Best Books for New Teachers (Part II)

This second part of our book recommendations focuses on books that help teachers learn about how to teach students to read and books on the big picture–international comparisons and efforts to improve education generally.

The moral dilemma of reassigning great teachers: a bad move for schools under the gun?

A message from Kate Walsh

This is a grave time. As we try our best to weather this storm, we find ourselves asking a lot of questions that produce answers no more reliable than what we might expect from a Ouija board.

NCTQ Statement on Institute of Education Sciences (IES) Contracts

Digging Deeper: Which types of institutions achieve excellence and equity for aspiring teachers of color?

Colleges and universities must lead the way in achieving excellence and equity for aspiring teachers of color. This report digs deep into which teacher preparation programs excel at both outcomes, revealing that more than 80 institutions achieve both equity and excellence in their candidates’ performance on licensure tests. NCTQ examines trends in pass rates across institutions, and finds that any type of institution can help their aspiring teachers achieve success, whether public or private, selective or not. The report challenges policymakers and educational leaders to examine their own licensure test data and to use that information to transform teacher preparation into a pipeline that consistently delivers diverse, highly effective educators who can meet the needs of all students.

Are we setting up English learners for reading success?

Every year, countless English learning students pass through our education system without getting the help they need. And for each one, a teacher is left feeling frustrated, or confused, and may not even realize why.

Scrambling to hire teachers doesn’t have to be a recurring rat race

Filling those hard-to-staff teacher vacancies doesn’t have to be so hard. Making a few straightforward adjustments to compensation, incentives, and partnerships can change the game.

Ten maxims: What we’ve learned so far about how children learn to read by Dr. Reid Lyon

Together we can address the literacy crisis head-on, reversing historical patterns of inequity and changing the lives of millions of our children.

How many school districts offer paid parental leave?

A review of school districts’ parental leave policies and how these policies can help support and retain teachers

Six steps to hire a strong teacher workforce

Insights on what school districts can do to ensure every classroom is staffed with an effective teacher.

Student teaching and initial licensure in the times of coronavirus

States must now consider how these coronavirus-related closures are impacting student teaching and other licensure requirements.

Do Board certified teachers propel whole schools forward?

The right incentives can motivate a student to do homework, an employee to hit a quota, and even a child to finish her vegetables.

Silent Progress on Education

If you’re anything like me, you can’t help but grow really discouraged at what seems like a lack of progress toward improving public education. I’ll admit there are days when I just want to throw in the towel.

I keep noticing, though, that there is actually a substantial amount of good news about American education that never seems to get any traction in either traditional or social media. I also suspect education reformers are so accustomed to calling out the bad news in order to incite action that we fail to appreciate the importance of good news. I’ve

discussed this here previously, but feel the need to revisit as there’s been a spat of generally unheralded good news.

There is new clear evidence that we are making slow, gradual gains adding up to significant change. Though you almost had to read between the lines to appreciate the genuinely good news in a recent Department of Education report,

“The Status and Trends in the Education of Racial and Ethnic Groups,” good news it was, indisputably. It cited the following progress:

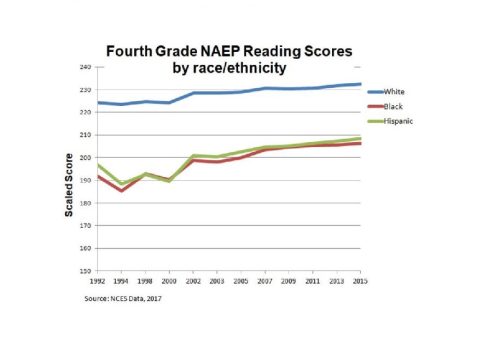

- Since 1992, on the fourth grade NAEP reading assessment, the White-Black score gap narrowed from 32 points to 26 points. This was not due to a drop in white scores, which went up by 8 points, but results from an even larger gain of 14 points among Black students.

- Similarly, on the eighth grade reading NAEP, the White-Hispanic gap closed significantly from 26 to 21 points. Again, Hispanic students made larger gains than did White students (12 points compared to 7 points).

- Since 1990, high school completion rates for young adults have gone up for all students, but most impressively for Hispanic students–increasing from 59 to 88 percent. Black students made great gains (from 83 to 92 percent), with both groups outpacing White student gains (from 90 to 95 percent).

- The number of bachelor degrees earned by Hispanic students doubled since 2004. It went up 46 percent for Black students.

From another source altogether, a

new report by Richard Whitmire for The 74/The Alumni found that some of the better-known charter organizations—including KIPP, Uncommon Schools, Achievement First, and YES Prep—are improving college graduation rates for poor kids by three to five times what our traditional public schools are doing. While charters aren’t NCTQ’s core issue—we’re agnostic about where kids find great teachers, just as long as they find them—I am hugely impressed by this result and extend my congratulations to the thousands of teachers who worked so hard to prepare their students for college.

Advocates of education improvement need to start calling attention to these success stories so that Americans understand that progress is being made and that decades of reform are showing results. Of course I’m not arguing that it’s time to declare victory and go home to rest on our laurels. We can all agree that America still has significant work ahead to raise the quality of the schooling provided to all students. And the media must share the blame as their bombardment of negative news buries the success stories. But we need to acknowledge reforms that work so we can learn from, replicate, and build on the gains they produce.

Because every day in the classroom counts

While I have many memories from my first year of teaching, one of the most visceral comes from my early morning commute. I had to take several buses across the Bronx to reach my school, always aiming to arrive well before my students. In the dead of winter, after too few hours of sleep, I’d wait for one bus while watching the one I’d just exited turn around – heading back toward my apartment. Some mornings, I needed all my willpower not to chase it down and go back to bed. But instead, I always continued my journey to school, and to the piles of work and (mostly) eager 7th graders awaiting me.

A new study shows that like me, other first-year teachers are quite good at consistently showing up to school rather than staying home. Ben Ost (University of Illinois at Chicago) and Jeffrey Schiman (Georgia Southern University) look at how the number of teachers’ absences (counting only sick and personal days, not professional development) change as their workload (e.g., class size, years of experience) changes.

While first-year teachers take few days off, teachers’ absences edge up for the next few years of teaching (at least based on the data from North Carolina). This trend toward more absences among more experienced teachers is notable because past research has found that teacher absences hurt student outcomes. In fact, this paper estimates that the gains in student learning attributed to having a more experienced teacher would be about 10 percent higher if those veteran teachers took fewer days off. This finding reaffirms that every day a teacher spends in the classroom is a critically important one.

While improving teacher attendance is no simple task, the North Carolina study sheds light on one potentially influential factor: school culture. Researchers found that when a teacher transferred from one school to another, her rate of absence crept toward the average for that school – for better or worse. (And yes, the authors took several steps to ensure that they weren’t simply capturing a “school-level shock” like a flu that hits everyone at the school.) Given that NCTQ’s past work on this issue, the 2014 Roll Call study, didn’t find any district policies that were silver bullets for improving teacher attendance, it seems that school-level factors may be a promising place on which to focus.

Preschool teacher prep: illusions of quality

30

million words. It’s a staggering number representing the tremendous gap in the

number of utterances (not distinct words) a child hears by age

four—depending on where his family falls on the socioeconomic spectrum.

Preschool

is regarded by many as the best opportunity for an early course correction,

allowing all children to be launched on a successful

academic—and life—trajectory no matter what is happening at home. Yet the jury

is still out on whether preschool can deliver on that promise. Research on the

long lasting contributions of preschool is at best mixed.

There’s

a lot of conjecture about why preschool investments may not

pay off as much as one might expect: the length of the preschool, parents’ involvement,

support services, low quality curricula, and poor oversight.

One

more plausible but largely ignored explanation remains: poor and/or

uneven preparation of preschool teachers.

While

preschool teachers’ dismally low salaries have garnered lots of attention, even this week, there’s

been little attention to the training given to preschool teachers before they

enter the classroom.

A new

NCTQ study to be released next week explores whether programs are

delivering essential content preschool teachers need. After all, beyond

being patient and caring, preschool teachers must be able to learn

and practice a wide swath of essential skills.

Put

more practically, when faced with the tremendous gaps in language skills in a

classroom of 20 four-year-olds, how many of us would have an inkling of where

to start?

Many

preschool advocates heavily champion the notion that all preschool teachers

must earn a bachelor’s degree in order to guarantee sufficient quality. Some 33

states now require that the preschool teachers in the programs they fund must

have bachelor’s degrees.

Though

there’s been little hard research to help guide that requirement, states made

what seemed like a safe bet, assuming that teachers who earn a bachelor’s

degree are more likely to learn how to create a higher quality preschool

environment than teachers who do not earn one.

Yet,

as it turned out, the assumption was just that, an assumption.

Our

new study out on June 22nd, Some Assembly Required, takes a

look at a healthy sample of 100 teacher preparation programs located in 29

states. The vast majority of these 100 programs conferred

degrees: 54 led to a bachelor’s degree and 41 to a master’s, as

well as 5 at the associate’s degree level. We looked at course

requirements, course descriptions, syllabi, student teaching handbooks,

observation instruments, and textbooks to identify high-level evidence of key

content.

A review of these multiple factors reveals that almost all of these programs fail

to reference even basic

content needed for a teacher to learn how to build children’s language, a

precursor to becoming a successful reader.

In many programs, the instructional skills specific to the

job of preschool teaching are marginalized, buried by other content only relevant to a teacher of later grades. Even on paper,

programs do not claim to devote much—or any—time to training candidates in

developing young children’s language skills and vocabulary or building critical literacy skills.

It’s

not just language and literacy that get short shrift. We found even less

evidence of programs attending to the knowledge preschool teachers need to

build math skills, explore early science concepts, or help children develop

executive functioning skills.

We’re

all for raising the bar for educators, especially those that play the crucially

important role of teaching young children. A bachelor’s degree makes

sense. But we need to make sure that the sheepskin earned by the preschool

teacher stands for something relevant and valuable.

Want

to learn more? Join the webinar next Wednesday, June

22.

Three reasons why every teacher prep program should adopt the edTPA…or not.

Over the last few decades, the field of teacher education

has heavily promoted the use and even the mandatory adoption by states of

standardized assessments that can be used to judge how well a teacher candidate

can deliver a lesson. The push has come with a promise that these

“TPAs” fulfill three important and otherwise largely elusive functions:

1.

They would help programs to better structure

training on how to plan and deliver instruction far better than the home-grown

efforts used by most programs.

2.

They identify the quality of candidates and

therefore can serve a gatekeeper for entry into the profession.

3.

They provide information which states could use

in the aggregate to hold programs accountable for their training.

We concluded four

years ago that the edTPA adequately fulfills the first function. TPAs are

an exponential improvement over the rubrics and observation forms most programs

use to assess a “live” lesson.

A new

study from three researchers at CALDER (Dan Goldhaber, James Cowan, and Roddy Theobald) provides evidence

on this second function—whether TPAs actually identify the more capable

candidates who deserve to be entrusted with a classroom of children. That’s long overdue given the pressure that

AACTE and others have put on states to adopt an instrument without any evidence

that it was predictive of teacher performance.

As was widely

reported in the press last week, results from graduates of teacher prep

programs in Washington state (one of the first states to adopt the edTPA) are

mixed. Goldhaber et al. found that a passing score in the reading portion of

the edTPA is significantly predictive of teacher effectiveness in reading, but

not in the math portion.

Given that the edTPA is a lot of work for programs and is

costly to boot, is this enough bang for the buck? After all, instructions for

candidates entail 40 pages and candidates are alerted that they can be

evaluated on the edTPA on nearly 700 different items. The process consumes the

attention of teacher candidates and teacher educators in their programs for a

good share of candidates’ semester-long student teaching placement.

There’s a strong argument that the complexity is merited if

it prevents unqualified persons from teaching—unless the same results could be

had with a lot less time and investment. A recent

study on the measures employed by District of Columbia Public Schools to

screen its teacher applicants indicates that one of the components with

predictive validity is simply a 10-minute audition. A few more studies with

similar results may make it difficult to justify blanketing the nation with edTPA

requirements.

That leaves the third function: program accountability. According

to Goldhaber, the variation of scores of candidates within Washington programs is greater than the variation of scores across programs. This result, which

Goldhaber did not publish, means that all but the most egregiously low performing

programs are likely to have candidates whose scores vary considerably across

the range.

The bottom line to date in this still-unfolding story about

TPAs: the edTPA 1) is a good organizing vehicle for training, 2) may produce

scores that at least partially discriminate among candidates in terms of

effectiveness—but through a process that appears to be unnecessarily

cumbersome, and 3) may produce scores that cannot be used to hold programs

accountable because they are insufficiently related to the quality of candidate training.

Teacher prep struggles gain global attention—and NCTQ’s at the table

A few weeks ago while my

blizzard-frenzied hometown of Baltimore was busy emptying grocery shelves of

bread and toilet paper, I took off for Paris—at the invitation of the OECD.

There’s nothing I love more than a great big snow storm, but sacrifices

must be made.

The occasion was OECD’s

kickoff event for a new study to look at how the world prepares its teachers.

Just as the U.S. had recently begun paying attention to the critical role

teacher preparation plays in teacher quality, so too has the international

community. (One of the first assignments I had when I arrived at NCTQ 13 years

ago was to participate in an OECD study on teacher quality. Exactly as

the teacher quality debate has played out in the U.S., virtually ignoring

teacher prep until recently, that study only identified the selection but not

the preparation of teachers as a factor of interest.)

My assigned role was to speak about US teacher preparation. It did

occur to me that If the OECD had consulted with American higher education

institutions or the AACTE about who would have been best to provide such a

perspective, my name would not have been on their list. And I will concede that

I did not paint a pretty picture, but it was a fair one backed up by the

evidence.

In fact, no country was there to boast, not even the largely Asian

PISA powerhouses. Finland’s delegate, for example, dismissed the notion

that only the top 10 percent of their college grads are admitted into teaching,

a myth he ascribed to the poorly understood fact that candidates are able to

apply multiple times and most, he asserted, eventually make it in.

Representatives from Hungary and Turkey expressed considerable dissatisfaction

with what they felt were their country’s excessive focus on teachers’ content

knowledge—and didn’t seem to notice me turning green with envy. Other nations,

particularly Australia and Chile, expressed problems eerily similar to ours.

I was also interested to hear that teacher bashing, however it

might be defined, appears to be a multi-national problem. Only South

Korea continues to report the high status of teaching as a chosen profession

while the rest of us bemoaned the profession’s ability to attract the best and

brightest. The most universal complaint? Without question, the deaf

ear on the part of higher ed to the practical needs of novice teachers.

In any case, the purpose of such a meeting is to fully air the

range of problems and organize them into manageable buckets, not come up with

the solutions. Actually, I’m not sure if a set of solutions should ever

be an expectation at any stage. The real challenge for any international

effort is the discipline and persistence required to descend from the clouds,

delivering comparative data at a level that is practical and concrete for the

countries involved. As I cannot recall more than a handful of such studies over

the last 20 years, that must be easier said than done. Most depend on

platitudes to fill their pages—not to mention a dizzying array of

incomprehensible flow charts (why does anyone think that converting a narrative

into a heavy mixture of text boxes and arrows somehow makes complex systems

more comprehensible?).

Solutions reside within each nation, perhaps spurred by education

ministries or groups such as ours (which appear to be increasingly prevalent, I

was heartened to see). We all benefit enormously from better

international data—not unlike the way that PISA results have helped the broader

education movement engage in better advocacy.

Many times over the

years NCTQ has reached out to education ministries and academics in other

countries with what we believe to be basic questions—such as “How many

schools of education do you have?” “What are the courses teacher

candidates take?” “What does it take to get in?” or “What

level of math proficiency does an elementary need to have?”—generally without

success. These are questions which are grounded in the nuts and bolts of

practice and which, if answered, might explain a lot. That’s how we learn

and improve. Not with generalizations or by

making assumptions about what works in other countries, but with facts and data

to back them up.

What teacher candidates won’t find in their textbooks

Over the holidays, I ran into an old colleague from back when I

was doing a lot of work in Baltimore during the 1990s. The conversation turned

to NCTQ’s work in teacher preparation. Perhaps half kidding, he accused me of

being a turncoat, referring to my newfound commitment to traditional teacher

preparation. “Whatever happened to you?” he launched in. “You

used to know that teacher prep was a total waste of time. Now you’re such a

booster!”

“Twenty-five years ago, that position may have made some

sense,” I retorted. “It’s just not a defensible position any

longer.”

What this guy didn’t realize—nor perhaps do a lot of people—is

that over the last couple of decades there’s been a boon in all sorts of

knowledge, much of it highly relevant to teaching. Unfortunately, little of

this knowledge has been integrated into teacher preparation. If it were,

we might see a big reduction in the all-too-steep learning curve experienced by

most novice teachers.

For starters, there’s the rock-solid science on how to teach

reading, which didn’t just end with the National Reading Panel in 2000, but has

continued to grow, particularly including the roles of oral language and

building broad content knowledge. There have also been advancements in basic

principles of instruction and managing human (e.g. classroom) behavior.

In a report NCTQ released yesterday, we again find

little evidence of these advancements making their way into mainstream teacher

education, specifically by means of the textbooks programs require for

coursework. This time, the field of study is human learning, our collective

knowledge of which, resting on a foundation laid over a century ago, has gone

into warp speed over the last few decades. And, we would contend, there is no

other subject that could benefit struggling new teachers more.

To determine the presence of this beneficial knowledge in

teacher prep programs, we analyzed the textbooks required in courses purporting

to teach how children learn (generally ed psych and methods courses), assessing

if any home in on the research-proven strategies that teachers can use to

help children learn as well as retain what they learn. Those very practical

strategies, some of which are supported by research going back decades, were neatly packaged and tied with a bow for an

audience of educators in 2007 by the Institute for Education Sciences, the

research arm of the U.S. Department of Education.

In an exhaustive analysis, our experts were not able to

identify a single textbook in our representative sample of 48 textbooks which

would be suitable for teaching this essential group of strategies. The majority

of texts adequately cover only a single strategy. None in the sample covers

more than two.

We wondered then if perhaps

programs worked around the deficiencies found in textbooks, supplementing them

with other resources. Looking for references to supplemental readings (hoping

one might be the IES guide itself), lecture topics and student assignments, we

found nothing. Further, since publishers generally only publish texts which are

likely to meet consumer demand, it seems unlikely that teacher educators are

clamoring for content they’re not getting. And the fact that the newly formed

Deans for Impact made the “science of learning” its opening salvo also suggests that this material

has yet to be embraced by mainstream teacher ed.

One explanation for the absence of these strategies from

textbooks and coursework is that the field of teacher education is more likely

to ignore research, not just because it sometimes comes from other fields, but

because it counters the prevailing views of teacher educators. That hypothesis

might explain why one of the six strategies (the one which also happens to be

backed up by the most science) receives such short shrift. That would be the “testing” strategy which

advises frequent quizzing to help students remember what they learn. Testing

is a dirty word these days. But it doesn’t explain the indifference on the part

of teacher education to the other strategies, such as teaching about the

importance of teachers distributing review or practice of new material across

weeks to promote retention of new material.

Another hypothesis might point to teacher education’s

unwillingness to put down its collective foot once and for all, rejecting much

of the current “research” which would more aptly be termed thought-pieces, non

generalizable case studies or small-sample investigation. That kind of culling,

by our estimation, would reduce the average ed psych textbook’s 2,200

references by about 90 percent—with most of the reduction due to the common

practice in these textbooks of citing a whole book as the supporting evidence

for this or that practice without even identifying the page number (imagine a

medical textbook accepting as adequate support a citation such as “Your Spine and You, 2000, Chicago:

Doubleday”).

The market for substandard textbooks has got to dry up. There

is simply no defense for using textbooks so untethered from the emerging

research about what works in practice. We look forward to working with

publishers and prep programs to ensure these books are pulled from the shelves.

See NCTQ’s latest report, Learning About Learning,

for a closer look at the research-proven instructional strategies teacher

textbooks leave out.