private donors. We appreciate their generous support of the Teacher Prep Review.

Arthur & Toni Rembe Rock

Barr Foundation

Carnegie Corporation of New York

Chamberlin Family Foundation

Charles Cahn, Jr.

Finnegan Family Foundation

J.A. and Kathryn Albertson Family Foundation

Laura and John Arnold

Longfield Family Foundation

Rainwater Charitable Foundation

Searle Freedom Trust

Sid W. Richardson Foundation

Sidney A. Swensrud Foundation

The Achelis & Bodman Foundation

The Anschutz Foundation

The Boston Foundation

The Bruni Foundation

The Irene E. & George A. Davis Foundation

The James M. Cox Foundation

The Lynch Foundation

The Phil Hardin Foundation

The Sartain Lanier Family Foundation

The Winthrop Rockefeller Foundation

Trefler Foundation

Walker Foundation

Anonymous (6)